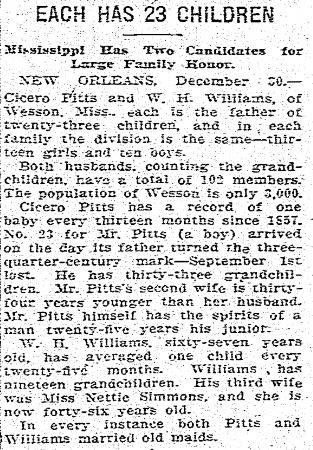

In 1907, the Richmond Times Dispatch published an article about two men from Wesson, Mississippi, who claimed to be the fathers of twenty-three children each. One of these men was a former private in the 36th Mississippi Infantry named Cicero Pitts. He had fathered a baby, as the Time Dispatch noted, an average of once every thirteen months from his early twenties until he was seventy-five years old.

In 1907, the Richmond Times Dispatch published an article about two men from Wesson, Mississippi, who claimed to be the fathers of twenty-three children each. One of these men was a former private in the 36th Mississippi Infantry named Cicero Pitts. He had fathered a baby, as the Time Dispatch noted, an average of once every thirteen months from his early twenties until he was seventy-five years old.

Pitts was born in Georgia in 1833 before his family moved to Copiah County, Mississippi, where his parents (Wesley and Milly) established a plantation. He remained in Copiah after marrying his first wife, Matilda, who gave birth to their first child in 1859. According to the 1860 U.S. Census, Cicero Pitts’s estate was worth a respectable $1,280 and he also owned three slaves—a twenty-two year old woman, a two year-old boy, and a six-month old baby girl.

Like many men his age with families, Pitts did not enlist in the Confederate Army immediately after the Civil War started. Instead, he waited until May 2, 1862, when he enlisted for twelve months in Company E of the 36th Mississippi Infantry. Pitts and the 36th Mississippi spent much of the summer operating around Corinth, until September when they joined Major General Sterling Price’s army in Iuka as part of Colonel John D. Martin’s brigade.

Determined to prevent the Confederates from consolidating forces in Iuka, Mississippi, Major General Ulysses S. Grant ordered Major General William Rosecrans to drive away Price’s army of 3,179 men. On September 19, 1862, Rosecrans attacked the rebels two miles south of town around 4:30 pm. Forty-five minutes into the battle, the 36th Mississippi supported Brig. General Louis Hébert’s brigade as they counterattacked and temporarily captured a battery of Union artillery. Fierce fighting followed as the opposing forces alternated control of the field several times until a final bayonet charge by Martin’s brigade and the 36th Mississippi failed to drive the Federals back.

By the time Price withdrew his army from Iuka, twenty-two soldiers from the 36th Mississippi had been killed or wounded—including Cicero Pitts, who had been shot through both thighs and taken prisoner. The U.S. Army soon paroled Pitts, who returned home to recover from his wounds. Although the Confederate Army’s records do not mention his condition after October 1863, Pitts later stated on his pension application that he received a medical discharge due to the severity of his wounds. He had only been in the army for eight months.

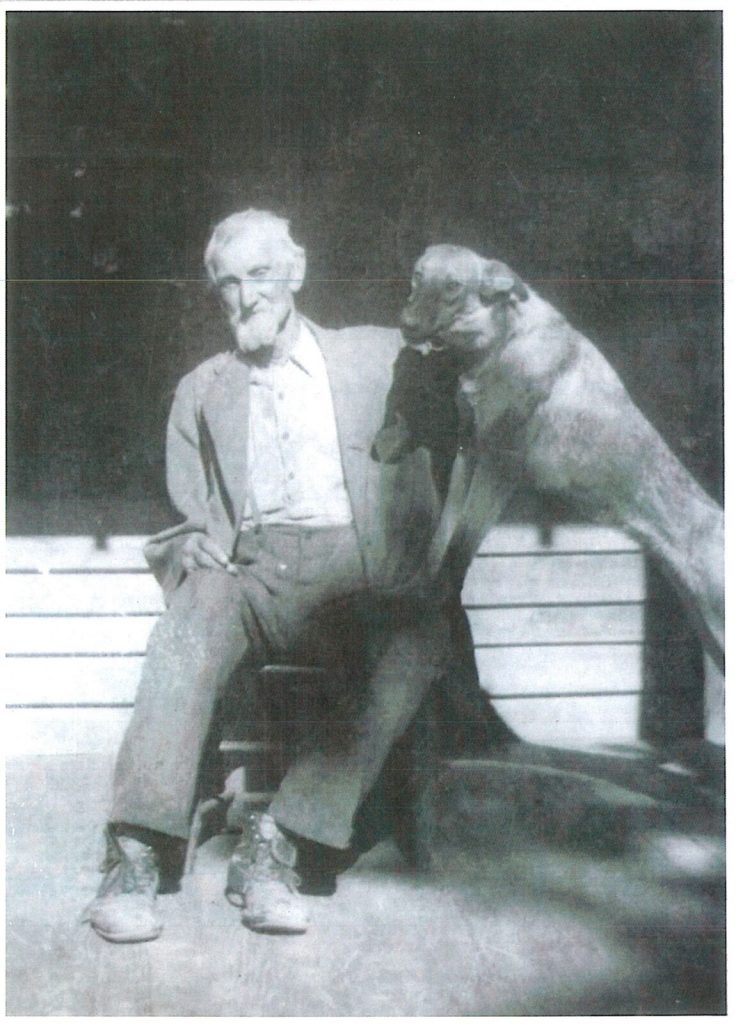

Pitts remained in Copiah County after the war where he and Matilda farmed and raised their ever-increasing family. Matilda Pitts died sometime after 1880 and Cicero married Martha “Mattie” White, who was thirty-two years his junior. Many of Cicero Pitts’s children continued living on his farm as adults, and several of them worked at the textile mills in nearby Wesson.

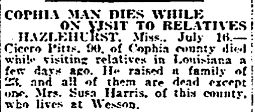

Pitts moved into the Jefferson Davis Soldiers Home on March 22, 1920 when he was eighty-seven years old, but he was discharged the following May. He died on June 30, 1921 while visiting family in Allen Parish, Louisiana, where he is buried. Mattie Pitts lived until 1931, and she is buried in Copiah County.

Lead author: Allan Branstiter, Southern Miss history doctoral candidate. Lead researcher: Armendia Hulsey, Southern Miss history student.

]]>Not much is known about Peyton S. Webb’s time in the Confederate Army. He was only thirteen or fourteen years old when the war started, and he stated later in two pension applications that he enlisted in May 1864 as a private in Company E of the 4th Mississippi Infantry. Webb fought alongside the officers and men of Brig. General Claudius W. Sears’s brigade who broke through the Union line during the Battle of Franklin on November 30, 1864. A Confederate casualty report listed him among those wounded during the battle, but Webb stated on his applications that he was never injured. However, Webb and his service records do agree on how his war ended—he surrendered with his regiment in Blakely, Alabama on April 9, 1865 and spent a short time imprisoned on Ship Island and in Vicksburg, Mississippi.

Webb returned home, bought a farm near Winona, Mississippi, and married his first wife, Elizabeth Hill. Peyton and “Lizzie” had six children during their marriage, but only one (a daughter named Mattie) lived beyond 1900. Lizzie died in 1915 and Peyton remarried and began applying for a Confederate pension from the state a year later.

