One of the key factors that contributed to Beauvoir’s successful operations was the influence of the Tartt family. From 1916 through 1945, with the exception of only four years, Elnathan and Helen Tartt served as superintendent or assistant superintendent of the home. Their close supervision represented a New South bureaucratic efficiency that allowed for a constant level of care as well as key support from the state legislature and from the governor’s office.

Beauvoir Superintendents Elnathan and Helen Tartt, and their son Ned at Beauvoir. Either Elnathan or Helen Tartt served as superintendent of Beauvoir from 1916-1943 except for one four-year term from 1932-1936. Mississippi Gulf Coast Community College Beauvoir Collection.

Helen Tartt entered the role as assistant superintendent, to her husband Superintendent Elnathan Tartt, as early as 1916 (though she did not officially receive that title until 1920). In 1926, she accepted the governor’s appointment to run the home, a decade or more before it became common for white women to lead Confederate homes. Tartt reported to Beauvoir’s five-member all white board (which also included two women) and directly to Mississippi’s governor. They shared this role until 1928, when Elnathan Tartt resumed his role as superintendent and Helen as assistant superintendent. When political winds changed in the state in 1932, they were both replaced, but four years later, Helen Tartt resumed the leadership of Beauvoir, and she held the position of superintendent until her death in 1943.[1]

Throughout her leadership of the home, Helen Tartt managed large legislative appropriations and massive Depression-era cuts budgets with equal success. She directed the daily operations for as many as 250 residents and dozens of employees. She oversaw the physicians and hospital staff, the purchasing of food, livestock, and supplies, and managed all contract work for the property.[2] Her leadership came at a time of rising opportunity for white women in Mississippi. Women studied at institutions of higher education, entered the professional workforce, and assumed leadership roles at the state-funded women’s college, in the suffrage movement, in the arts and literature.[3]

On August 1, 1926, the New Orleans Times-Picayune featured Helen Tartt on its front-page coverage of leading white women in the region.

Helen Tartt’s early leadership may have been made possible by her husband’s success as a popular long-term superintendent, the experience she learned as assistant-superintendent to Elnathan, and his political connections to Governor Theodore Bilbo. Still, Helen gained recognition throughout the Gulf South, in her own right, for her advocacy of Beauvoir residents and the efficiency with which she ran the home.[4] The New Orleans Time-Picayune featured Tartt’s leadership of Beauvoir with a front-page article and photograph in 1926, insisting that it was a blend of her “good cheer, patience, housewifely and executive abilities” that “won for Mrs. Helen Tartt the only headship of a state institution in Mississippi.” The editor noted Elnathan’s prominence, but concluded that the board selected Helen “because of her eminent ability to handle this extremely difficult job.”[5] The public recognized Helen Tartt’s organizational acumen, too, if only through their regular contact with her as a prominent, influential business woman. From the late 1920s through the early 1940s, local papers printed frequent notices calling for bids from grocers, dairy farmers, undertakers, and contractors for services needed at the home, and readers were instructed to contact “Mrs. Helen Tartt, Supt.” with their sealed bids. These notices served as regular reminders, year after year, that a New South woman directed Beauvoir’s large-scale and efficiently run operations.[6]

Helen Tartt died in her leadership role at Beauvoir in April 1943. Elnathan accepted the role of superintendent for a short before resigning from the position later that summer.[7]

This post is excerpted from the

article by Susannah J. Ural, “‘Every

Comfort, Freedom and Liberty’:

A Case Study of Mississippi’s Confederate Home,” The Journal of the Civil War Era 9

(March 2019), 55-83.

[1] New Orleans Times-Picayune, August 1, 1926; Biloxi Daily Herald, April 2, 1943.

[2] Twelfth Biennial Report of the Board of Directors, Jefferson Davis Beauvoir Memorial Home, 1926-1927. Beauvoir, Soldiers Home Reports, Folder 1, Jefferson Davis Presidential Library, Biloxi, Mississippi.

[3] Marjorie Julian Spruill, “Nellie Nugent Somerville: Mississippi Reformer, Suffragist, and Politicians,” Joanne Varner Hawks, “Belle Kearney: Mississippi Gentlewoman and Slaveholder’s Daughter,” and Sarah Wilkerson-Freeman, “Pauline Van de Graaf Orr,” in Mississippi Women: Their Histories, Their Lives, eds. Martha H. Swain, Elizabeth Anne Payne, Marjorie Julian Spruill (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2010), 72.

[4] Praise for Elnathan Tartt, Helen Tartt, and the efficiency of the Jefferson Davis Soldiers’ Home appeared in dozens of papers from 1916 through the 1940s. Examples of this appear in the Daily Mississippi Clarion and Standard (Jackson, Mississippi), September 1, 1921; Biloxi Daily Herald (Biloxi, Mississippi), July 14, 1926; Greenwood Commonwealth (Greenwood, Mississippi), August 12, 1927; Indianola Enterprise (Indianola, Mississippi), September 29, 1927.

[5] New Orleans Times-Picayune, August 1, 1926.

[6] These ads appear regularly in the Biloxi Daily Herald from the late 1920s through the early 1940s. Specific examples can be found on May 14, 1927, July 3, 1936, and September 15, 1941. Thanks to Ward Calhoun, Carole Marshall, and Kathy Goss for their help in locating information on Helen Tartt.

