Mary Jane Beverly was born around 1846 in Anson County, North Carolina, a rural county dominated by large planters and merchants with little room for people like her parents, Lewis and Susan, to advance in life. Sometime between 1846 and 1848, the Beverly’s joined a tide of migrants who moved out from the Carolinas and into the lands once occupied by the Choctaw and Cherokee people. Migrants tended to settle near kin, like the famed Knights of Jones and Jasper County who came from South Carolina.[1] Mary’s family was no different, and when they settled outside of Demopolis in Marengo County, Alabama, there were nearly two dozen Beverly’s nearby.

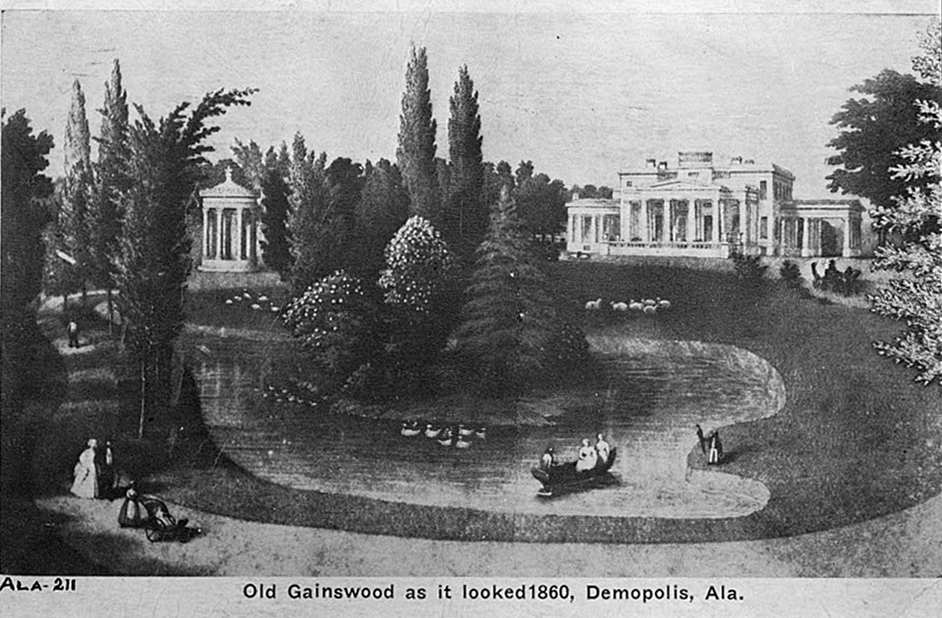

When they arrived in Demopolis in the late 1840s, the Beverly family would have found a bustling commercial river port set atop White Bluff overlooking the Tombigbee River. While many of Marengo County’s planter elite built mansions in the city, they never dominated it like they did in the Canebrake and the Black Belt. As a port town, Demopolis had a brisk nightlife and fluid social order fueled by itinerant laborers and travelers sojourning back and forth from Mobile on the river. “The People’s City” lived up to its name and offered working-class men like Mary’s father (a carpenter) the hope of carving out a niche for himself.

As promising as Demopolis was, the Beverlys continued their westward migration, perhaps compelled to flee Marengo County when Yellow Fever struck the area in 1853. By 1860, the Beverly’s were living in Lauderdale County, Mississippi, where Lewis was teaching his eldest son his trade, while his second son, John, tended to the family farm. Their mother, Sarah, ran the household business and tended to the four younger children, including fifteen-year-old Mary.

Lauderdale County was bustling on the eve of the Civil War. In 1850, Congress donated land to Alabama and Mississippi in order to build the Mobile & Ohio Railroad. The growing city of Marion, Mississippi—with its boys’ and girls’ academies, pharmacy, two blacksmith shops, six dry goods stores, and its Jacksonian newspaper (the Lauderdale Republican)—served as the county seat. But the owners of the M&O bypassed the city and built a station six miles to the south near a tavern called McLemore’s Old Field. This site would later grow to become the city of Meridian.