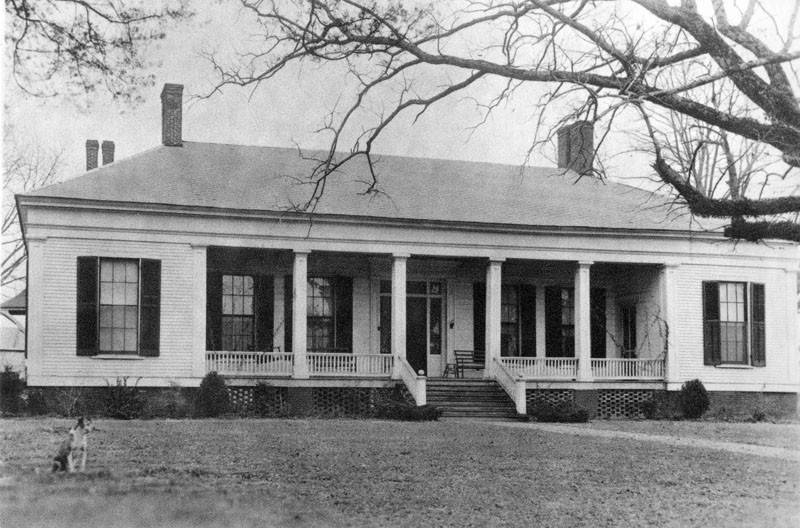

Webb and his second wife, Mary, were invited to live at the Jefferson Davis Soldier’s Home on May 1, 1929. Apparently it took some convincing on the part of the Beauvoir’s superintendent, Elthanan Tartt, to get the Webbs to accept the offer. Tartt assured them that while “some people who have never been here seem to think the place is a poor house . . . this is a mistake. Every comfort, freedom, and liberty is given [to] the inmate of the home.” Tartt invited the Webbs try living at Beauvoir knowing that if they did not like the place they could return to Winona.

Mr. and Mrs. Webb moved to the Jefferson Davis Soldiers’ Home the next year. Peyton kept in touch with his daughter and grandchildren through the mail. A few days before Christmas 1931, he wrote to Mattie that he was “all rite” and looking forward to the holidays, although he wished he could return home to celebrate. The staff was preparing for “a big Diner” hosted by United Daughters of the Confederacy, and he would try to buy a present the next time he was in Gulfport. He reminded Mattie how much he looked forward to mail, and urged his granddaughter to write him soon.

Peyton Webb lived on and off at Beauvoir during the early 1930s, reminding historians of the fluidity with which residents could enter and leave the home. He was honorably discharged for the final time in 1934, when he returned to Montgomery County until his death four years later. He is buried at the McKenzie Cemetery located between Duck Hill and Winona, Mississippi. Records do not indicate what happened to Mary Webb.

Lead author: Allan Branstiter, Southern Miss history doctoral candidate. Lead researcher: Lindsey Peterson, Southern Miss history doctoral student.

]]>The Anderson family owned no slaves, nor did they retain a large plantation or invest heavily in cotton production. Instead, they eked out a living practicing what historian Gavin Wright called “safety-first” farming. A poor yeoman-class family, the Andersons were primarily concerned with protecting their property. Land was the key to their sense of independence and social standing. Consequently, they avoided economic risks and speculating in commodity markets. Unlike the planters of cotton country, the Andersons focused on growing enough food to survive the year and only planted staple crops like cotton or tobacco if they had extra acreage and time. What cash they received in return for their staples on the market was used to buy luxuries and supplies they could not grow themselves.

When the Civil War began, Volney was only thirteen years old. His father attempted to enlist in the 27th Mississippi Infantry Regiment during the winter of 1861, but he was quickly discharged for unknown reasons. Volney enlisted with the 24th Mississippi Infantry under the command of General Edward C. Walthall on his sixteenth birthday, April 24, 1864. When he arrived in near Dalton, Georgia, young Private Anderson was greeted by a body of men hardened by years of difficult service on the battlefields of Perryville, Vicksburg, Murfreesboro, Chickamauga, Lookout Mountain. If Volney Anderson was hoping to prove his mettle in combat, he would soon have his chance.

Breaking camp on May 7, 1864, Anderson and 27th Mississippi marched to an entrenched position defending a hard angle on the left flank of John Bell Hood’s Corps at Resaca, Georgia. A week later, they repulsed two Federal charges and sustained heavy casualties. General Hood reported after the battle, “Walthall’s Brigade suffered severely from an enfilade fire of the enemy’s artillery, himself and men displaying conspicuous valor throughout under very adverse circumstances.”

Volney Anderson’s brigade had less than 500 men in the spring of 1864, and the next few months would be extremely costly of the men. The brigade lost fifty-one men at the Battle of Resaca on May 14; sixteen men at the Battle of New Hope Church on May 17; seventy-eight men at the Battled of Ezra Church on July 28; and forty-two men at the Battle of Jonesboro on August 30-31. According to family history, Anderson was grazed just above his ear by a bullet and survived the disastrous defense of Atlanta physically unscathed.

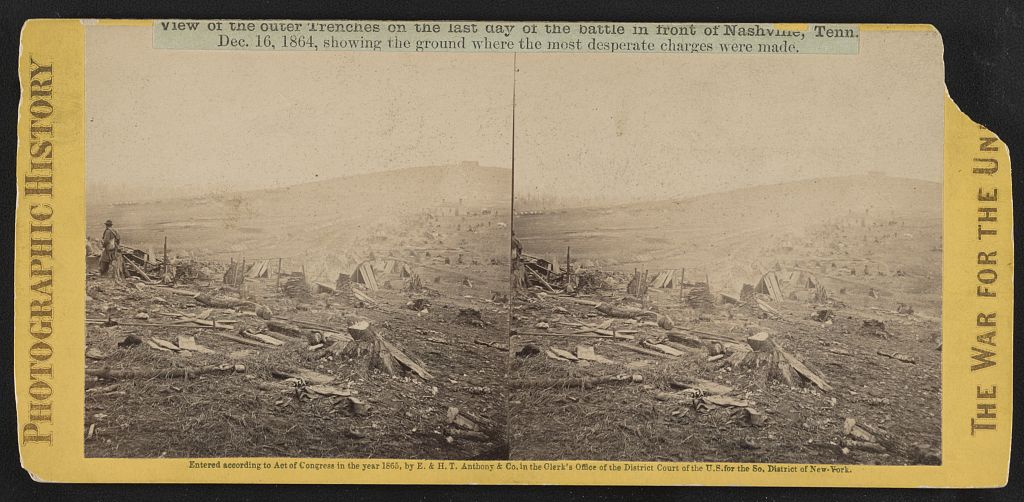

In October 1864, Anderson marched northwards with Hood’s Army and attacked the Union force under Major General John Schofield in Franklin, Tennessee. Hood ordered his men to advance across two miles of open ground (twice as much distance as traversed during Pickett’s Charge at Gettysburg) and attack an entrenched line of Union soldiers. The rebels managed to punch through the first line of Federal defenses, but bogged down when Northern reinforcements arrived. The 27th Mississippi (marching as part of General Stephen D. Lee’s corps) reinforced Hood’s wavering left flank, but the Confederate Army was driven back after sustaining almost 7,000 casualties. Volney Anderson’s brigade lost 76 men killed and 140 wounded. After another costly defeat at the Battle of Nashville, he and what was left of Hood’s Army retreated across the Tennessee River and into Mississippi.

After establishing winter quarters near Tupelo, Anderson and his brigade were granted furloughs until they were ordered to regroup in Meridian on February 14, 1865. Once assembled, Anderson and the remaining 282 men in his brigade made for the Carolinas, where the surrendered with General Joseph Johnston’s army on April 26—two days after Volney Anderson’s seventeenth birthday.

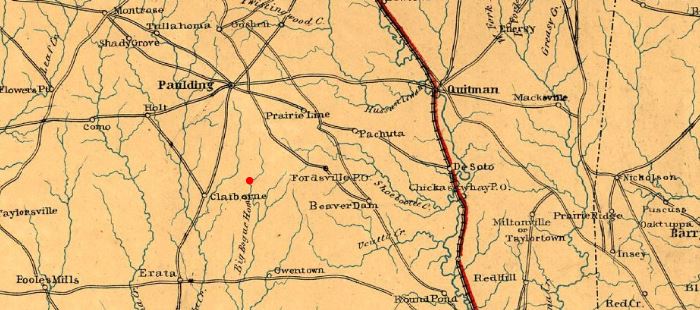

Private Anderson returned to his family’s farm in Heidelberg after the war. On September 3, 1873, he married Nancy McCraney. She was raised in the nearby town of Claiborne by her oldest sister and her husband (Flora and John B. McFarland) after her parents died. Volney and Nancy Anderson had ten children during their 66 year marriage.

In 1881, the Andersons relocated to a burgeoning Pine Belt lumber and railroad hub. Their new town was incorporated and named Hattiesburg, Mississippi the following year. The Andersons were also founding members of First Presbyterian Church. They also sold the timber they grew in plots in nearby Petal and Oak Grove and eventually and became one of the most prominent families in town.