[7] The Greenwood Commonwealth (Greenwood, Missisisppi), June 2, 1943.

]]>The Unusual Case of James Burney, Nathan Best, and Frank Childress

[This essay — revised for length — was taken from the article by Susannah J. Ural,

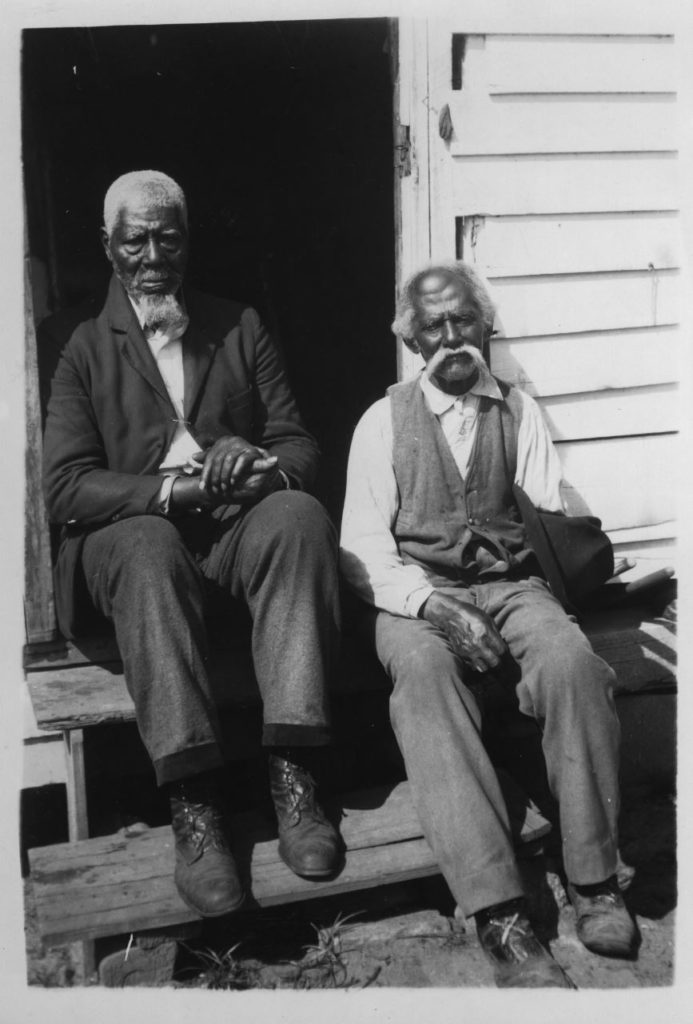

athan Best and Frank Childress, former Confederate body servants, Confederate pensioners, and residents of Beauvoir. Mississippi Gulf Coast Community College Dixie Press Collection

In the early 1930s, three aging, impoverished men entered the Jefferson Davis Soldiers’ Home in Biloxi, Mississippi. The facility, commonly known as Beauvoir, was Mississippi’s state home for destitute Confederate veterans and their wives or widows. Two of the men, Frank Childress and Nathan Best, bore clear signs of their wartime injuries. Childress suffered, he reported, from a “sore leg caused by a gunshot wound received during service in 1861.” Nathan Best’s empty sleeve spoke to his injury and amputation during the Petersburg Campaign. None of this made these men exceptional cases among Beauvoir residents except for one key factor. All three men — Childress, Best, and James Burney — had been enslaved Confederate body servants during the Civil War. This had made them eligible for a Mississippi Confederate pension funded by the state, and it also granted them access, or at the very least, consideration for access, to Beauvoir. They were also exceptional as the only African-American pensioners that the Beauvoir Veteran Project research team has been able to find living as residents (not employees) of a Confederate home.

Their admission was the result of an unusual pension policy that began in Mississippi in the late 1880s. When state legislators created the Mississippi’s Confederate pension policy in 1888, it provided modest financial support to Confederate veterans and their widows who had not remarried, as well as “the servants of the officers, soldiers and sailors of the late Confederate States of America, who enlisted from the State of Mississippi.”[1] It was not until the 1920s that five other states passed variations of this policy, joining Mississippi in providing pensions for formerly enslaved Confederate military “servants” or, in other states, laborers. Beyond being early, Mississippi’s policy was unique because legislators decided to pay African-American and white pensioners at the same rate. When Mississippi’s 1890 Constitution omitted reference to pensions for “servants,” state legislators took the time to clarify in 1896 that formerly enslaved men who had served Confederate soldiers could still receive state support. Legislators then took an even more unusual step in the Jim Crow South by insisting that veterans, widows, and “servants” would “share and share alike” from the state’s pension fund.[2]

They did this because in the eyes of white elites, many of whom were former slave owners, it allowed them to aid formerly enslaved men who had served the Confederate military effort in ways that whites saw as acceptable — as camp servants rather than as armed combatants.[3] Indeed, if Mississippi failed to do this, they fed the North’s narrative of the war. As one Mississippi editor explained, if Mississippi ignored such service, it “would mean that while negroes who rendered any military service for the Yankees are handsomely pensioned, those who served their masters in war adopted an evil policy and should be condemned.” Pensions for Confederate “servants” helped sustain the image of “loyal slaves” and similar aspects the Lost Cause memory of the war. [4] This argument swayed leading Mississippians until 1922, when a new generation rejected the idea of equal pensions regardless of race.[5] But this state endorsement was sufficient to warrant Frank Childress, James Burney, and Nathan Best the opportunity to apply for and gain admission as residents of Beauvoir.