With the railroad came easier access to distant markets, which translated into more opportunities to make a fortune growing cotton. Lauderdale County land values increased 176 percent during the 1850s, leading many whites to purchase more slaves. By 1860, the county’s enslaved population had more than doubled, and local whites became vocal advocates of secessionism after Abraham Lincoln’s election as President.

Mary’s oldest brother was one of the first men in Lauderdale County to volunteer for service in the Confederate Army after the state seceded from the United States in January 1861. Oliver initially agreed to a one-year enlistment as a sergeant in the 13th Mississippi Volunteer Infantry Regiment, but he resigned and assumed the rank of Private ten days later. His first year in service was eventful, and he saw action at the battles of First Manassas, Ball’s Bluff, Savage Station, and Malvern Hill. Exhausted by constant campaigning, Oliver was medically discharged. Unwilling to abandon the fight for Confederate independence, he reenlisted in the 24th Mississippi Infantry in Shelbyville, Tennessee, on February 16, 1863. His second stint with the Army proved fatal, as he quickly contracted pneumonia and died the following April in Chattanooga. Oliver Beverly was twenty-three years old.

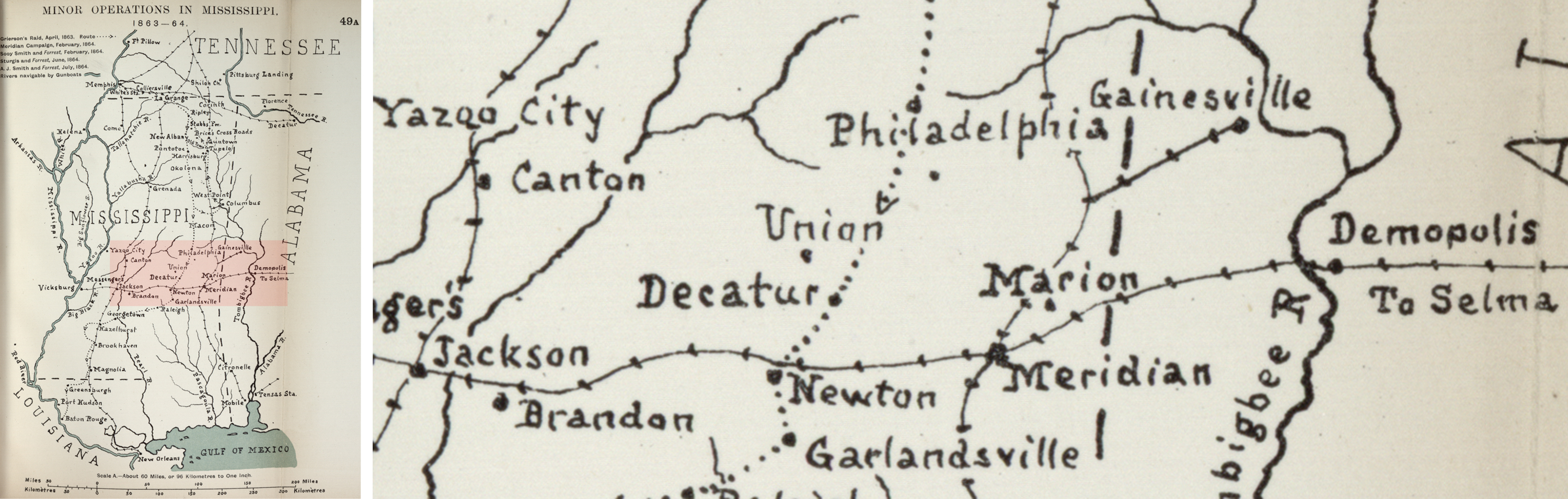

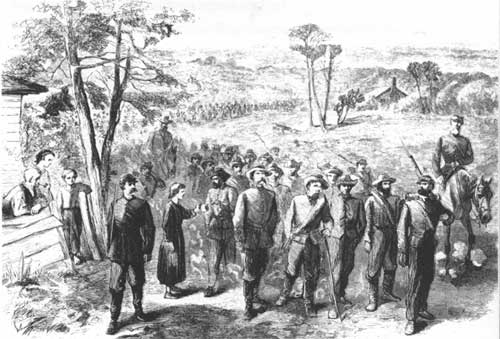

Conditions back home only worsened for the Beverly’s after Oliver’s death. In February 1864, the Union Army of the Tennessee under General William Tecumseh Sherman marched west across Mississippi from Vicksburg. On his way he captured and burned the state capital of Jackson before continuing on towards Lauderdale County and the railroad junction at Meridian. Sherman reached Meridian on Valentine’s Day and destroyed the railhead and Confederate arsenal located there. Two days later, he captured and raided nearby Marion as Confederate forces under General Leonidas Polk withdrew to Demopolis.