Volney Anderson stopped working sometime after 1910 due to his age. He applied for a Confederate soldier’s pension in 1916 and lived on his farm until he was admitted to the Jefferson Davis Soldiers’ Home in Biloxi on August 9, 1923 (Nancy Anderson was admitted the following October).

They seemed to have enjoyed their time at Beauvoir. Anderson descendants recall Volney enjoying telling guests about his time in the army, and that he once sounded off with a rebel yell when President Franklin D. Roosevelt visited the home in the 1930s. Anderson also told a local paper about a slave who accompanied his company during the war and washed the soldiers’ clothes until an officer “stole” the man. When his grandchildren asked him if he had ever killed a man, Volney stated “I don’t know. But I know that men fell where I was shooting.”

His daughter Bertha, recalls a story her father told about the time he and some men separated from their unit and ran out of food. After traveling a bit and avoiding Union patrols, the starving men came across a farm and stole a goose they found there. Worried that a fire would alert Union patrols of their location, Anderson and his friends snuck into the woods and ate the creature nearly raw. The men inevitably became ill, and Bertha said her father never let his family keep geese on their farm.

The Andersons lived together at Beauvoir until Volney’s death on December 15, 1938 and the age of 91. The funeral was held at First Presbyterian Church in Gulfport, where the pastor read Alfred Lloyd Tennyson’s poem “Crossing of the Bar.” Nancy Anderson died at the home in 1945. Although one of their grandchildren had died in a Japanese prisoner of war camp in the Philippines, the Andersons were survive by ten children, 52 grandchildren, and 42 great-grandchildren. Both Nancy and Volney Anderson are buried at Beauvoir.

Lead author: Allan Branstiter, Southern Miss history doctoral candidate. Research also conducted by Rachael Pace, Southern Miss history student.

]]>

When the Civil War began, James Everett was a twenty-nine-year-old overseer on his family’s plantation. Of the five sons born to the Everett clan, four would serve in the Confederate Army. During the heady days of April 1861, James Everett married Sarah Elizabeth Garner and enlisted in the 22nd Mississippi Infantry; however, he was medically discharged the following October when it became apparent he had asthma.

In 1862, James reenlisted in the army. This time he signed up to serve alongside his brothers Alexander (30) and Charles (16). The Everetts were assigned to Company I of the 4th Mississippi Cavalry, which was comprised of men from Amite, Wilkinson, Pike, and Franklin counties. The brothers fought side by side during skirmishes around Port Hudson and against General William T. Sherman’s march from Vicksburg to Meridian.

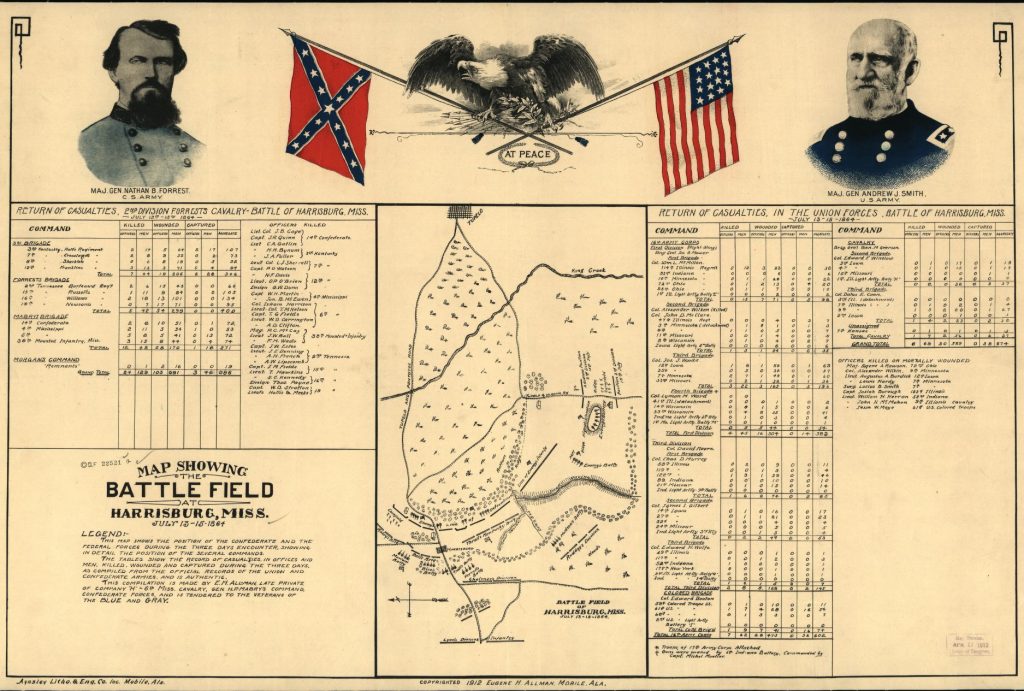

At some point during the fighting in northern Mississippi in late 1863 and early 1864, Marshall Everett joined his older brothers and the 4th Mississippi Cavalry. Since the seventeen-year-old Marshall does not have his own service record, he may have never officially enlisted in the Confederate army. Nevertheless, the young man accompanied his brothers to Harrisburg, Mississippi, where they attacked the U.S. Army’s fortified line south of the city on July 14, 1864. The uncoordinated rebel assault was ultimately repulsed and six men of the 4th Mississippi were killed that morning. Among the dead was Marshall Everett, whose body was returned to Amite County and buried in the family cemetery.

The remaining Everett men remained with their regiment until the end of the war. On November 4-5, 1864, they were part of General Nathan Bedford Forrest’s successful raid of a U.S. supply depot in Johnsonville, Tennessee. The attack destroyed millions of dollars worth of equiptment, including four gunboats, fourteen transport vessels, twenty barges, and twenty-six artillery pieces. Eventually, the men surrendered with their command in Gainesville, Alabama, on May 12, 1865.

After the war, James Everett returned to his wife and young daughter (Lula) and began farming in Amite County. Like much of the slaveholding class, the Everetts’s experienced significant financial losses due to the abolition of slavery and sinking cotton prices. By 1870, the combined value of the family’s holdings totaled up to $3,824—over $38,000 less than what they had a decade before. Still, they enjoyed a level of wealth that was significantly higher than many of their neighbors.

James Everett remained in the county until his wife’s death in 1889. Then sixty-nine years old and unable to work, he moved into his brother-in-law’s home in Little Springs, Mississippi and applied for a Confederate veteran’s pension. Citing the case of asthma he contracted while in the infantry in 1861, the state offered him $25 a year.

In 1899, Amite County Sherriff J. B. Turnipseed auctioned off the James Everett’s property to pay for delinquent taxes, and the state approved his second pension application for $780 per annum in 1900. Everett moved into the Jefferson Davis Soldiers’ Home at Beauvoir on January 14, 1907, and lived there until he died twelve years later. He is buried on the grounds of the home.

Lead author: Allan Branstiter, Southern Miss history doctoral candidate. Lead researcher: Southern Miss History major Rebecca Applewhite.

]]>Three of the Coker men served in the Confederate Army during the Civil War. Elder brothers Aleazer and John, enlisted with the 7th Mississippi Infantry in September, 1861. Shade Coker—then seventeen years old—enlisted with Garland’s Battalion of militia cavalry on August 8, 1862, possibly seeking militia service in the hope that this would let him remain home to help with family. Although he enlisted for a three-year term, Shade only remained with his militia unit until April 30, 1863. It is unclear why he left, but it is possible that his brothers may have had something to do with his decision.

On September 14, 1862, Aleazer and John participated in General James R. Chalmers’s poorly planned assault on Union fortifications outside Munfordville, Kentucky. John was struck by a blast of grapeshot and both brothers were captured when Chalmer’s withdrew. They were sent briefly to the Union prison in Cairo, Illinois, before they were exchanged and sent back to the rebel army. Instead, John Coker returned to Pike County without permission. His brother Aleazer returned to the 7th Mississippi Infantry and served with distinction at the Battle of Stone’s River, where his bravery won him a place on the Confederate Roll of Honor—however, he also deserted from the army and returned home by late 1862 or early 1863.

