One of the key factors that contributed to Beauvoir’s successful operations was the influence of the Tartt family. From 1916 through 1945, with the exception of only four years, Elnathan and Helen Tartt served as superintendent or assistant superintendent of the home. Their close supervision represented a New South bureaucratic efficiency that allowed for a constant level of care as well as key support from the state legislature and from the governor’s office.

Beauvoir Superintendents Elnathan and Helen Tartt, and their son Ned at Beauvoir. Either Elnathan or Helen Tartt served as superintendent of Beauvoir from 1916-1943 except for one four-year term from 1932-1936. Mississippi Gulf Coast Community College Beauvoir Collection.

Helen Tartt entered the role as assistant superintendent, to her husband Superintendent Elnathan Tartt, as early as 1916 (though she did not officially receive that title until 1920). In 1926, she accepted the governor’s appointment to run the home, a decade or more before it became common for white women to lead Confederate homes. Tartt reported to Beauvoir’s five-member all white board (which also included two women) and directly to Mississippi’s governor. They shared this role until 1928, when Elnathan Tartt resumed his role as superintendent and Helen as assistant superintendent. When political winds changed in the state in 1932, they were both replaced, but four years later, Helen Tartt resumed the leadership of Beauvoir, and she held the position of superintendent until her death in 1943.[1]

Throughout her leadership of the home, Helen Tartt managed large legislative appropriations and massive Depression-era cuts budgets with equal success. She directed the daily operations for as many as 250 residents and dozens of employees. She oversaw the physicians and hospital staff, the purchasing of food, livestock, and supplies, and managed all contract work for the property.[2] Her leadership came at a time of rising opportunity for white women in Mississippi. Women studied at institutions of higher education, entered the professional workforce, and assumed leadership roles at the state-funded women’s college, in the suffrage movement, in the arts and literature.[3]

On August 1, 1926, the New Orleans Times-Picayune featured Helen Tartt on its front-page coverage of leading white women in the region.

Helen Tartt’s early leadership may have been made possible by her husband’s success as a popular long-term superintendent, the experience she learned as assistant-superintendent to Elnathan, and his political connections to Governor Theodore Bilbo. Still, Helen gained recognition throughout the Gulf South, in her own right, for her advocacy of Beauvoir residents and the efficiency with which she ran the home.[4] The New Orleans Time-Picayune featured Tartt’s leadership of Beauvoir with a front-page article and photograph in 1926, insisting that it was a blend of her “good cheer, patience, housewifely and executive abilities” that “won for Mrs. Helen Tartt the only headship of a state institution in Mississippi.” The editor noted Elnathan’s prominence, but concluded that the board selected Helen “because of her eminent ability to handle this extremely difficult job.”[5] The public recognized Helen Tartt’s organizational acumen, too, if only through their regular contact with her as a prominent, influential business woman. From the late 1920s through the early 1940s, local papers printed frequent notices calling for bids from grocers, dairy farmers, undertakers, and contractors for services needed at the home, and readers were instructed to contact “Mrs. Helen Tartt, Supt.” with their sealed bids. These notices served as regular reminders, year after year, that a New South woman directed Beauvoir’s large-scale and efficiently run operations.[6]

Helen Tartt died in her leadership role at Beauvoir in April 1943. Elnathan accepted the role of superintendent for a short before resigning from the position later that summer.[7]

This post is excerpted from the

article by Susannah J. Ural, “‘Every

Comfort, Freedom and Liberty’:

A Case Study of Mississippi’s Confederate Home,” The Journal of the Civil War Era 9

(March 2019), 55-83.

[1] New Orleans Times-Picayune, August 1, 1926; Biloxi Daily Herald, April 2, 1943.

[2] Twelfth Biennial Report of the Board of Directors, Jefferson Davis Beauvoir Memorial Home, 1926-1927. Beauvoir, Soldiers Home Reports, Folder 1, Jefferson Davis Presidential Library, Biloxi, Mississippi.

[3] Marjorie Julian Spruill, “Nellie Nugent Somerville: Mississippi Reformer, Suffragist, and Politicians,” Joanne Varner Hawks, “Belle Kearney: Mississippi Gentlewoman and Slaveholder’s Daughter,” and Sarah Wilkerson-Freeman, “Pauline Van de Graaf Orr,” in Mississippi Women: Their Histories, Their Lives, eds. Martha H. Swain, Elizabeth Anne Payne, Marjorie Julian Spruill (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2010), 72.

[4] Praise for Elnathan Tartt, Helen Tartt, and the efficiency of the Jefferson Davis Soldiers’ Home appeared in dozens of papers from 1916 through the 1940s. Examples of this appear in the Daily Mississippi Clarion and Standard (Jackson, Mississippi), September 1, 1921; Biloxi Daily Herald (Biloxi, Mississippi), July 14, 1926; Greenwood Commonwealth (Greenwood, Mississippi), August 12, 1927; Indianola Enterprise (Indianola, Mississippi), September 29, 1927.

[5] New Orleans Times-Picayune, August 1, 1926.

[6] These ads appear regularly in the Biloxi Daily Herald from the late 1920s through the early 1940s. Specific examples can be found on May 14, 1927, July 3, 1936, and September 15, 1941. Thanks to Ward Calhoun, Carole Marshall, and Kathy Goss for their help in locating information on Helen Tartt.

[7] The Greenwood Commonwealth (Greenwood, Missisisppi), June 2, 1943.

]]>The Unusual Case of James Burney, Nathan Best, and Frank Childress

[This essay — revised for length — was taken from the article by Susannah J. Ural,

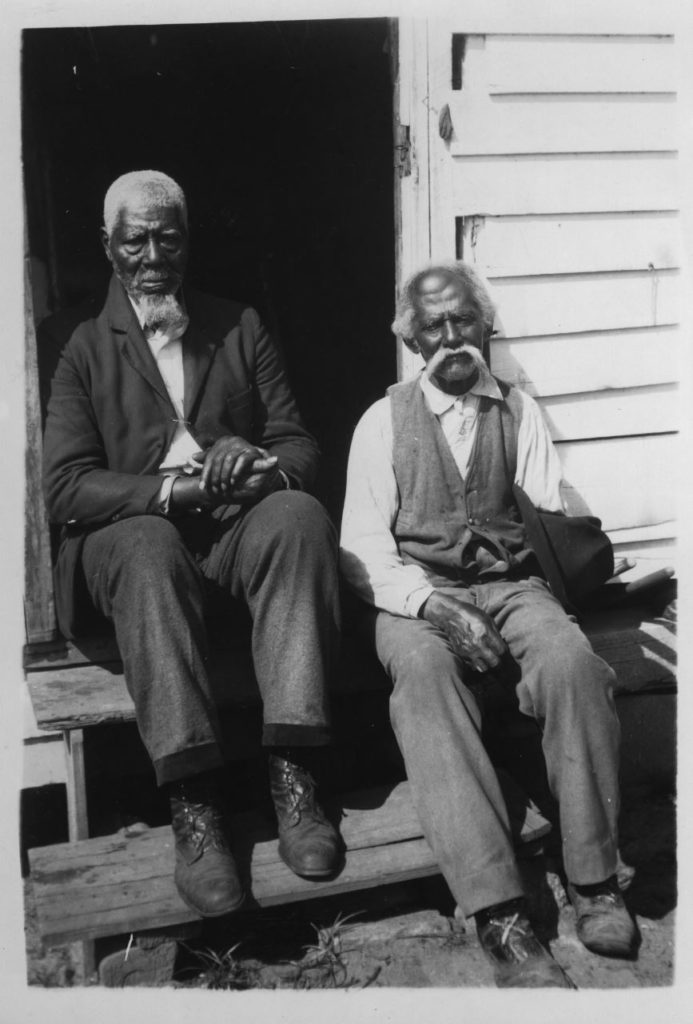

athan Best and Frank Childress, former Confederate body servants, Confederate pensioners, and residents of Beauvoir. Mississippi Gulf Coast Community College Dixie Press Collection