By the end of the campaign, Sherman’s army destroyed 115 miles of rail, sixty-one bridges, twenty locomotives, and three sawmills. It took the Union Army less than a month to destroy a decade’s worth of commercial development in Lauderdale County. Perhaps to the county’s credit, the railroads were back in operation only twenty-six days after their destruction. While Sherman failed to destroy the Confederate presence in eastern Mississippi, he had learned how to live off the land—a lesson that aided him greatly during his famous “March to the Sea.”

After the Civil War ended, Mary Beverly married a German immigrant and fellow Lauderdale resident named Jacob Ratzburg on March 20, 1866. Jacob was originally from Schleswig-Holstein, which was part of the Kingdom of Denmark when he was born in 1825. A carpenter like Mary’s father, Jacob arrived in the Port of New Orleans aboard the Washington in 1852. He then moved to Marion, Mississippi, and became a naturalized citizen of the United States in 1859. Prior to the Civil War, Jacob owned a forty-acre farm with his first wife, Louisa, and their daughter, Lorena. They also shared their home with Louisa’s sister and her husband, a fellow German expatriate named John Hamburg.

Jacob Ratzburg was 33 when the Civil War broke out, and he and his brother-in-law enlisted in the 8th Mississippi Volunteer Infantry Regiment in April 1861, fighting over the next three years at the battles of Murfreesboro, Chickamauga, and Chattanooga. He was eventually captured at the Battle of Jonesboro, where General Sherman outmaneuvered General John B. Hood’s army and captured Atlanta. We do not know what happened to Louise Ratzburg, but a woman claiming to be his daughter—a Mrs. R. L. Fowler—applied to have a Confederate headstone placed on Jacob’s gravesite in 1963. If this was his daughter Lorena, she would have been well over a hundred years old.

Nevertheless, Mary Beverly and Jacob Ratzburg were married in Lauderdale County after the Civil War. Mary, who was twenty years younger than her husband, gave birth to a son named John soon after the wedding. According to the 1870 U.S. Census, the Ratzburgs shared their home with three African-American farm laborers, including an eleven-year-old girl named Eda Ratzburg. The Ratzburgs remained on their farm, renting out rooms to hired hands and their families, and grooming John to take his father’s place.