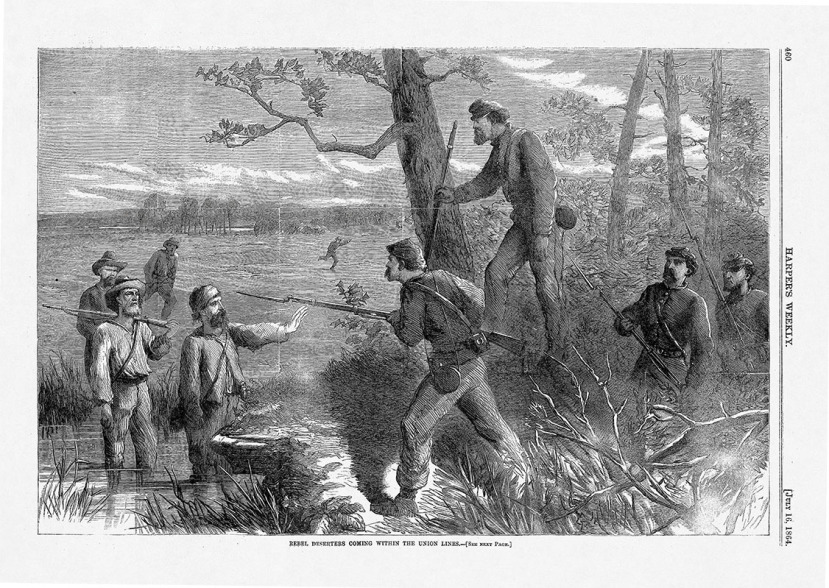

All three of the Coker brothers had abandoned Confederate military service by the time Ulysses S. Grant’s Union army invaded Mississippi during the spring of 1863. Discontent with the Confederate government was growing on the Mississippi home front and hundreds of deserters took to the hills, woods, and swamps. John Coker’s wound was probably reason enough for conscription agents to leave him alone, but Confederate authorities issued a warrant for Aleazer’s arrest during the winter of 1863-1864. Only Shade Coker returned to the army when he served as a teamster from August 1 to September 30, 1864 with the 38th Mississippi Cavalry.

After the war ended, the Coker brothers remained close to home. Sometime before 1870, Shade married a widow name Mary Malinda Collins (née Price) and became a tenant farmer near Brookhaven, Mississippi, where they raised her children and had children of their own. The Cokers would not stay in Brookhaven long, as Shade began looking for opportunities in the burgeoning industrial sector in nearby Wesson.

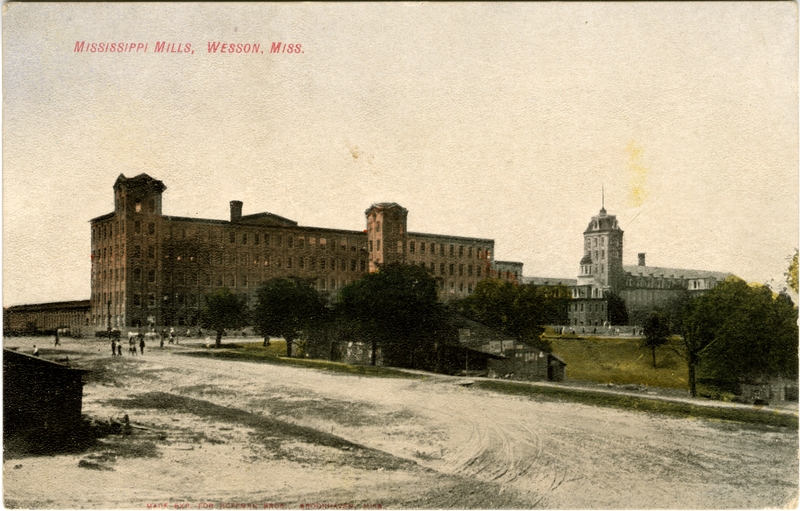

When the Cokers moved to Wesson it was home to the Mississippi Manufacturing Company (renamed Mississippi Mills in 1873) and a rapidly expanding factory town. The textile mill was built in 1866 by James Madison Wesson and sold to William Oliver and John T. Hardy after it went bankrupt in 1871. After the mill burned down two years later, Hardy convinced Edmund Richardson, one of the richest men in Mississippi, to become a partner and finance the construction of a more modern facility. Richardson soon bought out Hardy and—with Oliver acting as general manager—built four large mill complexes in Wesson between 1873 and 1894.

Life in Wesson was dominated by Mississippi Mills. A strict prohibitionist, James Madison Wesson made sure that the southern border of dry Copiah County jutted far enough south to include his factory. Fueled by the jobs provided by the mill, Wesson’s population skyrocketed from 464 residents in 1870 to 3,168 residents by 1890. Electric lights were installed in the factory in 1882, allowing textile production to continue into the evening. By the 1890s, the mill employed 1,200 workers who produced 4 million yards of cotton goods, 2 million yards of wool, and 320,000 pounds of yarn and twine annually.

Among the people employed at Mississippi Mills in 1880 were Shade Coker and three of his children, Augusta (23), Eugene (18), and Zeno (12). On February 28, 1897, his wife Malinda died and was buried in her parent’s family plot in Bogue Chitto, Louisiana. A year later, Shade Coker married his second wife, Bettie (who was thirty years his junior), and began renting a home apart from his children. In 1900, Shade Coker was still working at the mill, while his children lived in the home owned by his eldest step-daughter, Augusta.

According to the 1910 Census, Shade and Bettie Coker purchased a farm in Brookhaven while his children remained in Wesson. In 1906, Mississippi Mills was forced into receivership having never recovered fully from the death of Edmund Richardson and the Panic of 1893. As a result, only one of the Coker children (Sallie, 39) still worked at the mill, while Augusta took care of the household work and Willie (at 37, the youngest of Shade and Malinda Coker’s children ) sold gum on the street.

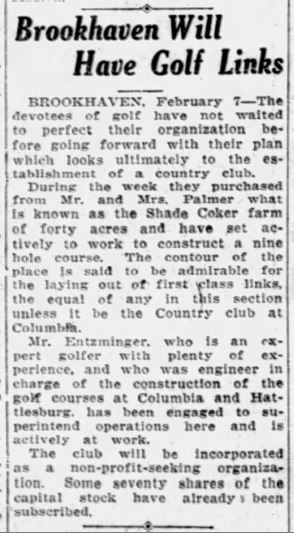

Shade and Bettie Coker were fixtures in the social life of their community at the turn of the twentieth century. In 1909, Bettie judged a baby show at the Lincoln County Fair, while Shade became an active figure in local veterans affairs. The Cokers appear to have lost a significant amount of their savings in 1914 when the Commercial Bank and Trust of Brookhaven failed, but they retained control of their dairy farm until at least 1920.

In 1923, Shade and Bettie sold their forty-acre dairy farm and moved into the Jefferson Davis Soldiers’ Home. After a brief stay at Beauvoir, they removed for unknown reasons to Sheffield, Alabama, where Shade died of pneumonia soon thereafter on April 16, 1924. Only 45 year old, Bettie relocated to Hot Springs, Arkansas and finally New Orleans, where she passed away on May 23, 1938. The Brookhaven Country Club now stands on the land once occupied by the Shade Coker farm.

Lead author: Allan Branstiter, Southern Miss history doctoral candidate. Lead researcher: Robert Farrell, Southern Miss MA history student.

]]>

The realities of camp life took their toll on the Walker brothers. Army records state that John contracted one of the many camp illnesses even before leaving Mississippi. Conditions worsened when the 16th Mississippi arrived in Virginia and set up camp next to a North Carolina regiment suffering from a measles outbreak. Despite relocating to a new camp near Centreville, Anderson Walker contracted typhoid fever and died on September 19, 1861. Winter offered no respite to young John, and he was hospitalized again for an unnamed illness in January-February 1862.

Private Walker rejoined his regiment in time to participate in General Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson’s Valley Campaign. After fighting with Jackson’s Army of the Valley at the battles of Winchester and Cross Keys, the 16th Mississippi marched east towards Richmond in time to confront Major General George B. McClellan’s army during the Seven Days Battles. The regiment was then transferred to Brig. General Winfield S. Featherston’s brigade. Despite the fact that he and his division were held in reserve during the final Confederate attack at the Battle of Second Manassas, John Walker sustained a serious wound on August 30, 1862.