In August 1930, a Harrison County pension board reviewed James Burney’s claim that he had served as Confederate President Jefferson Davis’s “

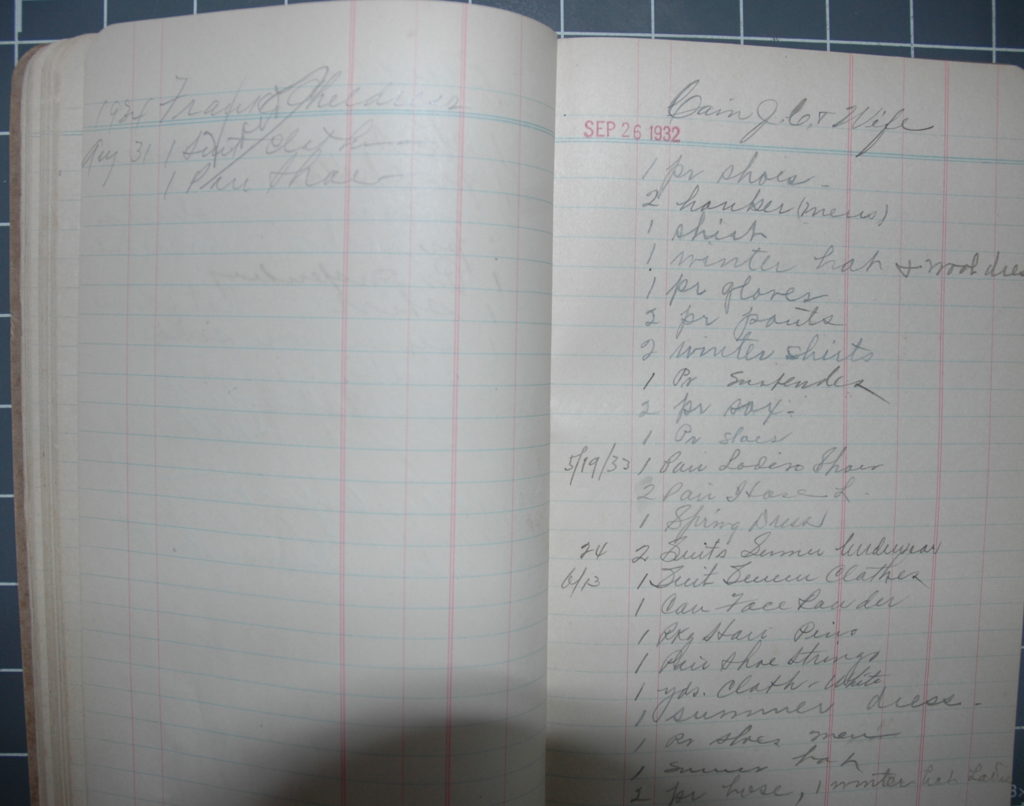

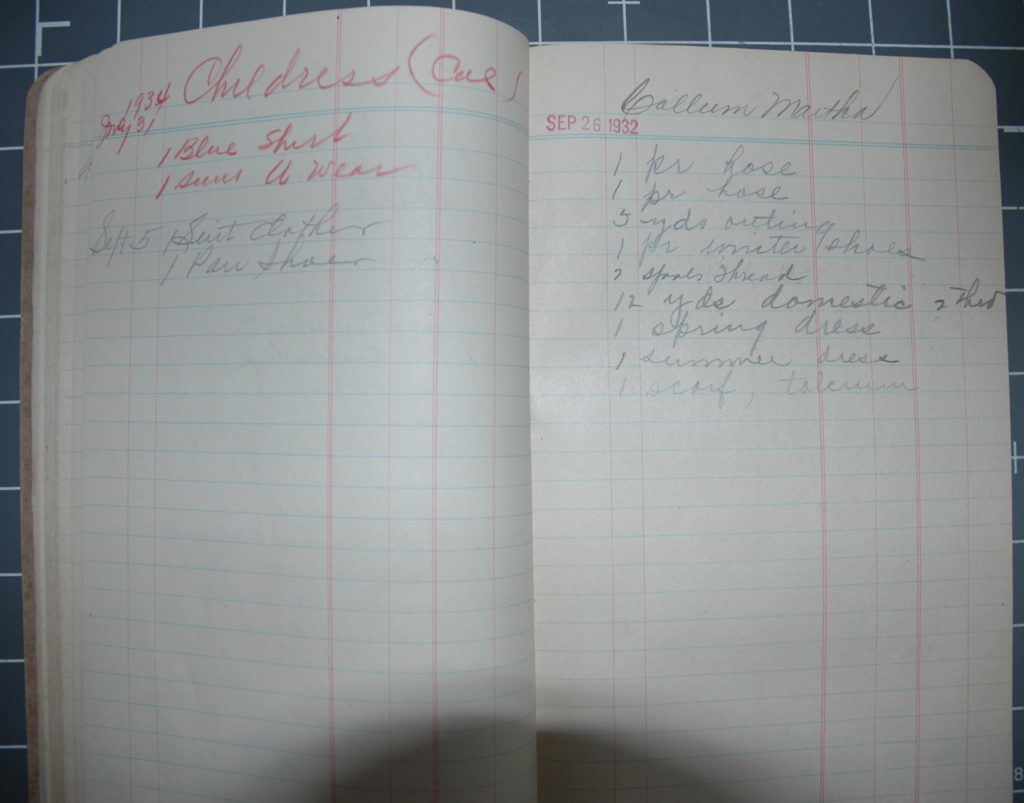

In August 1932, Frank Childress applied for a Confederate pension in Tunica County, Mississippi, where he explained that he had been a body servant to Colonel Mark Childress and suffered an 1861 gunshot wound to his leg. [insert image of Frank Childress pension app] The board approved his application in September 1932, but, like Burney, those funds, reduced on the grounds of race, were not sufficient to sustain Childress. He applied for residency at Beauvoir and arrived at the Jefferson Davis Soldiers’ Home in July 1934. A lack of sources prevents our knowing why Childress moved when he did, but he likely was motivated for the same reasons as many of the residents: at

Much more is known about the third African-American resident of Beauvoir, Nathan Best. [9] He entered the home with James Burney in August 1932, and later lived with Frank Childress. Childress and Best received the same $2 allowance as other residents, but their clothing allotment was less than that of white residents and their cabin was segregated from the cottage-like dormitories that housed white veterans, wives, and widows. Best explained, in the words of a 1930s Works Progress Administrative (WPA) interviewer, how he lived on this meager support: “I

Frank Childress clothing allotment. Beauvoir Ledger “Items Given to Inmates, 1932-1934” Housed at Jefferson Davis Presidential Library, Biloxi, Mississippi.

North Carolina-born Best was about sixteen years old when the Civil War began. He spent his youth enslaved in Snow Hill, North Carolina on the large Greene County plantation of Henry Best.[12] In 1863, Nathan Best went to war with his owner’s younger brother, Rufus Best. While carrying messages during the siege of Petersburg, Nathan Best’s horse fell and Best broke his arm so badly that it needed to be amputated. After the war Best returned to North Carolina where he worked as a farm laborer and married a freedwoman named Hester. He was an engaged voter and active in his community, but this enfranchisement ended abruptly when white North Carolinians “Redeemed” their state and the Klan threatened black North Carolinians who attempted to vote. The years after the war were good, he insisted, until then.[13]

Nathan Best worked in Greene County until 1880, when he and Hester and their three children moved to Wilson County, North Carolina, and then south to Georgia where Best worked in the turpentine industry, as he and his father had before the war. Hester died sometime before 1910, and Best married a woman named Nancy. By then the couple, and perhaps Best’s children, were living in Ocean Springs, Mississippi, a coastal town not far from Beauvoir, where Best made a living plowing small plots of land around town. Although neither could read or write, Nathan and Nancy Best owned their own home and clarified to the census enumerator in 1910 and again 1920 that they owned it mortgage free.[14] By the early 1930s an aging Nathan Best, now in his nineties and a widower — Nancy died in the 1920s — could not earn a sufficient living to sustain himself on a meager monthly pension.[15] He was admitted to Beauvoir and entered the home with James Burney on August 7, 1932.