In the early 1930s, three aging, impoverished men entered the Jefferson Davis Soldiers’ Home in Biloxi, Mississippi. The facility, commonly known as Beauvoir, was Mississippi’s state home for destitute Confederate veterans and their wives or widows. Two of the men, Frank Childress and Nathan Best, bore clear signs of their wartime injuries. Childress suffered, he reported, from a “sore leg caused by a gunshot wound received during service in 1861.” Nathan Best’s empty sleeve spoke to his injury and amputation during the Petersburg Campaign. None of this made these men exceptional cases among Beauvoir residents except for one key factor. All three men — Childress, Best, and James Burney — had been enslaved Confederate body servants during the Civil War. This had made them eligible for a Mississippi Confederate pension funded by the state, and it also granted them access, or at the very least, consideration for access, to Beauvoir. They were also exceptional as the only African-American pensioners that the Beauvoir Veteran Project research team has been able to find living as residents (not employees) of a Confederate home.

Their admission was the result of an unusual pension policy that began in Mississippi in the late 1880s. When state legislators created the Mississippi’s Confederate pension policy in 1888, it provided modest financial support to Confederate veterans and their widows who had not remarried, as well as “the servants of the officers, soldiers and sailors of the late Confederate States of America, who enlisted from the State of Mississippi.”[1] It was not until the 1920s that five other states passed variations of this policy, joining Mississippi in providing pensions for formerly enslaved Confederate military “servants” or, in other states, laborers. Beyond being early, Mississippi’s policy was unique because legislators decided to pay African-American and white pensioners at the same rate. When Mississippi’s 1890 Constitution omitted reference to pensions for “servants,” state legislators took the time to clarify in 1896 that formerly enslaved men who had served Confederate soldiers could still receive state support. Legislators then took an even more unusual step in the Jim Crow South by insisting that veterans, widows, and “servants” would “share and share alike” from the state’s pension fund.[2]

They did this because in the eyes of white elites, many of whom were former slave owners, it allowed them to aid formerly enslaved men who had served the Confederate military effort in ways that whites saw as acceptable — as camp servants rather than as armed combatants.[3] Indeed, if Mississippi failed to do this, they fed the North’s narrative of the war. As one Mississippi editor explained, if Mississippi ignored such service, it “would mean that while negroes who rendered any military service for the Yankees are handsomely pensioned, those who served their masters in war adopted an evil policy and should be condemned.” Pensions for Confederate “servants” helped sustain the image of “loyal slaves” and similar aspects the Lost Cause memory of the war. [4] This argument swayed leading Mississippians until 1922, when a new generation rejected the idea of equal pensions regardless of race.[5] But this state endorsement was sufficient to warrant Frank Childress, James Burney, and Nathan Best the opportunity to apply for and gain admission as residents of Beauvoir.

In August 1930, a Harrison County pension board reviewed James Burney’s claim that he had served as Confederate President Jefferson Davis’s “