Confederate records indicate that Walker spent five months recovering from vulnus sclopeticum—a gunshot wound—before returning to his unit on February 23, 1863. He and the rest of 16th Mississippi fought at Chancellorsville (suffering seventy-six casualties) and Gettysburg, where they lost nineteen men during a disjointed attack on the Union line on Cemetery Ridge on July 2, 1863.

The 16th Mississippi did not see significant combat again until May 1864, when they fought at the battles of the Wilderness and Spotsylvania Court House. Walker suffered another wound during the fighting around Cold Harbor on June 6 and was promoted to corporal after reuniting with his regiment just over a month later. He fought at one more battle—the Battle of Weldon Railroad, also known as the Battle of Globe Tavern—where Union soldiers captured Walker during a reckless attack on entrenched Federal artillery on August 21.

Walker arrived at the Federal prisoner of war camp at Point Lookout, Maryland on August 24 and remained there until he was paroled on March 14, 1865. According to an early biographer, Walker attended a school organized by prisoners at Paint Lookout.

After the war, Walker returned to Pike County, engaged in planting, and married Mary Jane “Molly” Magee, the daughter of a wealthy former slaveholder. In 1872, he established a general merchandise store that boasted $75,000 in annual sales by the 1880s. Molly and John named their first son Jefferson Davis Walker and adopted a boy named Oscar Alford in 1874. Neither of their sons survived past 1907.

In 1873, John helped his father-in-law, Obed Magee, transfer land to the Magee’s former slaves after a suspicious fire destroyed their church—now known as Rose Hill Missionary Baptist Church in Magnolia, Mississippi. Local family history also states that Molly Magee Walker was close to a half-sister named Elva (or Elvie) that her father had with an enslaved woman named Rachel.

John Walker was elected to the Pike County Board of Supervisors for eight consecutive years and represented the county in the legislature for one term as a member of the Democratic Party during the 1880s. He also served as a justice of the peace for a number of years. The first iron bridge across the Bogue Chitto River was also named after him.

Walker maintained a farm in Pike County until around 1910, when the U.S. Census listed him as a boarding house keeper. Mollie died two years later and is buried in the Magee family cemetery near Magnolia. According to the 1920 Census, Walker lived in the home of Eugene P. Magee—Molly’s nephew—in Laurel, Mississippi. Two years later, in June 1922, John Walker was admitted into the Jefferson Davis Soldier Home, and he lived there until his death on October 19, 1923. He is buried in Magee, Mississippi.

Lead author: Allan Branstiter, Southern Miss history doctoral candidate. Lead researcher: Lindsey Peterson, Southern Miss history doctoral student.

]]>When Thomas Dandridge died in 1842, he had saved enough money to leave each one of his children $440 in land (about $11,116 in 2016). He also left the control of the plantation and eight slaves to his widow, who continued to manage the estate while seeing to her children’s’ education. By 1860, the Dandridge’s land and twenty-four slaves were valued at $32,000 (about $867,715 in 2016).

Powhatan Bolling Dandridge attended the University of Mississippi during the late 1850s before moving on to the Medical College of South Carolina in Charleston (now the Medical University of South Carolina). In 1860, he wrote a thesis investigating malarial fever, earned his MD, and returned to Mississippi to live with his mother and practice medicine.

In 1862, Dr. Dandridge was appointed as the surgeon of the 3rd Mississippi Cavalry, a state militia unit originally organized to serve as minute men. Throughout the winter of 1862 and summer of 1863, the regiment operated locally to counter Union raiding across the Tennessee border. From mid-to-late June 1863, the 3rd Mississippi Cavalry supported the Confederate effort to defend Vicksburg, though they were not captured when the city fell to Union control in July. In August, General James R. Chalmers ordered the regiment to locate and arrest Confederate deserters and conscripts in the state.

After Chalmers was forced to abandon his headquarters in Grenada, Mississippi, the 3rd Mississippi Cavalry and Dr. Dandridge regrouped in Abbeville and attempted to raid William T. Sherman’s supply line in Collierville, Tennessee in October 1863. Although they were able to capture or destroy a significant amount of Union supplies south of Memphis (including General William Tecumseh Sherman’s horse, Dolly), the rebels were ultimately forced to withdraw back to Mississippi. On February 22, 1864, the 3rd Mississippi Cavalry participated in General Nathan Bedford Forrest’s defeat of General Sooy Smith’s expedition at the Battle of Okolana.

On January 6, 1864, General Chalmers (who usually disdained militia units) praised the professionalism and fighting ability of the 3rd Mississippi Cavalry and urged the Confederate Government to enlist the regiment into regular service, which they did. Dr. Dandridge was not among the men who wanted to be folded into the Confederacy’s regular army, however, and he transferred to the 7th Mississippi Cavalry (also known as the 1st Partisan Rangers) instead of accompanying the 3rd Mississippi Cavalry to Georgia in July 1864. Dandridge remained with the 7th Mississippi Cavalry until the end of the war and surrendered at Selma, Alabama on May 4, 1865.

Dandridge began courting Sylvia Lyon, the daughter of a very wealthy planter from Chickasaw County, when he returned home from the war. The pair married in 1866 and had a daughter, Virginia Louise Dandridge, on May 18, 1867. Like many of Mississippi’s former slaveholders, the Dandridges lost an immense amount of wealth after the Civil War. Dr. Dandridge owned real estate in Ellistown, Mississippi valued at just $20 in 1870. He did, however, own $2,000 in personal property, most likely materials associated with his medical practice.

In 1880, Dr. Dandridge had moved his medical practice to nearby Union County, Mississippi. Four years later his daughter married a local farmer named George Lacy Hall and gave birth to a son in 1893. She continued to live in the area until her death in 1939.

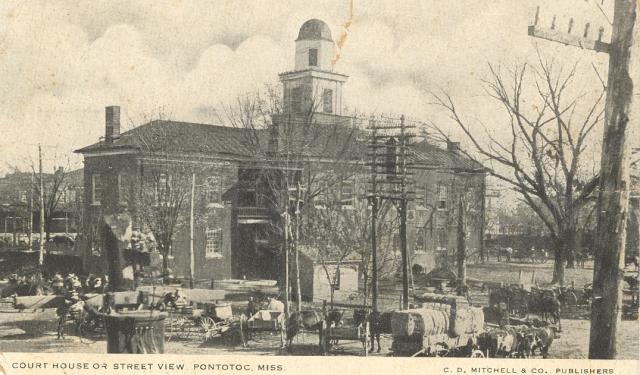

Like many veterans before the widespread use of pensions and social security, Dr. Dandridge struggled to make ends meet as he grew older and less capable of earning an income. His wife, Silvia Dandridge, died sometime after 1880 and by 1900, Dr. Dandridge was reduced to renting a room in the town of Pontotoc.

In 1913, he was granted a small soldier’s pension from the state. By this point Dandridge had moved to Randolph, Mississippi, where he rented a room from his son-in-law. The aging doctor applied for a pension increase two years later when he lost the use of his hands due to rheumatism he claimed to have acquired during the Civil War. In 1916, the Pontotoc County Pension Board granted Dandridge an annual pension of $125 for an irreducible hernia, but the next year the Mississippi State Pension Board reduced it to $75 per annum because it was not related to a wound suffered in combat.

Widowed, impoverished, and incapable of working as a physician, Dandridge was admitted as a resident of the Jefferson Davis Soldiers’ Home at Beauvoir. He lived there among his fellow veterans, their wives, and their widows until the end of his life. Powhatan Bolling Dandridge died at the home on February 13, 1919, and is buried in the Beauvoir Confederate Cemetery.

Lead author: Allan Branstiter, Southern Miss history doctoral candidate. Lead researcher: Robert Farrell, Southern Miss history MA student. Research also conducted by Southern Miss student Danielle Taylor.

]]>

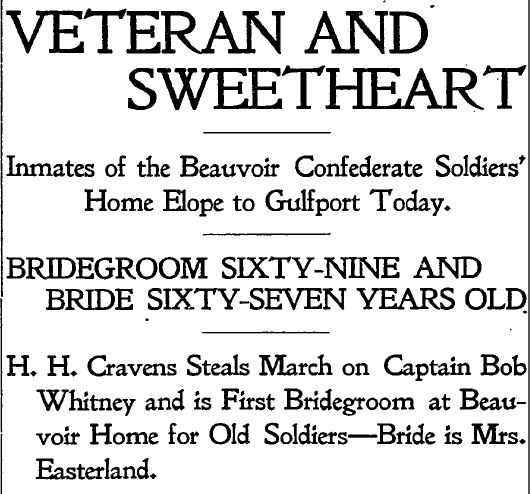

“The wedding to be has been the subject of a great deal of interested and sympathetic comment,” the paper explained, “but the elopement of the aged lovers, who are young in spirit if old in years, has aroused a whirlwind of surprise and interest whenever known.”