Nathan Best and Frank Childress were featured in two newspaper and magazine accounts that emphasized their role as Confederate pensioners and residents, and they participated in ceremonies when prominent Americans — like Franklin Delano Roosevelt — visited Beauvoir. Writers highlighted Childress’s capture by Union forces and his admission that he later fought for the Union, but only because, the report claimed, he was forced to do so. A 1936 Mississippi Guide article included what was purported to be a direct quote from Childress himself: “

In a 1930s WPA interview conducted at Beauvoir, Nathan Best gave no indication of such dreams. When he talked about his life as a slave, he characterized his original owner, Henry Best and later his son, Bob, as “good” owners, but Best also described being hanged, whipped, and abused by an overseer on multiple occasions. If Best dreamed of anything in the future, it was leaving Beauvoir. While he liked things “pretty well here,” Best said he “would like it better ifn dey’d jes’ give me ‘nough pension, so I could live at home.”[17] It appears that Best got his wish in March 1939. He received an honorable discharge from Beauvoir and moved to his daughter’s home in Biloxi, and his Confederate pension benefits were reinstated one month later. Best died there in January 1940.[18]

Little

is known about the experiences of African-American residents of Confederate

homes. One scholar has argued that more black pensioners were admitted to

Southern homes as Confederate veterans died and the homes’ white populations

declined. It is not clear, however, that this practice extended beyond

Beauvoir.[19] In

1924, Kentucky’s Confederate home hired William Pete, a formerly enslaved Confederate

body servant, rather than admit him as a resident. The board felt compelled to

do something for Pete, who had been enslaved to Confederate General Joseph

Wheeler, but they refused to admit him as a resident.[20]

Mississippi chose another approach. Nathan Best, James Burney, and Frank Childress

were admitted to Beauvoir and received the same resident allowance, but they

received less clothing and lived in segregated quarters. Even in monthly

payment records and in the Jefferson Davis Soldiers’ Home Register, their names

appear at the back of the old bound volume.[21]

The public wrapped the men in the legend of the Lost Cause and blended their

wartime and postwar experiences into the myth of the happy slave. But James

Burney, Frank Childress, and Nathan Best — despite Klan violence, Jim Crow

bigotry, and reductions in their pensions — used a complicated Confederate

memory to secure shelter at Beauvoir when they had nowhere else to turn. Once there, they challenged residents’ and

visitors’ Confederate memories until Childress and Best’s families could help

them regain their independence with assistance from a Confederate pension.