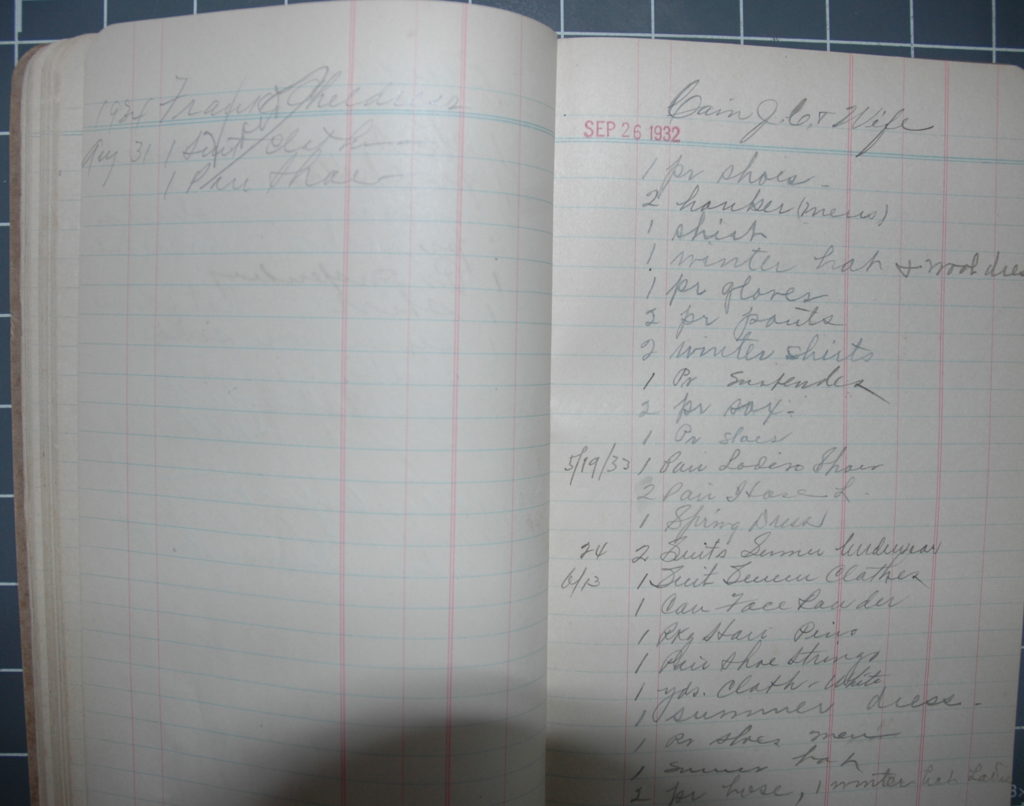

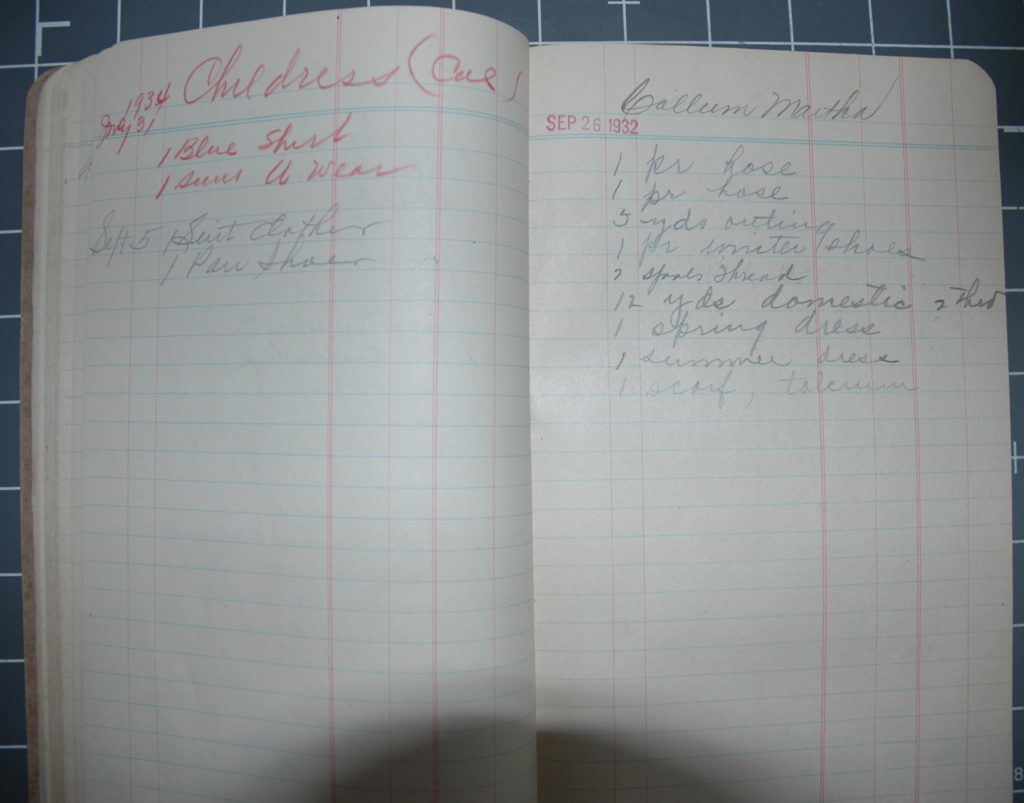

In August 1932, Frank Childress applied for a Confederate pension in Tunica County, Mississippi, where he explained that he had been a body servant to Colonel Mark Childress and suffered an 1861 gunshot wound to his leg. [insert image of Frank Childress pension app] The board approved his application in September 1932, but, like Burney, those funds, reduced on the grounds of race, were not sufficient to sustain Childress. He applied for residency at Beauvoir and arrived at the Jefferson Davis Soldiers’ Home in July 1934. A lack of sources prevents our knowing why Childress moved when he did, but he likely was motivated for the same reasons as many of the residents: at

Much more is known about the third African-American resident of Beauvoir, Nathan Best. [9] He entered the home with James Burney in August 1932, and later lived with Frank Childress. Childress and Best received the same $2 allowance as other residents, but their clothing allotment was less than that of white residents and their cabin was segregated from the cottage-like dormitories that housed white veterans, wives, and widows. Best explained, in the words of a 1930s Works Progress Administrative (WPA) interviewer, how he lived on this meager support: “I

Frank Childress clothing allotment. Beauvoir Ledger “Items Given to Inmates, 1932-1934” Housed at Jefferson Davis Presidential Library, Biloxi, Mississippi.

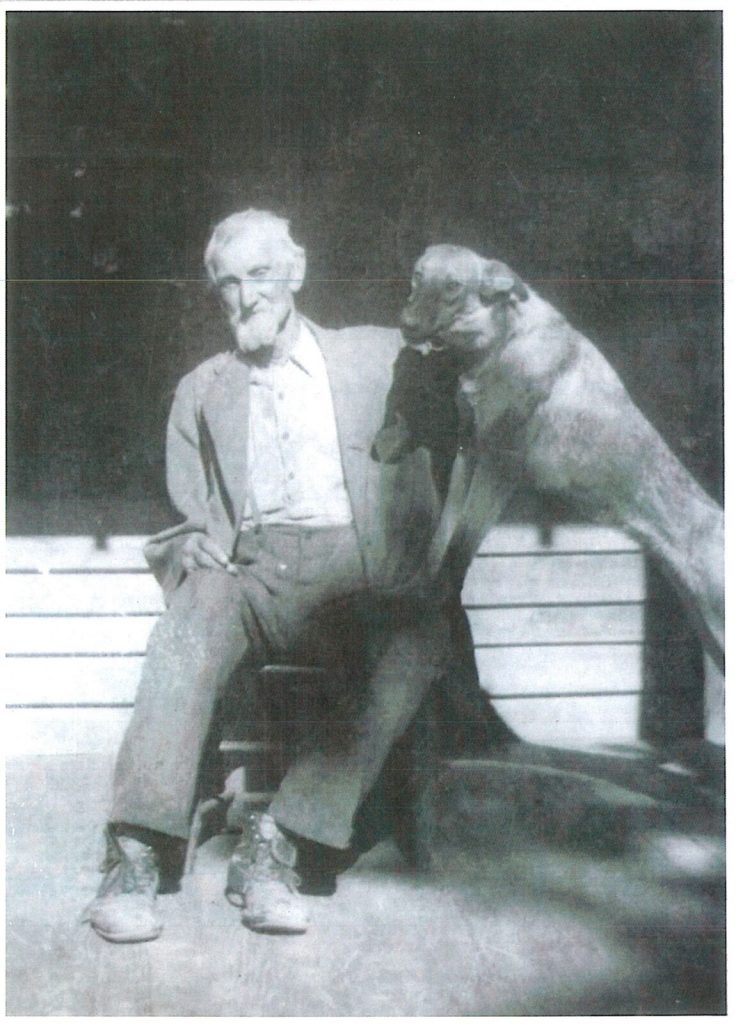

North Carolina-born Best was about sixteen years old when the Civil War began. He spent his youth enslaved in Snow Hill, North Carolina on the large Greene County plantation of Henry Best.[12] In 1863, Nathan Best went to war with his owner’s younger brother, Rufus Best. While carrying messages during the siege of Petersburg, Nathan Best’s horse fell and Best broke his arm so badly that it needed to be amputated. After the war Best returned to North Carolina where he worked as a farm laborer and married a freedwoman named Hester. He was an engaged voter and active in his community, but this enfranchisement ended abruptly when white North Carolinians “Redeemed” their state and the Klan threatened black North Carolinians who attempted to vote. The years after the war were good, he insisted, until then.[13]

Nathan Best worked in Greene County until 1880, when he and Hester and their three children moved to Wilson County, North Carolina, and then south to Georgia where Best worked in the turpentine industry, as he and his father had before the war. Hester died sometime before 1910, and Best married a woman named Nancy. By then the couple, and perhaps Best’s children, were living in Ocean Springs, Mississippi, a coastal town not far from Beauvoir, where Best made a living plowing small plots of land around town. Although neither could read or write, Nathan and Nancy Best owned their own home and clarified to the census enumerator in 1910 and again 1920 that they owned it mortgage free.[14] By the early 1930s an aging Nathan Best, now in his nineties and a widower — Nancy died in the 1920s — could not earn a sufficient living to sustain himself on a meager monthly pension.[15] He was admitted to Beauvoir and entered the home with James Burney on August 7, 1932.

Nathan Best and Frank Childress were featured in two newspaper and magazine accounts that emphasized their role as Confederate pensioners and residents, and they participated in ceremonies when prominent Americans — like Franklin Delano Roosevelt — visited Beauvoir. Writers highlighted Childress’s capture by Union forces and his admission that he later fought for the Union, but only because, the report claimed, he was forced to do so. A 1936 Mississippi Guide article included what was purported to be a direct quote from Childress himself: “

In a 1930s WPA interview conducted at Beauvoir, Nathan Best gave no indication of such dreams. When he talked about his life as a slave, he characterized his original owner, Henry Best and later his son, Bob, as “good” owners, but Best also described being hanged, whipped, and abused by an overseer on multiple occasions. If Best dreamed of anything in the future, it was leaving Beauvoir. While he liked things “pretty well here,” Best said he “would like it better ifn dey’d jes’ give me ‘nough pension, so I could live at home.”[17] It appears that Best got his wish in March 1939. He received an honorable discharge from Beauvoir and moved to his daughter’s home in Biloxi, and his Confederate pension benefits were reinstated one month later. Best died there in January 1940.[18]

Little

is known about the experiences of African-American residents of Confederate

homes. One scholar has argued that more black pensioners were admitted to

Southern homes as Confederate veterans died and the homes’ white populations

declined. It is not clear, however, that this practice extended beyond

Beauvoir.[19] In

1924, Kentucky’s Confederate home hired William Pete, a formerly enslaved Confederate

body servant, rather than admit him as a resident. The board felt compelled to

do something for Pete, who had been enslaved to Confederate General Joseph

Wheeler, but they refused to admit him as a resident.[20]

Mississippi chose another approach. Nathan Best, James Burney, and Frank Childress

were admitted to Beauvoir and received the same resident allowance, but they

received less clothing and lived in segregated quarters. Even in monthly

payment records and in the Jefferson Davis Soldiers’ Home Register, their names

appear at the back of the old bound volume.[21]

The public wrapped the men in the legend of the Lost Cause and blended their

wartime and postwar experiences into the myth of the happy slave. But James

Burney, Frank Childress, and Nathan Best — despite Klan violence, Jim Crow

bigotry, and reductions in their pensions — used a complicated Confederate

memory to secure shelter at Beauvoir when they had nowhere else to turn. Once there, they challenged residents’ and

visitors’ Confederate memories until Childress and Best’s families could help

them regain their independence with assistance from a Confederate pension.