The soon-to-be Mr. and Mrs. Craven were no ordinary bride and groom; they were residents of the Beauvoir Veterans Home. Henry enlisted in the 42nd Mississippi Infantry in 1862, and served with the regiment until he was wounded and captured during Pickett’s Charge at the Battle of Gettysburg. After farming in Yalobusha, Jasper, and Leake Counties, Henry and his previous wife, Maggie, moved into Beauvoir on January 1, 1908. Sadly, Maggie died shortly afterwards of heart disease.

Mary Easterland was a native of Jones County, Mississippi, and she moved into the old soldier’s home on a widow’s pension on July 27, 1908. It was there that she met the recently widowed Henry Craven.

According to the home’s superintendent, John K. Mosby, the “Romeo and Juliet affair [had] been brewing for some months.” After learning of his wards’ plans from Reverend Finley, Mosby quietly converted a hospital room into a room for the newlyweds. “I am going to take care of my children to the best of my ability,” he told the Daily Herald, “so when I thought of this room I had it prepared for the returning lovers.”

The Cravens were only the first of several marriages between residents at Beauvoir. In fact, their “secret” nuptials preempted the wedding of Captain Robert Whitley and his fiance that had been scheduled on Christmas Day.

Henry and Mary Craven lived happily together at Beauvoir for the next five years, organizing charity events together and donating fifty dollars to erect a memorial to the women of the Confederacy. Henry died in 1914 and was survived by his wife.

Lead author: Allan Branstiter, Southern Miss history doctoral candidate. Research conducted by Southern Miss student Perre Carter.

]]>Stephen’s family navigated the boom-and-bust cycle of the cotton economy better than most, and his family’s wealth increased from $1,000 to $78,000 between during the 1850s. The Moore’s decorated their home with European furniture imported purchased from shops in Aberdeen’s extravagant Commerce Street and “Silk Stocking Avenue” (Franklin Street), like their wealthy neighbors who lived in the mansion and plantations that dotted Monroe County. While his older brother James had taken up cotton cultivation like their father, Stephen became an attorney in Aberdeen. Like many of Mississippi’s patricians, the Moore’s comfortable lives were built on the back of the forty-seven African-American men, women, and children they held in bondage.

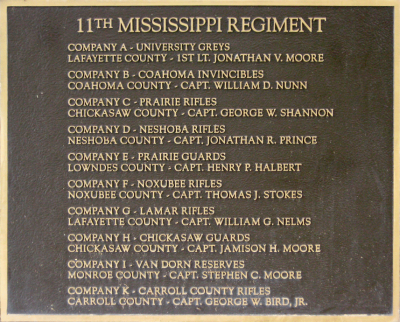

Considering their place among the cotton empire’s slaveholding elite, it should not come as a surprise to learn that the all three of the Moore brothers volunteered to fight on behalf of the Confederacy less than two weeks after the fall of Fort Sumter. James (26), Stephen (23), and Lucien Jr. (21) enlisted together as privates in Company I of the 11th Mississippi Volunteer Infantry Regiment on April 27, 1861. Like most of the men of their regiment—notably the University of Mississippi students who comprised much of Company A (“University Grays”) and Company G (“Lamar Rifles”)—the Moore brothers were much more affluent and better educated than the average Confederate soldier.

The men of 11th Mississippi were quickly transferred north and mustered into service in Lynchburg, Virginia, as part of General Joseph E. Johnston’s Army of the Shenandoah. The regiment was sent by train from Winchester, Virginia, to reinforce General P. G. T. Beauregard’s command during the First Battle of Manassas on July 21, 1861, but arrived too late to see combat. James Moore returned home to Monroe County shortly afterwards and enlisted in the 43rd Mississippi Infantry, while Stephen and Lucien Jr. remained with the 11th Mississippi and spent a miserable winter encamped near Dumfries, Virginia.

Less than a hundred miles north of the Moore plantation, Confederates under Generals Albert Sidney Johnston and Beauregard launched an attack against General Ulysses S. Grant’s army in the woods around Pittsburg Landing, Tennessee. Over the course of the next forty-eight hours over 23,000 soldiers were killed, wounded, captured, or went missing during the Battle of Shiloh. The bloodiest battle on American soil up to that point, Shiloh’s carnage shocked the divided nation and disproved predictions that secession would be a short and bloodless revolution. Like most Confederate regiments, the 11th Mississippi reenlisted for the duration of the war and held elections for officers after the Battle of Shiloh. In May 1862 the men of the regiment elected a new commander (the popular Colonel Philip Liddell), while Company I chose Stephen Moore to serve as a 1st Lieutenant.

It would not be long before Lt. Moore and his men would have their first real taste of combat. Less than month after Moore was commissioned, the 11th Mississippi was actively engaged in battle during the Peninsula Campaign. At the Battle of Seven Pines on May 31, 1862, the regiment’s 504 men charged an advancing line of Federal infantry during a poorly organized attempt to protect the Confederate Army’s left flank. Raked by musket and cannon fire, the regiment lost twenty killed and one hundred wounded. Among the day’s casualties was Lucien, Jr., who lost an arm and was evacuated to Chimborazo Hospital in Richmond.

After Seven Pines the army’s new commander, General Robert E. Lee, reassigned them to General “Stonewall” Jackson’s force in the Shenandoah Valley as part of a diversionary movement. Once the regiment arrived in the valley, they promptly turned around and marched secretly back to Lee’s position and attacked the Union General George B. McClellan’s right flank during the Battle of Gaines’s Mill.

Just after noon on June 27, 1862, General Lee launched a frontal attack against an elevated Union line protected behind entrenchments, trees, creeks, and swampy ground near Gaines’s Mill. Confederate losses mounted after repeated attacks faltered in the face of withering fire from the Yankee lines. General A. P. Hill’s division lost over a quarter of its men, and Lee himself joined in on the attack and urged his men to advance. Meanwhile, Jackson’s column (including Moore and his comrades) was delayed by poor directions and sniper fire as it slowly worked its way to the front. They arrived late in the day, weary after a day’s march, and prepared for another attack.

The four hundred men of the 11th Mississippi was part of Evander M. Law’s brigade when General Lee launched a massive attack along the entirety of the Union line at 7 o’clock that evening. Working in tandem with Hood’s Texas Brigade on its left, Law’s Brigade moved quickly and broke through the Union center. Exhausted and low on ammunition, the Union soldiers withdrew across the Chickahominy River and burned the bridges behind them. The 11th Mississippi suffered over 150 casualties—a loss of almost forty percent of its total strength—and did not see major action again for the rest of the campaign.

After General McClellan’s Army of the Potomac withdrew to Washington, DC, Lee sent Stonewall Jackson’s force north to intercept General John Pope’s Army of Virginia as it moved south against Richmond. Jackson deftly maneuvered his way behind the Union army and took a defensive position behind near Manassas on August 27, 1862. For his part, Pope believed he had caught the rebel army divided and launched an attack against Jackson on August 28. Often remembered for his offensive prowess, Jackson skillfully held back Pope’s forces for two days while Longstreet’s wing conducted a forced march to relieve his beleaguered soldiers.

Longstreet and the 11th Mississippi arrived on the field late during the second day of the Battle of Second Manassas and launched an attack against the Federal army’s flank the following day. Longstreet’s ability to control his corps was hindered as his men moved quickly over difficult terrain. As command and control broke down, the attack’s success would rely greatly upon the command initiative of brigade and regimental commanders as they proceeded forward. This was the case with the 11th Mississippi, which became separated from the rest of its brigade while it advanced across two miles of rugged woods, creeks, and ridges. Despite these challenges, the men of the 11th stayed together and performed well under the command of Colonel Liddell and officers like Lt. Moore. Longstreet’s assault ultimately stalled at dusk, but it was enough to convince Pope to withdraw his army from the field.