Notes

[1] Journal of The Senate of the State of Mississippi at a Regular Session Thereof, Convened in the City of Jackson, January 3, 1888. (Jackson, MS: R. H. Henry, 1888), 333.

[2] Laws of the State of Mississippi Passed at Regular Session of the Mississippi Legislature Held in the City of Jackson, Commencing January 7, 1896, and Ending March 24, 1896 (Jackson, MS: Clarion-Ledger Company, 1896), 65; See also Foster, “‘To Mississippi, Alone,’” 34-37; Hollandsworth, Jr., “Looking For Bob,” 305; Dale Kretz, “Pensions and Protest: Former Slaves and the Reconstructed American State,” The Journal of the Civil War Era, 7: 3 (September 2017), 425-445.

[3] Mississippi only awarded pensions to formerly enslaved Confederate body servants. While some applicants referenced carrying dispatches or being wounded in pension applications, the state did not recognize them as combat soldiers. For a detailed analysis of this pension policy, see Hollandsworth “Looking For Bob.” For more on the Black Confederates debate, see Kevin Levin, “Myth of Black Confederates Won’t Go Away,” The Post and Courier (Charleston, South Carolina), October 11, 2017; Levin, “What Black Confederates Really Did During the Civil War” The Atlantic, February 21, 2012.

[4] The Lexington Progress Advertiser quoted in Jackson Daily News (Jackson, Mississippi), February 12, 1904; see a similar argument in Yazoo Herald (Yazoo, Mississippi), February 21, 1908.

[5] House Bill 382, Laws of the State of Mississippi Passed at Regular Session of the Mississippi Legislature Held in the City of Jackson, Commencing January 3, 1922, and Ending April 8, 1922 (Jackson, MS: Clarion-Ledger Company, 1896), 213-215. See examples of protest against this change see Natchez Democrat (Natchez, Mississippi), February 10, 1922 and February 14, 1922.

[6] Hollandsworth, “Looking for Bob,” 310-312.

[7] James Burney Pension Application, September 1, 1930 states that Burney worked for President Davis during the war as a body guard from April 4, 1863 through 1865. There is a letter supporting this claim from Sam Burney, for whom James Burney worked after the war. Burney’s August 1930 pension application makes the same claim. Beauvoir Veteran Project researchers investigated each resident in the sample to verify any reference to military service in the home register or in pension applications. To date no documenting evidence has been found in the Jefferson Davis papers or through inquiries to the National Civil War Museum to confirm or reject Burney’s testimony that he served as Jefferson Davis’s body guard. James Burney Pension Application, Harrison County, Mississippi. Mississippi Office of the State Auditor, Series 1201: Confederate Pension Applications, 1889-1932, Mississippi Department of Archives and History, Jackson, Mississippi; JDSH Register, 360.

[8] Frank Childress Pension Application, Tunica County, Mississippi. Mississippi Office of the State Auditor, Series 1201: Confederate Pension Applications, 1889-1932, Mississippi Department of Archives and History, Jackson, Mississippi; JDSH Register, 360. It is unknown if Childress returned to the care of family or was able to support himself. His daughter, Leloa Smith of Clarksdale, Mississippi, is listed as family in the Beauvoir Register, but the only notation about his departure is that Childress received an honorable discharge on December 28, 1936.

[9] Nathan Best’s name sometimes appears as Nathan Bess. “Bess” appears on one of his pension applications (March 1939), in the Biloxi City Directory in 1931, in the Beauvoir home register, in Beauvoir payroll records, and on the death certificate issued by the state of Mississippi. “Best” appears in his July 1930 pension application, in Harrison County Chancery Court records, in newspaper articles, in a WPA interview, and in correspondence from Beauvoir. I am using “Best” because the use of “Bess” in the home may have started with a misunderstanding or error during Best’s admission which throughout his time at the home and because this is the version of his surname recognized by a descendant and by historians. Special thanks to Jane Shambra, Charles Sullivan, and Deanne Stephens for helping me to unravel this mystery.

[10] Laws of the State of Mississippi Appropriations, General Legislation, and Resolutions Passed at the Regular Session of the Mississippi Legislature … 1932 (Meridian, Mississippi: Interstate Printers, Inc, 1932), 53-54; Laws of the State of Mississippi Appropriations, General Legislation, and Resolutions Passed at the Regular Session of the Mississippi Legislature … 1934 (Jackson, Mississippi: Tucker Printing House, 1934), 17.