Notes

[1] Journal of The Senate of the State of Mississippi at a Regular Session Thereof, Convened in the City of Jackson, January 3, 1888. (Jackson, MS: R. H. Henry, 1888), 333.

[2] Laws of the State of Mississippi Passed at Regular Session of the Mississippi Legislature Held in the City of Jackson, Commencing January 7, 1896, and Ending March 24, 1896 (Jackson, MS: Clarion-Ledger Company, 1896), 65; See also Foster, “‘To Mississippi, Alone,’” 34-37; Hollandsworth, Jr., “Looking For Bob,” 305; Dale Kretz, “Pensions and Protest: Former Slaves and the Reconstructed American State,” The Journal of the Civil War Era, 7: 3 (September 2017), 425-445.

[3] Mississippi only awarded pensions to formerly enslaved Confederate body servants. While some applicants referenced carrying dispatches or being wounded in pension applications, the state did not recognize them as combat soldiers. For a detailed analysis of this pension policy, see Hollandsworth “Looking For Bob.” For more on the Black Confederates debate, see Kevin Levin, “Myth of Black Confederates Won’t Go Away,” The Post and Courier (Charleston, South Carolina), October 11, 2017; Levin, “What Black Confederates Really Did During the Civil War” The Atlantic, February 21, 2012.

[4] The Lexington Progress Advertiser quoted in Jackson Daily News (Jackson, Mississippi), February 12, 1904; see a similar argument in Yazoo Herald (Yazoo, Mississippi), February 21, 1908.

[5] House Bill 382, Laws of the State of Mississippi Passed at Regular Session of the Mississippi Legislature Held in the City of Jackson, Commencing January 3, 1922, and Ending April 8, 1922 (Jackson, MS: Clarion-Ledger Company, 1896), 213-215. See examples of protest against this change see Natchez Democrat (Natchez, Mississippi), February 10, 1922 and February 14, 1922.

[6] Hollandsworth, “Looking for Bob,” 310-312.

[7] James Burney Pension Application, September 1, 1930 states that Burney worked for President Davis during the war as a body guard from April 4, 1863 through 1865. There is a letter supporting this claim from Sam Burney, for whom James Burney worked after the war. Burney’s August 1930 pension application makes the same claim. Beauvoir Veteran Project researchers investigated each resident in the sample to verify any reference to military service in the home register or in pension applications. To date no documenting evidence has been found in the Jefferson Davis papers or through inquiries to the National Civil War Museum to confirm or reject Burney’s testimony that he served as Jefferson Davis’s body guard. James Burney Pension Application, Harrison County, Mississippi. Mississippi Office of the State Auditor, Series 1201: Confederate Pension Applications, 1889-1932, Mississippi Department of Archives and History, Jackson, Mississippi; JDSH Register, 360.

[8] Frank Childress Pension Application, Tunica County, Mississippi. Mississippi Office of the State Auditor, Series 1201: Confederate Pension Applications, 1889-1932, Mississippi Department of Archives and History, Jackson, Mississippi; JDSH Register, 360. It is unknown if Childress returned to the care of family or was able to support himself. His daughter, Leloa Smith of Clarksdale, Mississippi, is listed as family in the Beauvoir Register, but the only notation about his departure is that Childress received an honorable discharge on December 28, 1936.

[9] Nathan Best’s name sometimes appears as Nathan Bess. “Bess” appears on one of his pension applications (March 1939), in the Biloxi City Directory in 1931, in the Beauvoir home register, in Beauvoir payroll records, and on the death certificate issued by the state of Mississippi. “Best” appears in his July 1930 pension application, in Harrison County Chancery Court records, in newspaper articles, in a WPA interview, and in correspondence from Beauvoir. I am using “Best” because the use of “Bess” in the home may have started with a misunderstanding or error during Best’s admission which throughout his time at the home and because this is the version of his surname recognized by a descendant and by historians. Special thanks to Jane Shambra, Charles Sullivan, and Deanne Stephens for helping me to unravel this mystery.

[10] Laws of the State of Mississippi Appropriations, General Legislation, and Resolutions Passed at the Regular Session of the Mississippi Legislature … 1932 (Meridian, Mississippi: Interstate Printers, Inc, 1932), 53-54; Laws of the State of Mississippi Appropriations, General Legislation, and Resolutions Passed at the Regular Session of the Mississippi Legislature … 1934 (Jackson, Mississippi: Tucker Printing House, 1934), 17.

[11] “Interview with Frank Childress and Nathan Best,” Folder: Interviews, War Related, Box 10700, Series 447, RG 60: Work Projects Administration, Mississippi Department of Archives and History, Jackson, Mississippi. Very few Beauvoir records exist for the 1930s – Board Meeting Minutes or Biennial Reports would have likely touched on any changes to allowances, but those records from the 1930s have not been found. A ledger listing what each resident was provided between 1930 and 1934 has been located, and verifies that Frank Childress and Nathan Best were provided notably fewer items than white residents. See untitled ledger listing items provided to residents, 1930-1934, Jefferson Davis Presidential Library, Biloxi, Mississippi.

[12] Henry Best died in 1860. His widow, Mariah Best’s, combined real and personal estate in 1860 was $100,000. See 1860 U.S. Federal Census, Tysons Marsh, Greene, North Carolina; Roll: M653_899; Page: 321; Family History Library Film: 803899; 1860 U.S. Federal Census – Slave Schedules. Digitized online, Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2010. Original source: United States of America, Bureau of the Census. Eighth Census of the United States, 1860. Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, 1860. M653, 1,438 rolls.

[13] See Nathan Best in 1870 U.S. Federal Census, Snow Hill, Greene, North Carolina; Roll: M593_1140; Page: 497AB; Family History Library Film: 552639. Rufus Best lists his combined personal and real wealth at $15,000 in the 1870 U.S. Federal Census, Olds, Greene, North Carolina; Roll: M593_1140; Page: 470B; Family History Library Film: 552639. Mariah Best has not been found in the 1870 Census, but by 1880 she was still listed as the head of her household. 1880 U.S. Federal Census, Snow Hill, Greene, North Carolina; Roll: 965; Family History Film: 1254965; Page: 67B; Enumeration District: 065; “Interview with Frank Childress and Nathan Best,” Folder: Interviews, War Related, Box 10700, Series 447, RG 60: Work Projects Administration, Mississippi Department of Archives and History, Jackson, Mississippi.

[14] 1910 U.S. Federal Census, Beat 4, Jackson County, Mississippi; Roll: T624_744; Page: 3A; Enumeration District: 0064; FHL microfilm: 1374757; 1920 U.S. Federal Census, Beat 5, Jackson County, Mississippi; Roll: T625_879; Page: 2B; Enumeration District: 70.