After the Battle of Second Manassas, General Lee marched his victorious army across the Potomac into Maryland as the Union armies regrouped under General McClellan in Washington. When McClellan intercepted papers indicating that Lee’s army would be temporarily divided while Jackson moved to seize Harper’s Ferry, he moved aggressively against Lee’s men near Sharpsburg, Maryland. During the night of September 16, 1862, the Federal army shelled the rebel line and mortally wounded Colonel Liddell. As the sun rose on what would become the bloodiest day on American soil, the 11th Mississippi would be without its beloved commander.

At about 5:30 a.m. on September 17, 1862, General Joseph Hooker’s Union corps attacked Stonewall Jackson’s men in a cornfield north of Sharpsburg. After a viciously fought stalemate that devolved into fierce hand-to-hand combat, the 11th Mississippi (now part of Hood’s Division) was ordered to counterattack through the West Woods near the Dunkard Church. Once in the cornfield, they engaged Union forces under General John Gibbon, which included the famously tenacious Iron Brigade. After losing half of their men as well as their battle flag, the 11th Mississippi retreated from the battlefield. When asked where his division was, Hood replied “Dead on the field.” Somehow, Lt. Moore emerged unscathed.

Constant campaigning and high combat losses took a heavy toll on the men of the 11th Mississippi. In November 1862, they were sent to Richmond and reorganized as part of a new brigade commanded by Jefferson Davis’s nephew, Joseph R. Davis. Major Francis M. Green of Oxford, Mississippi, was also appointed the regiment’s new commander and spent the winter of 1862-1863 recruiting new soldiers to fill out his unit.

The 11th Mississippi joined General Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia during the Gettysburg campaign, crossing the Potomac once again on June 25, 1863. Now promoted to Captain, Stephen Moore commanded Company I on July 3 when his regiment joined Pickett and Pettigrew’s assault on Cemetery Ridge during the Battle of Gettysburg. The 11th Mississippi briefly penetrated the Union line, but was repulsed after incurring 336 casualties (or eighty-seven percent of their men). Only forty of the regiment’s men emerged from the battle unscathed, while every soldier of Company A was wounded or killed. Captain Moore was wounded in the knee by an artillery shell during the attack, and eventually made his way back to Mississippi to recuperate.

Moore officially tendered his resignation as an officer in the 11th Mississippi on February 13, 1864. It is difficult to uncover Moore’s activities during the final year of the Civil War. A few days after he left the Army, Moore was apparently captured by Union soldiers back home in Aberdeen. However, on May 9, 1864, a letter states that rumors that the wounded captain was “resigned & disabled” were untrue, and that he was actively raising a new company of soldiers for the Confederate Army. While Moore’s service records ends in May 1864, he later testified that he surrendered in 1865 to the U.S. Army in Scooba, Mississippi—a fact that would place him among the few state militia soldiers remaining in rebellion during the final days of the Civil War.

Despite his wound, Moore remained active during Reconstruction. After returning to his parents’ home, he busied himself with managing the plantation alongside his mother. In October 1865, he attempted to raise a local militia company with Lucien J. Morgan (which is odd because records indicate the latter had been killed at Gettysburg). Despite the emancipation of their former slaves, the Moores remained as one of the wealthiest families in Monroe County according to the 1870 Federal Census.

Stephen never married. By 1880, he was 44 years old, apparently unemployed, and living with his brother James’s family. The 1900 Census lists him as a property lien clerk boarding with George and Zelda Bean of Okolona, Mississippi. When he eventually applied for a Confederate military pension, he was living on veteran’s land in Vicksburg and had no surviving relatives besides James’s daughters—Mary Green, Carrie Gillespie, and Margaret Fulton. Stephen Moore was awarded a pension on September 8, 1902, and moved to Beauvoir on December 2, 1905. He was remembered in his obituary as a man whose “brilliant mind and extensive reading . . . fund of natural wit, and wealth of anecdote and reminiscence, made him a rare companion.”

Lead author: Allan Branstiter, Southern Miss history doctoral candidate. Lead researcher: Southern Miss History major Armendia Hulsey. Research also conducted by Southern Miss student Kayla Sims.

]]>

The youngest of Ira Nash, Sr.’s boys, Ira Jr., was 18, still unmarried, and living at home when he enlisted, but the older sons, John and Charles, 30 and 29 respectively, left behind young families when they joined the Confederate Army. This included Charles’s wife Eliza, who remained at home raising two young daughters and an infant son.

In February 1862, Union forces under Ulysses S. Grant captured the Fort Henry and Fort Donelson in Tennessee, which forced Confederate General Albert Sidney Johnston’s forces to retreat southward and leave the Tennessee and Cumberland rivers in Yankee hands. For decades, southern planters had relied on these great waterways to send their crops to distant markets and their loss left the heart of the Deep South exposed to economic peril and large-scale invasions from the north. To counter this threat, the 5th Mississippi was transferred home in early 1862 and assigned to General James Chalmers’s Brigade in Johnston’s newly organized Army of the Mississippi. Gathering near Corinth, Mississippi, the Nash boys joined some 55,000 men hoping to stop Federal forces from capturing the city’s important rail-head.

On April 3, 1862, General Johnston moved his army—including the 5th Mississippi— quietly across the border and into Tennessee, where he hoped to catch the Yankees in camp with their forces divided. Although he planned to attack Grant on April 4, Johnston lost two days due to torrential rains that turned roads to mud and soaked his men’s gunpowder. His subordinate, Confederate General P.G.T. Beauregard, feared the initiative was lost when men started firing their muskets to test their powder (and possibly revealing their position to the enemy), and worried about the Union army’s possible numerical superiority. Beauregard urged Johnston to abort the assault and withdraw back to Corinth, but Johnston refused and declared that “I would fight them if they were a million.”

Despite Beauregard’s concerns, the Confederates had the advantage when the battle of Shiloh began on the morning of April 6, 1862. Federal commander Ulysses S. Grant had hoped to avoid any engagement until reinforcements arrived that would guarantee him a numerical advantage. Convinced rebels were preparing for a siege back in Corinth and hoping to avoid any interaction with Confederate patrols that would spark a fight, Grant did not order his men to build defensive entrenchments or deploy pickets to protect his camps. At about 5 a.m. a Union patrol encountered and engaged a force of Confederates in the woods south of Grant’s position, but no alarms were raised. A few hours later, as Union soldiers were preparing breakfast, startled deer burst forth from the wood line with the bulk of the Confederate infantry in hot pursuit. By 9 a.m. rebels were assaulting Union regiments all along the length of Grant’s line.

Albert Sidney Johnston’s battle plan was simple. He assigned each of his corps commanders a sector, with Leonidas Polk on the Confederate left and William J. Hardee on the right, Braxton Bragg in the center, and John Breckinridge in reserve. By strengthening his right flank with Breckinridge’s reserve corps, Johnston hoped to cut off the Yankee’s escape route and supply line on the Tennessee River. It was there, on the extreme right of the Confederate Army, where Chalmers’s brigade was located, including the 5th Mississippi and John and Ira Nash. Charles (as chance would have it) was not with his brothers at Shiloh, having returned home on leave a few weeks earlier to help his father with the family church. Moving forward across deep ravines, dense undergrowth, and muddy streams, Chalmer’s men (supported by artillery) attacked a startled Union brigade under the command of Colonel David Stuart at 7:30 a.m.

Stuart’s men held their position behind the lip of a steep ravine for over an hour until Chalmers’s men successfully punched a hole in the Union line. Under immense pressure from the rebel charge, Federals withdrew to a hill about 150 yards to their rear. Chalmers continued to advance, encountering four companies of Zouave skirmishers. They “secretly advanced close to our left,” Chalmers reported, and “fired upon the Fifty-second Tennessee regiment, which broke and fled in most shameful confusion.” Elements of the 52nd quickly regrouped and joined the ranks of the 5th Mississippi.