[11] “Interview with Frank Childress and Nathan Best,” Folder: Interviews, War Related, Box 10700, Series 447, RG 60: Work Projects Administration, Mississippi Department of Archives and History, Jackson, Mississippi. Very few Beauvoir records exist for the 1930s – Board Meeting Minutes or Biennial Reports would have likely touched on any changes to allowances, but those records from the 1930s have not been found. A ledger listing what each resident was provided between 1930 and 1934 has been located, and verifies that Frank Childress and Nathan Best were provided notably fewer items than white residents. See untitled ledger listing items provided to residents, 1930-1934, Jefferson Davis Presidential Library, Biloxi, Mississippi.

[12] Henry Best died in 1860. His widow, Mariah Best’s, combined real and personal estate in 1860 was $100,000. See 1860 U.S. Federal Census, Tysons Marsh, Greene, North Carolina; Roll: M653_899; Page: 321; Family History Library Film: 803899; 1860 U.S. Federal Census – Slave Schedules. Digitized online, Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2010. Original source: United States of America, Bureau of the Census. Eighth Census of the United States, 1860. Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, 1860. M653, 1,438 rolls.

[13] See Nathan Best in 1870 U.S. Federal Census, Snow Hill, Greene, North Carolina; Roll: M593_1140; Page: 497AB; Family History Library Film: 552639. Rufus Best lists his combined personal and real wealth at $15,000 in the 1870 U.S. Federal Census, Olds, Greene, North Carolina; Roll: M593_1140; Page: 470B; Family History Library Film: 552639. Mariah Best has not been found in the 1870 Census, but by 1880 she was still listed as the head of her household. 1880 U.S. Federal Census, Snow Hill, Greene, North Carolina; Roll: 965; Family History Film: 1254965; Page: 67B; Enumeration District: 065; “Interview with Frank Childress and Nathan Best,” Folder: Interviews, War Related, Box 10700, Series 447, RG 60: Work Projects Administration, Mississippi Department of Archives and History, Jackson, Mississippi.

[14] 1910 U.S. Federal Census, Beat 4, Jackson County, Mississippi; Roll: T624_744; Page: 3A; Enumeration District: 0064; FHL microfilm: 1374757; 1920 U.S. Federal Census, Beat 5, Jackson County, Mississippi; Roll: T625_879; Page: 2B; Enumeration District: 70.

[15] Best’s age listed in the register when he entered the home in 1932 is 90. His death certificate indicates, however, that he was born in 1849, which would have made him 83. JDSH Register, 360. “Residents-Black Inmates” folder, Beauvoir, Soldiers Home Reports, Jefferson Davis Presidential Library, Biloxi, Mississippi.

[16] “Two Colored Veterans at Beauvoir One of Whom Served North as Well,” The Mississippi Guide, November 13, 1936. Transcription in Folder 12, Box 1, “Beauvoir,” Stevens Collection, McCain Archives, University of Southern Mississippi, Hattiesburg, Mississippi.

[17] Nathan Best interview, The Guide, November 13, 1936, Box 128J, Folder: “Racial Groups,” WPA Collection, Mississippi Department of Archives and History.

[18] Nathan Best, Confederate Pension, Form No. 5, Servant, Harrison County, Mississippi. Mississippi Office of the State Auditor, Series 1201: Confederate Pension Applications, 1889-1932, MDAH; Biloxi Daily Herald, January 18, 1940.

[19] Rosenburg, Living Monuments, 136.

[20] Williams, My Confederate Home,242.

[21] JDSH Register, 360.

]]>Over a three-year period, researchers at the University of Southern Mississippi studied the Jefferson Davis Soldiers’ Home in an effort to understand the experiences of the 1,845 men and women who lived there from 1903 through 1957. The team created a random representative ten-percent sample from a list of residents, and located more information about them in the original home Register. This included their date of admission, name, age, county of residence, and the military unit in which the veteran or the widow’s husband served. Death or discharge dates are usually included as well, and sometimes notations about residents’ re-entry, burial location, and family contact information are added. Researchers used this information to dig more deeply into each sample resident’s history through digitized census, military service, pension, and newspaper records. These sources offered insights into veterans’ and their families’ prewar and postwar wealth, slave holding status, educational levels, literacy rates, property ownership, wartime injuries, infant and adult mortality rates, and early-twentieth century financial stability. Supplementing all of this were surviving Beauvoir board meeting minutes and biennial reports, along with some hospital and supply ledgers, limited superintendent correspondence with residents and their families, and a few personal accounts from inmates, as they were known at the time.

Some of the key findings from this project include:

- Most white residents of Beauvoir enjoyed significant financial stability in their youths and into the twentieth century

- The majority of residents lived in upper-class households in 1860

- The average age of Beauvoir residents in 1860, when President Abraham Lincoln was elected and the first southern state seceded from the Union, was 16 years old.

- White prosperity faded significantly after the war, but the majority of Beauvoir residents still enjoyed middle-class status in their communities.[1]

- Residents may have been “the poorest of the poor,” as historians have described them, when they arrived at Beauvoir, but that misleading phrase ignores the benefits of wealth that many residents enjoyed as children and adults.

- The vast majority of residents described themselves as literate, and more than fifty percent had attended school.