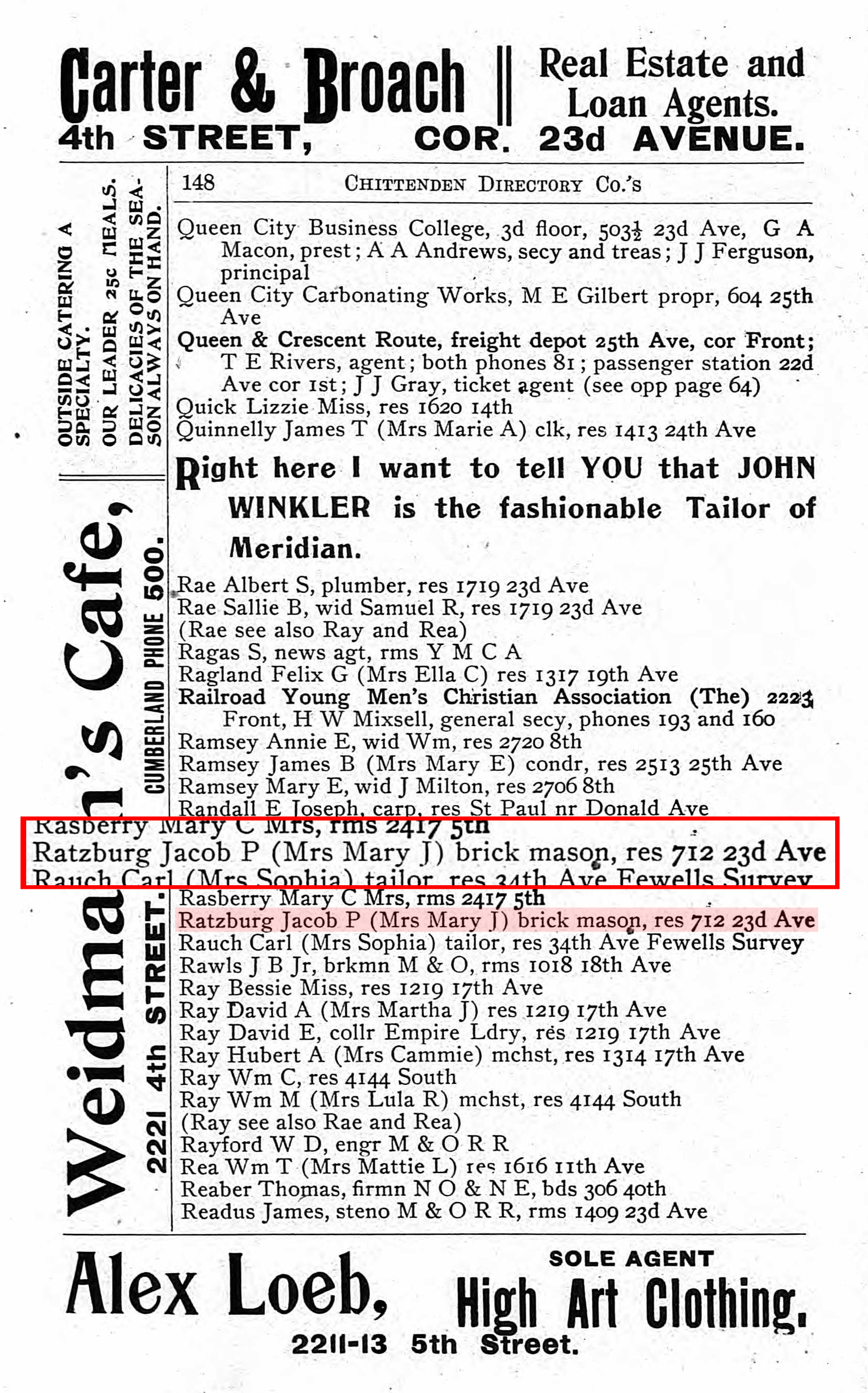

Sometime after 1890, Mary and Jacob lost their farm and moved to a rented house in Meridian. By 1900, Jacob (now 74) was working only six months out of the year as a brick mason and the couple took on boarders to supplement their income. Aging and struggling to make ends meet, Jacob applied for a pension from the state of Mississippi in 1904. In his application he claimed that he was living in a small home and did not have any “relations or connections whose legal or moral duty” it was to care for him and Mary. He could only point to a niece and nephew, and since there are no records pertaining to their son John after 1880, it is possible the young man had died.

The Ratzburgs moved to Beauvoir, which had opened fifteen months earlier, on March 23, 1905. The Ratzburgs lived there together until Jacob died two years later. Mary was only 61 years old then, and she remained at Beauvoir. In 1914, she married fellow resident J. N. Webb, a veteran from Marshall County who had fought with the 10th Mississippi Infantry Regiment, at the Methodist Church in Biloxi. Webb died in 1919, and five years later Mary married another Beauvoir resident, George W. Bazemore, a cavalryman from Lee County, Mississippi. Bazemore died in 1924. Now 78, Mary had been living at Beauvoir for nearly twenty years and outlived three husbands. She enjoyed another half a decade living by the sea until she passed away on August 15, 1929 at Beauvoir, where she is buried.

Lead author: Allan Branstiter, doctoral candidate in the Department of History, the University of Southern Mississippi. Research and analysis for this essay was conducted by University of Southern Mississippi undergraduate history majors Armendia Hulsey and Jonathan Davis, as well as doctoral candidate Allan Branstiter.

___________________

[1] Victorian Bynum’s book Free State of Jones addresses the Knights and the Carolinians who settled the land along the Alabama-Mississippi border.