[15] Best’s age listed in the register when he entered the home in 1932 is 90. His death certificate indicates, however, that he was born in 1849, which would have made him 83. JDSH Register, 360. “Residents-Black Inmates” folder, Beauvoir, Soldiers Home Reports, Jefferson Davis Presidential Library, Biloxi, Mississippi.

[16] “Two Colored Veterans at Beauvoir One of Whom Served North as Well,” The Mississippi Guide, November 13, 1936. Transcription in Folder 12, Box 1, “Beauvoir,” Stevens Collection, McCain Archives, University of Southern Mississippi, Hattiesburg, Mississippi.

[17] Nathan Best interview, The Guide, November 13, 1936, Box 128J, Folder: “Racial Groups,” WPA Collection, Mississippi Department of Archives and History.

[18] Nathan Best, Confederate Pension, Form No. 5, Servant, Harrison County, Mississippi. Mississippi Office of the State Auditor, Series 1201: Confederate Pension Applications, 1889-1932, MDAH; Biloxi Daily Herald, January 18, 1940.

[19] Rosenburg, Living Monuments, 136.

[20] Williams, My Confederate Home,242.

[21] JDSH Register, 360.

]]>Over a three-year period, researchers at the University of Southern Mississippi studied the Jefferson Davis Soldiers’ Home in an effort to understand the experiences of the 1,845 men and women who lived there from 1903 through 1957. The team created a random representative ten-percent sample from a list of residents, and located more information about them in the original home Register. This included their date of admission, name, age, county of residence, and the military unit in which the veteran or the widow’s husband served. Death or discharge dates are usually included as well, and sometimes notations about residents’ re-entry, burial location, and family contact information are added. Researchers used this information to dig more deeply into each sample resident’s history through digitized census, military service, pension, and newspaper records. These sources offered insights into veterans’ and their families’ prewar and postwar wealth, slave holding status, educational levels, literacy rates, property ownership, wartime injuries, infant and adult mortality rates, and early-twentieth century financial stability. Supplementing all of this were surviving Beauvoir board meeting minutes and biennial reports, along with some hospital and supply ledgers, limited superintendent correspondence with residents and their families, and a few personal accounts from inmates, as they were known at the time.

Some of the key findings from this project include:

- Most white residents of Beauvoir enjoyed significant financial stability in their youths and into the twentieth century

- The majority of residents lived in upper-class households in 1860

- The average age of Beauvoir residents in 1860, when President Abraham Lincoln was elected and the first southern state seceded from the Union, was 16 years old.

- White prosperity faded significantly after the war, but the majority of Beauvoir residents still enjoyed middle-class status in their communities.[1]

- Residents may have been “the poorest of the poor,” as historians have described them, when they arrived at Beauvoir, but that misleading phrase ignores the benefits of wealth that many residents enjoyed as children and adults.

- The vast majority of residents described themselves as literate, and more than fifty percent had attended school.

- Home ownership records were only available for half of the sample, but among those residents, two-thirds owned their owned homes in 1900 and 1910, indicating, along with the other data, that many of Beauvoir’s residents enjoyed financial security through most of their lives.[2]

Beauvoir Veteran Project Complete Data File

List of Male and Female Residents at Beauvoir, 1903-1957

[1] “Middle class” is a term that can have diverse meanings in nineteenth-century America. The Beauvoir Veteran Project utilizes the financial class parameters for poor, middle, and upper class utilized by Joseph Glatthaar in Soldiering in the Army of Northern Virginia: A Statistical Portrait of the Troops Who Served under Robert E. Lee (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2011), 7. He defined the poorer economic class as having a combined wealth (real and personal property) as ranging from $0-$799, the middle class as $800 through $3,999, and the upper class ranging from $4000 or more. In 1860, residents lived in families that enjoyed an average household wealth of almost $12,000. In 1870, that wealth dropped to $1,100, but remained solidly middle class.

[2] Of those home-owners, nearly fifty-percent had paid off their mortgage.

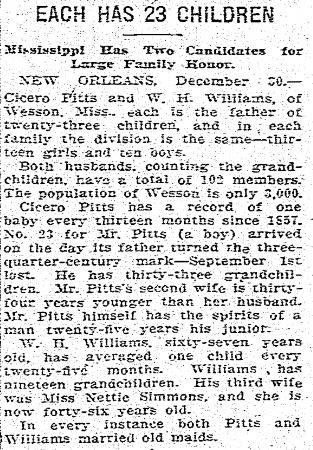

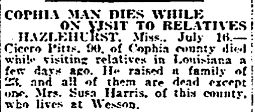

]]> In 1907, the Richmond Times Dispatch published an article about two men from Wesson, Mississippi, who claimed to be the fathers of twenty-three children each. One of these men was a former private in the 36th Mississippi Infantry named Cicero Pitts. He had fathered a baby, as the Time Dispatch noted, an average of once every thirteen months from his early twenties until he was seventy-five years old.

In 1907, the Richmond Times Dispatch published an article about two men from Wesson, Mississippi, who claimed to be the fathers of twenty-three children each. One of these men was a former private in the 36th Mississippi Infantry named Cicero Pitts. He had fathered a baby, as the Time Dispatch noted, an average of once every thirteen months from his early twenties until he was seventy-five years old.

Pitts was born in Georgia in 1833 before his family moved to Copiah County, Mississippi, where his parents (Wesley and Milly) established a plantation. He remained in Copiah after marrying his first wife, Matilda, who gave birth to their first child in 1859. According to the 1860 U.S. Census, Cicero Pitts’s estate was worth a respectable $1,280 and he also owned three slaves—a twenty-two year old woman, a two year-old boy, and a six-month old baby girl.

Like many men his age with families, Pitts did not enlist in the Confederate Army immediately after the Civil War started. Instead, he waited until May 2, 1862, when he enlisted for twelve months in Company E of the 36th Mississippi Infantry. Pitts and the 36th Mississippi spent much of the summer operating around Corinth, until September when they joined Major General Sterling Price’s army in Iuka as part of Colonel John D. Martin’s brigade.

Determined to prevent the Confederates from consolidating forces in Iuka, Mississippi, Major General Ulysses S. Grant ordered Major General William Rosecrans to drive away Price’s army of 3,179 men. On September 19, 1862, Rosecrans attacked the rebels two miles south of town around 4:30 pm. Forty-five minutes into the battle, the 36th Mississippi supported Brig. General Louis Hébert’s brigade as they counterattacked and temporarily captured a battery of Union artillery. Fierce fighting followed as the opposing forces alternated control of the field several times until a final bayonet charge by Martin’s brigade and the 36th Mississippi failed to drive the Federals back.

By the time Price withdrew his army from Iuka, twenty-two soldiers from the 36th Mississippi had been killed or wounded—including Cicero Pitts, who had been shot through both thighs and taken prisoner. The U.S. Army soon paroled Pitts, who returned home to recover from his wounds. Although the Confederate Army’s records do not mention his condition after October 1863, Pitts later stated on his pension application that he received a medical discharge due to the severity of his wounds. He had only been in the army for eight months.

Pitts remained in Copiah County after the war where he and Matilda farmed and raised their ever-increasing family. Matilda Pitts died sometime after 1880 and Cicero married Martha “Mattie” White, who was thirty-two years his junior. Many of Cicero Pitts’s children continued living on his farm as adults, and several of them worked at the textile mills in nearby Wesson.

Pitts moved into the Jefferson Davis Soldiers Home on March 22, 1920 when he was eighty-seven years old, but he was discharged the following May. He died on June 30, 1921 while visiting family in Allen Parish, Louisiana, where he is buried. Mattie Pitts lived until 1931, and she is buried in Copiah County.