- Home ownership records were only available for half of the sample, but among those residents, two-thirds owned their owned homes in 1900 and 1910, indicating, along with the other data, that many of Beauvoir’s residents enjoyed financial security through most of their lives.[2]

Beauvoir Veteran Project Complete Data File

List of Male and Female Residents at Beauvoir, 1903-1957

[1] “Middle class” is a term that can have diverse meanings in nineteenth-century America. The Beauvoir Veteran Project utilizes the financial class parameters for poor, middle, and upper class utilized by Joseph Glatthaar in Soldiering in the Army of Northern Virginia: A Statistical Portrait of the Troops Who Served under Robert E. Lee (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2011), 7. He defined the poorer economic class as having a combined wealth (real and personal property) as ranging from $0-$799, the middle class as $800 through $3,999, and the upper class ranging from $4000 or more. In 1860, residents lived in families that enjoyed an average household wealth of almost $12,000. In 1870, that wealth dropped to $1,100, but remained solidly middle class.

[2] Of those home-owners, nearly fifty-percent had paid off their mortgage.

]]>

Raised on a farm in Jones County, Mississippi, John Andrew Sellers was about 26 years old when the war began with an estate valued at $1000 and estimated his personal wealth estimated at $15,000, likely tied to the eight slaves he or his father (also named John) owned. The elder John Sellers’s estate was even larger, valued at $15,000 with a personal wealth close to that of his son’s. Sellers joined the “Rosin Heels” in August 1861 “for the war” and mustered into Confederate service as a private in Company B, 27thMississippi Volunteer Infantry Regiment. Captured at Lookout Mountain in November 1863, Sellers was sent to the Union prisoner of war camp at Rock Island, Illinois. He remained in captivity for the next year and a half until he was paroled in the spring of 1865.

The Sellers’ postwar world differed drastically from the life they had known. In 1870, John Andrew Sellers was farming again, but his estate had dwindled to $220 with a personal wealth of $660. His father had been similarly reduced and noted nearly the same wealth to the census taker, and things do not appear to have improved by 1880, which found John and his first wife, Mary Easterling, still farming in Jones County with nine children and one on the way. Mary died in 1881 and John remarried five years later to Lydia Bynum, but she died a year later in June 1887. A year after that was when John, then 54, married Nancy Hawkins, just 20 years old.

John and Nancy Hawkins Sellers had eight children of their own amid the poverty that continued to plague them. When he finally applied for a Confederate pension in 1917, Sellers listed himself as a farmer with the same wealth he had claimed almost fifty years earlier. Ironically, he never lived at Beauvoir. Sellers died in 1922 in Forrest County, Mississippi, where he and Nancy lived with five of their children. But his Confederate pension made it possible for Nancy to enter the home, though she waited until 1953. It could be that her grandchildren — she was living with three of them, listed as the head of household, in 1940 in Hattiesburg, Mississippi — could no longer care for her, but the exact cause for the move is unknown. And her stay was brief. In early 1953, Nancy Sellers entered the Beauvoir home, but she received an honorable discharge at the end of May that year, and died that August back home with her family in Hattiesburg.

The post-Civil War South is remembered for its social, political, and economic chaos and the rise of the Ku Klux Klan. It is studied as an age of great possibility as enslaved peoples embraced their hard-won freedom, and it is popularly remembered for Tara-like plantations crumbling amid broken fortunes and dark futures.

Rarely mentioned, though, are those Southerners like John and Nancy Sellers who lacked the postwar security to preserve and publish their wartime writings, assuming these veterans and their families were sufficiently literate to have written during the war. In John Andrew Sellers’s case, he was certainly literate. But that is not true of many of the Beauvoir residents. And even in Sellers’s case, we have found no record of wartime letters or other papers to help us learn more about this family.

With the majority of our Civil War soldier studies based on wartime and postwar correspondence and publications, we have a gaping hole in our knowledge when it comes to those impoverished Southerners who entered Confederate homes from Richmond to Austin in the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries. Due to the limited record keeping at places like Beauvoir and modern privacy laws that hinder historians’ ability to access what papers do exist, we know very little about veterans’ lives within the homes. Existing studies of institutions like Beauvoir indicate that those who lived there were known as inmates, not residents, and they often complained of the controlling habits of their administrators and governing boards. Homes served as monuments to the Lost Cause where residents became caricatures of “old times … not forgotten.” Indeed, historians of the Civil War veteran experience have argued persuasively that our understanding of these men and their families have been shaped more by what the public — then and in subsequent generations — chose to preserve, share, and remember than any true sense of who these men and women where and what their postwar lives were like.

In the fall of 2014, my colleague, Deanne Nuwer, and I launched “The Beauvoir Veteran Project” (BVP) at the University of Southern Mississippi. The BVP seeks to cut through the mists of memory to understand the lives and experiences of the veterans, wives and widows who found themselves at the Jefferson Davis Soldier Home — Beauvoir in Biloxi, Mississippi, between 1903 and 1957. Of course, the challenges in studying impoverished and largely illiterate people remain; we have found no new sources. But modern digitization efforts make it easier than ever to learn about the men and women who spent their latter-most years at Beauvoir. We have had particular success with the census records of 1850, 1860, and 1870, as well as the slave schedules, which allow us to map the trajectory of veterans’ socio-economic lives before and after the war. Compiled service and pension records offer insights into their experiences in uniform thanks to notes on wounds, imprisonment, hospitalization, desertion, promotions and demotions, as well as their economic status late in life. Finally, nineteenth-century newspapers reveal how these men and women were seem by their communities. All of these recently digitized records allow us to paint a far more detailed and accurate image of the men and women who have remained largely in the shadows of the Civil War era.