By the time Stuart got his brigade set in their new positions, he realized that his 800 men were now cut off from the rest of the army. On high ground protected by a fence and a stream, Stuart was determined to hold his position. Chalmers’s men deployed skirmishers and began to advance through an orchard in, according to their commander, “almost perfect order and splendid style.” Federals waited until Confederates came within about 40 yards of their line before unleashing a hellish volley that tore through the rebel line. It was in this engagement, at about 9:00 a.m., that Union gunfire struck Sgt. Ira Nash, Jr. in the forehead, killing him instantly. Nearby another bullet struck John Nash in the thigh. Chalmers reported that his men then surged forward and “after a hard fight drove the enemy from his concealment, though we suffered heavily in killed and wounded.” He later commended the 5th Mississippi and their commander, Colonel A. E. Fant, stating that “all the Mississippians, both officers and men, with a few exceptions . . . behaved well.”

The Battle of Shiloh devastated the Nash family. Ira, Jr., had been killed and John was in a hospital trying to survive a flesh wound that refused to heal. Later in July, their Unionist father appeared at the probate court in Philadelphia to collect the pay and bounties the Confederate government owed his dead son. In time, John would return home with a limp while Charles remained with the 5th Mississippi only until September 1862. Soon thereafter, Charles and Eliza welcomed a new son into the world and named him Ira Marion Nash II after their slain brother. While Charles later claimed that he was discharged due to a physical disability, his brother’s sacrifice may have also helped his commanders justify his discharge. It is also entirely possible that Charles had been sent home prior to Shiloh because of a physical disability.

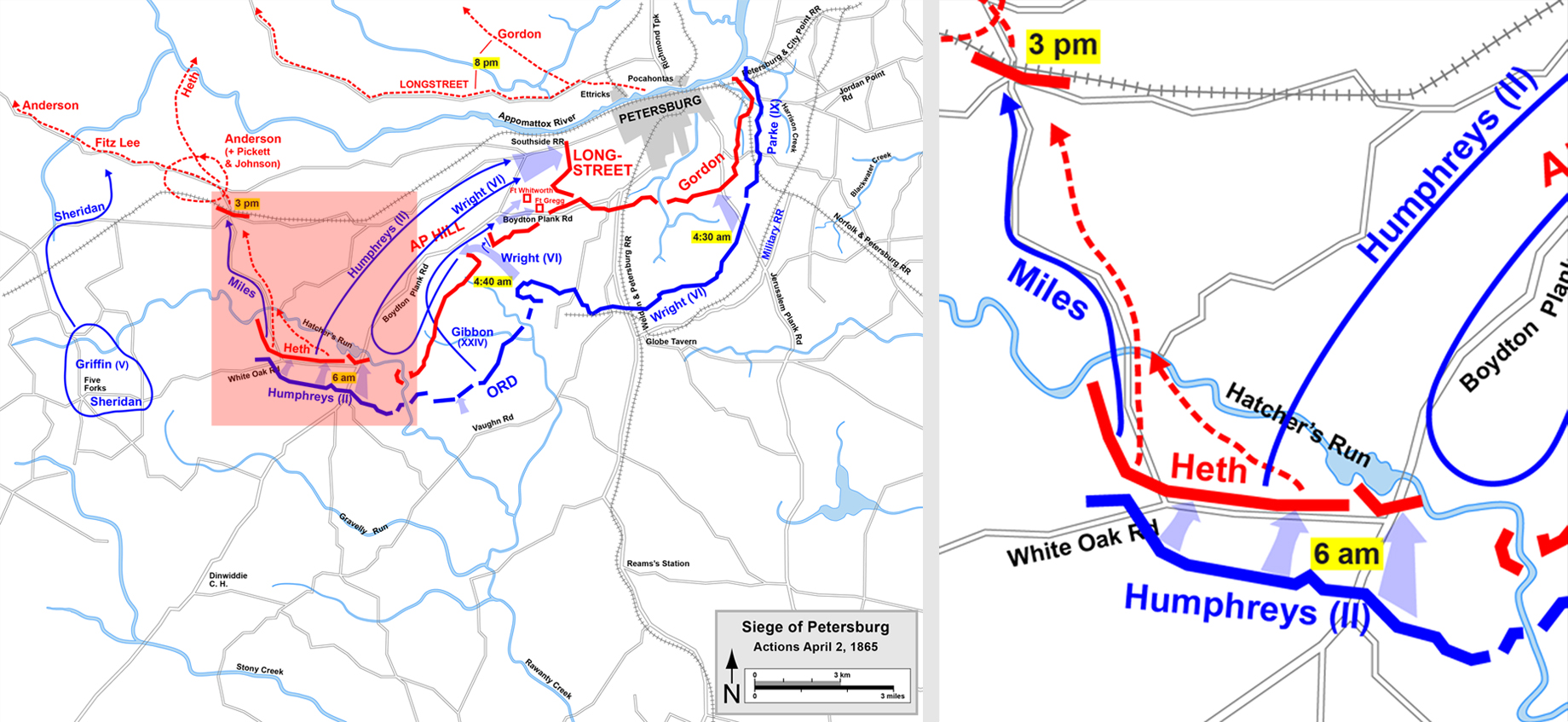

Charles Nash’s Civil War did not end in 1862. On November 21, 1864, he returned to military service by joining Co. D of the 11th Mississippi in General Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia. The 11th Mississippi was a hard-fighting combat unit that had participated in most of the major battles of the Eastern Theatre. By the spring of 1865, this once hale group of young men—drawn from lecture halls of the University of Mississippi and the cotton aristocracy—had been reduced to only 64 men commanded by Lt. Colonel George Shannon. When Charles Nash arrived in Virginia just before the Confederacy’s final spring, his new unit occupied the trenches southwest of Petersburg, Virginia, as part of General Henry Heth’s division.

On April 2, 1865, General Grant launched a large-scale attack against the rebel earthworks. Although the 11th Mississippi held their position, the thin line around them fractured under immense pressure from the Federal attack. General Heth ordered his men to retreat north, but the 11th was trapped by Hatcher’s Run, a wide stream swollen by recent rains, making it impossible to ford. A few of the men attempted to swim across and escape under a hail of rifle fire, but most of them surrendered. By nightfall, Richmond was abandoned and in the hands of Union soldiers, while what remained of the Confederate army retreated towards Appomattox Court House. In poor health after years of hard campaigning and months of siege combat, General Lee’s army laid down their arms on April 9, 1865. Having surrendered at Hatcher’s Run, the 11th remained in a prisoner of war camp in Point Lookout, Maryland, until they took the Oath of Allegiance to the Union en masse on June 29, 1865. Only then could they return to Mississippi.

After the collapse of the Confederacy, Charles Nash found work as a carpenter. While he would never match the wealth of his father, Charles seems to have found consistent employment building rail cars for the region’s expanding network of railroads. Every census between 1870 and 1910 shows Eliza and Charles living in a new place: Clarke County in 1870, Lafayette County in 1880, Washington County in 1890, with Ira II’s family in Colbert County Alabama in 1900, and finally at the Jefferson Davis Soldier Home at Beauvoir in 1910. No matter where he went, Charles relied on his skill as a carpenter to provide for his family, and he continued in this line of work into his late 60s.

After half a century together, Eliza passed away and Charles began to apply for a veteran’s pension in 1907. His mind and vision were clouded by the years, and he had difficulty recalling the details of his Civil War service. Embarrassed by his inability to answer the state’s questions, he scribbled an apology at bottom of his application: “I have forgotten some of the answers, my mind is not good, I can’t remember.” Regardless, the state had enough to verify that he had served honorably and was financially destitute. Charles Nash became a resident of Beauvoir three days before Christmas in 1909.

He seems to have enjoyed his life at the home, and Charles Nash was an active participant in the community’s social life. He participated in veterans’ reunions and donated $35 to a “Memorial to Women of the Confederacy” in Gulfport—an impressive sum considering the small amount of money he received as a pension. Charles Nash lived the rest of his life out on the shores of the Gulf of Mexico with his fellow comrades-at-arms. On August 11, 1913, just around supper, he passed away at the age of 83 years old, leaving “two sons and two daughters and many grandchildren to mourn his loss.” He was buried the next day in Beauvoir’s cemetery.

Special thanks to Mr. Len E. Reinker, a direct descendant of John J. N. Nash, for providing the BVP with information on the Nash family of Neshoba County. Please visit his website. Thanks, too, to BVP team members for their research on Charles Nash and family. Lead author: Allan Branstiter, Southern Miss history doctoral candidate. Lead researcher: Southern Miss History major Armendia Hulsey. Research also conducted by Southern Miss History major Hannah Smith.

]]>