Lead author: Allan Branstiter, Southern Miss history doctoral candidate. Lead researcher: Armendia Hulsey, Southern Miss history student.

]]>Not much is known about Peyton S. Webb’s time in the Confederate Army. He was only thirteen or fourteen years old when the war started, and he stated later in two pension applications that he enlisted in May 1864 as a private in Company E of the 4th Mississippi Infantry. Webb fought alongside the officers and men of Brig. General Claudius W. Sears’s brigade who broke through the Union line during the Battle of Franklin on November 30, 1864. A Confederate casualty report listed him among those wounded during the battle, but Webb stated on his applications that he was never injured. However, Webb and his service records do agree on how his war ended—he surrendered with his regiment in Blakely, Alabama on April 9, 1865 and spent a short time imprisoned on Ship Island and in Vicksburg, Mississippi.

Webb returned home, bought a farm near Winona, Mississippi, and married his first wife, Elizabeth Hill. Peyton and “Lizzie” had six children during their marriage, but only one (a daughter named Mattie) lived beyond 1900. Lizzie died in 1915 and Peyton remarried and began applying for a Confederate pension from the state a year later.

Webb and his second wife, Mary, were invited to live at the Jefferson Davis Soldier’s Home on May 1, 1929. Apparently it took some convincing on the part of the Beauvoir’s superintendent, Elthanan Tartt, to get the Webbs to accept the offer. Tartt assured them that while “some people who have never been here seem to think the place is a poor house . . . this is a mistake. Every comfort, freedom, and liberty is given [to] the inmate of the home.” Tartt invited the Webbs try living at Beauvoir knowing that if they did not like the place they could return to Winona.

Mr. and Mrs. Webb moved to the Jefferson Davis Soldiers’ Home the next year. Peyton kept in touch with his daughter and grandchildren through the mail. A few days before Christmas 1931, he wrote to Mattie that he was “all rite” and looking forward to the holidays, although he wished he could return home to celebrate. The staff was preparing for “a big Diner” hosted by United Daughters of the Confederacy, and he would try to buy a present the next time he was in Gulfport. He reminded Mattie how much he looked forward to mail, and urged his granddaughter to write him soon.

Peyton Webb lived on and off at Beauvoir during the early 1930s, reminding historians of the fluidity with which residents could enter and leave the home. He was honorably discharged for the final time in 1934, when he returned to Montgomery County until his death four years later. He is buried at the McKenzie Cemetery located between Duck Hill and Winona, Mississippi. Records do not indicate what happened to Mary Webb.

Lead author: Allan Branstiter, Southern Miss history doctoral candidate. Lead researcher: Lindsey Peterson, Southern Miss history doctoral student.

]]>The Anderson family owned no slaves, nor did they retain a large plantation or invest heavily in cotton production. Instead, they eked out a living practicing what historian Gavin Wright called “safety-first” farming. A poor yeoman-class family, the Andersons were primarily concerned with protecting their property. Land was the key to their sense of independence and social standing. Consequently, they avoided economic risks and speculating in commodity markets. Unlike the planters of cotton country, the Andersons focused on growing enough food to survive the year and only planted staple crops like cotton or tobacco if they had extra acreage and time. What cash they received in return for their staples on the market was used to buy luxuries and supplies they could not grow themselves.

When the Civil War began, Volney was only thirteen years old. His father attempted to enlist in the 27th Mississippi Infantry Regiment during the winter of 1861, but he was quickly discharged for unknown reasons. Volney enlisted with the 24th Mississippi Infantry under the command of General Edward C. Walthall on his sixteenth birthday, April 24, 1864. When he arrived in near Dalton, Georgia, young Private Anderson was greeted by a body of men hardened by years of difficult service on the battlefields of Perryville, Vicksburg, Murfreesboro, Chickamauga, Lookout Mountain. If Volney Anderson was hoping to prove his mettle in combat, he would soon have his chance.

Breaking camp on May 7, 1864, Anderson and 27th Mississippi marched to an entrenched position defending a hard angle on the left flank of John Bell Hood’s Corps at Resaca, Georgia. A week later, they repulsed two Federal charges and sustained heavy casualties. General Hood reported after the battle, “Walthall’s Brigade suffered severely from an enfilade fire of the enemy’s artillery, himself and men displaying conspicuous valor throughout under very adverse circumstances.”

Volney Anderson’s brigade had less than 500 men in the spring of 1864, and the next few months would be extremely costly of the men. The brigade lost fifty-one men at the Battle of Resaca on May 14; sixteen men at the Battle of New Hope Church on May 17; seventy-eight men at the Battled of Ezra Church on July 28; and forty-two men at the Battle of Jonesboro on August 30-31. According to family history, Anderson was grazed just above his ear by a bullet and survived the disastrous defense of Atlanta physically unscathed.

In October 1864, Anderson marched northwards with Hood’s Army and attacked the Union force under Major General John Schofield in Franklin, Tennessee. Hood ordered his men to advance across two miles of open ground (twice as much distance as traversed during Pickett’s Charge at Gettysburg) and attack an entrenched line of Union soldiers. The rebels managed to punch through the first line of Federal defenses, but bogged down when Northern reinforcements arrived. The 27th Mississippi (marching as part of General Stephen D. Lee’s corps) reinforced Hood’s wavering left flank, but the Confederate Army was driven back after sustaining almost 7,000 casualties. Volney Anderson’s brigade lost 76 men killed and 140 wounded. After another costly defeat at the Battle of Nashville, he and what was left of Hood’s Army retreated across the Tennessee River and into Mississippi.

After establishing winter quarters near Tupelo, Anderson and his brigade were granted furloughs until they were ordered to regroup in Meridian on February 14, 1865. Once assembled, Anderson and the remaining 282 men in his brigade made for the Carolinas, where the surrendered with General Joseph Johnston’s army on April 26—two days after Volney Anderson’s seventeenth birthday.

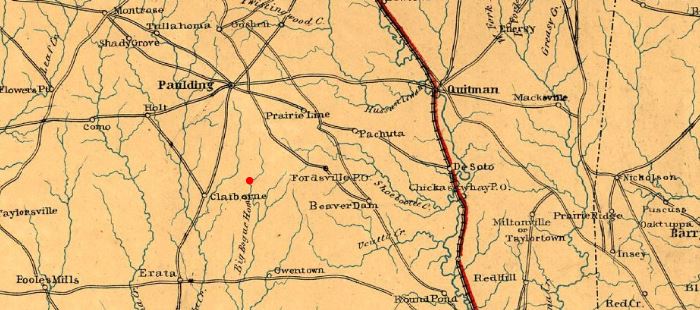

Private Anderson returned to his family’s farm in Heidelberg after the war. On September 3, 1873, he married Nancy McCraney. She was raised in the nearby town of Claiborne by her oldest sister and her husband (Flora and John B. McFarland) after her parents died. Volney and Nancy Anderson had ten children during their 66 year marriage.

In 1881, the Andersons relocated to a burgeoning Pine Belt lumber and railroad hub. Their new town was incorporated and named Hattiesburg, Mississippi the following year. The Andersons were also founding members of First Presbyterian Church. They also sold the timber they grew in plots in nearby Petal and Oak Grove and eventually and became one of the most prominent families in town.

Volney Anderson stopped working sometime after 1910 due to his age. He applied for a Confederate soldier’s pension in 1916 and lived on his farm until he was admitted to the Jefferson Davis Soldiers’ Home in Biloxi on August 9, 1923 (Nancy Anderson was admitted the following October).