Utilizing the same methods that led to the creation of my statistical sample of the over 7000 men who served in the Texas Brigade, Deanne and I created a sample of the approximately 1850 men and women who lived at Beauvoir in the first half of the twentieth century. We’ll be launching the BVP website next month, where visitors can read about some of the findings that our undergraduate and graduate researchers have been working on since August. You can also check us out online to learn about Beauvoir residents who still need to be researched and how volunteers can contribute to the BVP. We’ll announce the Beauvoir Veteran Project via my personal page on Facebook, as well as on the Dale Center’s Facebook page, so please stay tuned to learn more.

* Special thanks for their key role in our research on Beauvoir are due to Jane and Charles Sullivan, PRCC, as well as USM student JoAnna Gunnufsen for her research on the Sellers.

X-post from the Dale Center for War & Society’s blog “Reflections on War & Society” by Dr. Susannah Ural.

Susannah Ural, Ph.D., is Co-Director of the Dale Center for the Study of War & Society at Southern Miss and is the author of Don’t Hurry Me Down to Hades: The Civil War in the Words of Those Who Lived It (Osprey, 2013) and The Harp and the Eagle: Irish-American Volunteers and the Union Army, 1861-1865 (NYU Press, 2006). Her current project, Hood’s Boys: The Soldiers and Families of Hood’s Texas Brigade, will be published in 2015 by LSU Press.

]]>- Download the “Beauvoir Veteran Project – Database Template“ — This is the Excel database template that every researcher uses to enter and save the Federal census data on the veteran, wife, or widow they are researching. After entering the information for each decade (which you’ll see are separate “tabs” at the bottom of the spread sheet — 1850, 1860, 1870, etc.) the researcher will save the file as “Beauvoir Veteran Project – Last name, First name Middle initial/name (if available)” for each veteran/wife/widow they research. See the example file “Beauvoir Veteran Project – Anderson, Volney H.xlsx” as an example of how researchers should save EACH person’s data. Again, remember that each veteran, wife, or widow’s data is saved as a separate file. NOTE: Don’t worry if you can’t find data for 1890; the census records for that year were almost all destroyed in a fire.

- Download the “Beauvoir Veteran Home – Female Residents” and “Beauvoir Veteran Home – Male Residents” — This is the list of all residents. You can see here how we have skipped to the third male and female name at the start of each list, and then highlighted every 10th name, creating a data sample of about 10 percent of the veterans who lived at Beauvoir. In all, there were 694 women and 1155 men, totaling 1849 residents between 1903 and 1957. We’re sampling about 185 people.

- Download the “Blank Census Forms 1850-1940” — These are helpful in case students/volunteer researchers want to hand enter their veterans’, wives’, widows’ data and then type it into the Excel template.

- Gathering data — Please save (digitally) EVERY card in the veteran’s military/compiled service record that you find in Fold 3. We also need you to save the summary page from Ancestry where you find the veteran/wife/widow in the census records. You can create links to these in your data entry sheet if you like — see “Anderson Volney H Census Data.pdf” for an example of how to do this.

- If your veteran or resident was a slaveholder, record a summary of their 1850 and 1860 Slave Schedule — We would like you to look for each veteran, wife, or widow in the 1850 and 1860 Slave Schedules as well. Simply note if you can find them, and how many slaves they or their family owned. This will help us evaluate their wealth from the antebellum to postwar years. Save the summary pages, just as described above, and save it in a word file labeled with their first and last name (ie “SmithJamesSlaveSchedule.docx”).

- Save images of their Compiled Service Records — These are the military service records of a veteran. Since admittance to the Beauvoir veteran home required veteran status, we know there is a very likely chance of finding their service record. Some are lost, some misfiled, but the majority of veterans should have service records. Again, as noted above, save and upload EVERY service card for the veteran under study. For some, this could be as many as 100 cards. For many, though, it’s anywhere from 2 to 18 cards. Please save these in a folder labeled with their last name (ie “SmithJamesServiceRecords).

- Send these forms to beauvoirveteranproject@gmail.com

- Please save all of the data you find in a single folder with a title featuring the veteran/wife/widow’s name. In the case of Volney Anderson, I’d title the folder “Volney Anderson.”

- In that folder, save an image of EACH card in the veterans’ compiled service record (CSR), either screen shots or actual images of the each census record you find, digital copies of his or her pension application, and anything else you find on this individual.

- It would also be helpful to create subfolders to contain all of this – a subfolder titled “Census,” another titled “CSR,” another titled “Newspapers” if you find anything in online newspapers, another titled “Pension Application,” etc.

- When you have saved all of your findings into one large folder, please send it to us at beauvoirveteranproject@gmail.com .