They seemed to have enjoyed their time at Beauvoir. Anderson descendants recall Volney enjoying telling guests about his time in the army, and that he once sounded off with a rebel yell when President Franklin D. Roosevelt visited the home in the 1930s. Anderson also told a local paper about a slave who accompanied his company during the war and washed the soldiers’ clothes until an officer “stole” the man. When his grandchildren asked him if he had ever killed a man, Volney stated “I don’t know. But I know that men fell where I was shooting.”

His daughter Bertha, recalls a story her father told about the time he and some men separated from their unit and ran out of food. After traveling a bit and avoiding Union patrols, the starving men came across a farm and stole a goose they found there. Worried that a fire would alert Union patrols of their location, Anderson and his friends snuck into the woods and ate the creature nearly raw. The men inevitably became ill, and Bertha said her father never let his family keep geese on their farm.

The Andersons lived together at Beauvoir until Volney’s death on December 15, 1938 and the age of 91. The funeral was held at First Presbyterian Church in Gulfport, where the pastor read Alfred Lloyd Tennyson’s poem “Crossing of the Bar.” Nancy Anderson died at the home in 1945. Although one of their grandchildren had died in a Japanese prisoner of war camp in the Philippines, the Andersons were survive by ten children, 52 grandchildren, and 42 great-grandchildren. Both Nancy and Volney Anderson are buried at Beauvoir.

Lead author: Allan Branstiter, Southern Miss history doctoral candidate. Research also conducted by Rachael Pace, Southern Miss history student.

]]>

When the Civil War began, James Everett was a twenty-nine-year-old overseer on his family’s plantation. Of the five sons born to the Everett clan, four would serve in the Confederate Army. During the heady days of April 1861, James Everett married Sarah Elizabeth Garner and enlisted in the 22nd Mississippi Infantry; however, he was medically discharged the following October when it became apparent he had asthma.

In 1862, James reenlisted in the army. This time he signed up to serve alongside his brothers Alexander (30) and Charles (16). The Everetts were assigned to Company I of the 4th Mississippi Cavalry, which was comprised of men from Amite, Wilkinson, Pike, and Franklin counties. The brothers fought side by side during skirmishes around Port Hudson and against General William T. Sherman’s march from Vicksburg to Meridian.

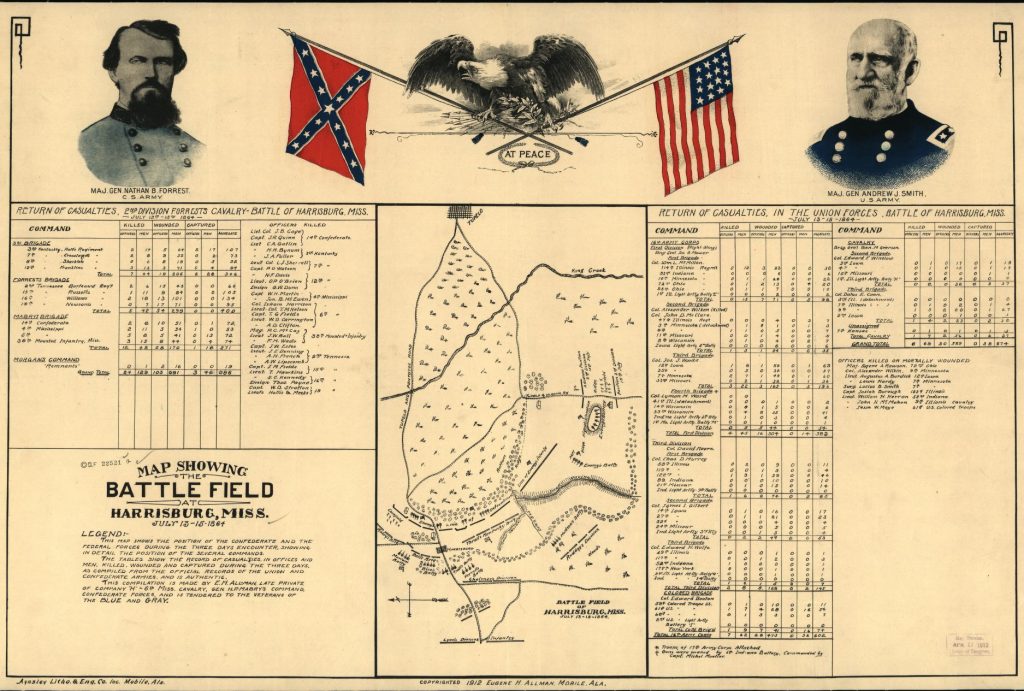

At some point during the fighting in northern Mississippi in late 1863 and early 1864, Marshall Everett joined his older brothers and the 4th Mississippi Cavalry. Since the seventeen-year-old Marshall does not have his own service record, he may have never officially enlisted in the Confederate army. Nevertheless, the young man accompanied his brothers to Harrisburg, Mississippi, where they attacked the U.S. Army’s fortified line south of the city on July 14, 1864. The uncoordinated rebel assault was ultimately repulsed and six men of the 4th Mississippi were killed that morning. Among the dead was Marshall Everett, whose body was returned to Amite County and buried in the family cemetery.

The remaining Everett men remained with their regiment until the end of the war. On November 4-5, 1864, they were part of General Nathan Bedford Forrest’s successful raid of a U.S. supply depot in Johnsonville, Tennessee. The attack destroyed millions of dollars worth of equiptment, including four gunboats, fourteen transport vessels, twenty barges, and twenty-six artillery pieces. Eventually, the men surrendered with their command in Gainesville, Alabama, on May 12, 1865.

After the war, James Everett returned to his wife and young daughter (Lula) and began farming in Amite County. Like much of the slaveholding class, the Everetts’s experienced significant financial losses due to the abolition of slavery and sinking cotton prices. By 1870, the combined value of the family’s holdings totaled up to $3,824—over $38,000 less than what they had a decade before. Still, they enjoyed a level of wealth that was significantly higher than many of their neighbors.

James Everett remained in the county until his wife’s death in 1889. Then sixty-nine years old and unable to work, he moved into his brother-in-law’s home in Little Springs, Mississippi and applied for a Confederate veteran’s pension. Citing the case of asthma he contracted while in the infantry in 1861, the state offered him $25 a year.

In 1899, Amite County Sherriff J. B. Turnipseed auctioned off the James Everett’s property to pay for delinquent taxes, and the state approved his second pension application for $780 per annum in 1900. Everett moved into the Jefferson Davis Soldiers’ Home at Beauvoir on January 14, 1907, and lived there until he died twelve years later. He is buried on the grounds of the home.

Lead author: Allan Branstiter, Southern Miss history doctoral candidate. Lead researcher: Southern Miss History major Rebecca Applewhite.

]]>Three of the Coker men served in the Confederate Army during the Civil War. Elder brothers Aleazer and John, enlisted with the 7th Mississippi Infantry in September, 1861. Shade Coker—then seventeen years old—enlisted with Garland’s Battalion of militia cavalry on August 8, 1862, possibly seeking militia service in the hope that this would let him remain home to help with family. Although he enlisted for a three-year term, Shade only remained with his militia unit until April 30, 1863. It is unclear why he left, but it is possible that his brothers may have had something to do with his decision.

On September 14, 1862, Aleazer and John participated in General James R. Chalmers’s poorly planned assault on Union fortifications outside Munfordville, Kentucky. John was struck by a blast of grapeshot and both brothers were captured when Chalmer’s withdrew. They were sent briefly to the Union prison in Cairo, Illinois, before they were exchanged and sent back to the rebel army. Instead, John Coker returned to Pike County without permission. His brother Aleazer returned to the 7th Mississippi Infantry and served with distinction at the Battle of Stone’s River, where his bravery won him a place on the Confederate Roll of Honor—however, he also deserted from the army and returned home by late 1862 or early 1863.

All three of the Coker brothers had abandoned Confederate military service by the time Ulysses S. Grant’s Union army invaded Mississippi during the spring of 1863. Discontent with the Confederate government was growing on the Mississippi home front and hundreds of deserters took to the hills, woods, and swamps. John Coker’s wound was probably reason enough for conscription agents to leave him alone, but Confederate authorities issued a warrant for Aleazer’s arrest during the winter of 1863-1864. Only Shade Coker returned to the army when he served as a teamster from August 1 to September 30, 1864 with the 38th Mississippi Cavalry.

After the war ended, the Coker brothers remained close to home. Sometime before 1870, Shade married a widow name Mary Malinda Collins (née Price) and became a tenant farmer near Brookhaven, Mississippi, where they raised her children and had children of their own. The Cokers would not stay in Brookhaven long, as Shade began looking for opportunities in the burgeoning industrial sector in nearby Wesson.

When the Cokers moved to Wesson it was home to the Mississippi Manufacturing Company (renamed Mississippi Mills in 1873) and a rapidly expanding factory town. The textile mill was built in 1866 by James Madison Wesson and sold to William Oliver and John T. Hardy after it went bankrupt in 1871. After the mill burned down two years later, Hardy convinced Edmund Richardson, one of the richest men in Mississippi, to become a partner and finance the construction of a more modern facility. Richardson soon bought out Hardy and—with Oliver acting as general manager—built four large mill complexes in Wesson between 1873 and 1894.

Life in Wesson was dominated by Mississippi Mills. A strict prohibitionist, James Madison Wesson made sure that the southern border of dry Copiah County jutted far enough south to include his factory. Fueled by the jobs provided by the mill, Wesson’s population skyrocketed from 464 residents in 1870 to 3,168 residents by 1890. Electric lights were installed in the factory in 1882, allowing textile production to continue into the evening. By the 1890s, the mill employed 1,200 workers who produced 4 million yards of cotton goods, 2 million yards of wool, and 320,000 pounds of yarn and twine annually.

Among the people employed at Mississippi Mills in 1880 were Shade Coker and three of his children, Augusta (23), Eugene (18), and Zeno (12). On February 28, 1897, his wife Malinda died and was buried in her parent’s family plot in Bogue Chitto, Louisiana. A year later, Shade Coker married his second wife, Bettie (who was thirty years his junior), and began renting a home apart from his children. In 1900, Shade Coker was still working at the mill, while his children lived in the home owned by his eldest step-daughter, Augusta.

According to the 1910 Census, Shade and Bettie Coker purchased a farm in Brookhaven while his children remained in Wesson. In 1906, Mississippi Mills was forced into receivership having never recovered fully from the death of Edmund Richardson and the Panic of 1893. As a result, only one of the Coker children (Sallie, 39) still worked at the mill, while Augusta took care of the household work and Willie (at 37, the youngest of Shade and Malinda Coker’s children ) sold gum on the street.

Shade and Bettie Coker were fixtures in the social life of their community at the turn of the twentieth century. In 1909, Bettie judged a baby show at the Lincoln County Fair, while Shade became an active figure in local veterans affairs. The Cokers appear to have lost a significant amount of their savings in 1914 when the Commercial Bank and Trust of Brookhaven failed, but they retained control of their dairy farm until at least 1920.

In 1923, Shade and Bettie sold their forty-acre dairy farm and moved into the Jefferson Davis Soldiers’ Home. After a brief stay at Beauvoir, they removed for unknown reasons to Sheffield, Alabama, where Shade died of pneumonia soon thereafter on April 16, 1924. Only 45 year old, Bettie relocated to Hot Springs, Arkansas and finally New Orleans, where she passed away on May 23, 1938. The Brookhaven Country Club now stands on the land once occupied by the Shade Coker farm.

Lead author: Allan Branstiter, Southern Miss history doctoral candidate. Lead researcher: Robert Farrell, Southern Miss MA history student.

]]>

The realities of camp life took their toll on the Walker brothers. Army records state that John contracted one of the many camp illnesses even before leaving Mississippi. Conditions worsened when the 16th Mississippi arrived in Virginia and set up camp next to a North Carolina regiment suffering from a measles outbreak. Despite relocating to a new camp near Centreville, Anderson Walker contracted typhoid fever and died on September 19, 1861. Winter offered no respite to young John, and he was hospitalized again for an unnamed illness in January-February 1862.

Private Walker rejoined his regiment in time to participate in General Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson’s Valley Campaign. After fighting with Jackson’s Army of the Valley at the battles of Winchester and Cross Keys, the 16th Mississippi marched east towards Richmond in time to confront Major General George B. McClellan’s army during the Seven Days Battles. The regiment was then transferred to Brig. General Winfield S. Featherston’s brigade. Despite the fact that he and his division were held in reserve during the final Confederate attack at the Battle of Second Manassas, John Walker sustained a serious wound on August 30, 1862.

Confederate records indicate that Walker spent five months recovering from vulnus sclopeticum—a gunshot wound—before returning to his unit on February 23, 1863. He and the rest of 16th Mississippi fought at Chancellorsville (suffering seventy-six casualties) and Gettysburg, where they lost nineteen men during a disjointed attack on the Union line on Cemetery Ridge on July 2, 1863.

The 16th Mississippi did not see significant combat again until May 1864, when they fought at the battles of the Wilderness and Spotsylvania Court House. Walker suffered another wound during the fighting around Cold Harbor on June 6 and was promoted to corporal after reuniting with his regiment just over a month later. He fought at one more battle—the Battle of Weldon Railroad, also known as the Battle of Globe Tavern—where Union soldiers captured Walker during a reckless attack on entrenched Federal artillery on August 21.

Walker arrived at the Federal prisoner of war camp at Point Lookout, Maryland on August 24 and remained there until he was paroled on March 14, 1865. According to an early biographer, Walker attended a school organized by prisoners at Paint Lookout.

After the war, Walker returned to Pike County, engaged in planting, and married Mary Jane “Molly” Magee, the daughter of a wealthy former slaveholder. In 1872, he established a general merchandise store that boasted $75,000 in annual sales by the 1880s. Molly and John named their first son Jefferson Davis Walker and adopted a boy named Oscar Alford in 1874. Neither of their sons survived past 1907.

In 1873, John helped his father-in-law, Obed Magee, transfer land to the Magee’s former slaves after a suspicious fire destroyed their church—now known as Rose Hill Missionary Baptist Church in Magnolia, Mississippi. Local family history also states that Molly Magee Walker was close to a half-sister named Elva (or Elvie) that her father had with an enslaved woman named Rachel.

John Walker was elected to the Pike County Board of Supervisors for eight consecutive years and represented the county in the legislature for one term as a member of the Democratic Party during the 1880s. He also served as a justice of the peace for a number of years. The first iron bridge across the Bogue Chitto River was also named after him.

Walker maintained a farm in Pike County until around 1910, when the U.S. Census listed him as a boarding house keeper. Mollie died two years later and is buried in the Magee family cemetery near Magnolia. According to the 1920 Census, Walker lived in the home of Eugene P. Magee—Molly’s nephew—in Laurel, Mississippi. Two years later, in June 1922, John Walker was admitted into the Jefferson Davis Soldier Home, and he lived there until his death on October 19, 1923. He is buried in Magee, Mississippi.

Lead author: Allan Branstiter, Southern Miss history doctoral candidate. Lead researcher: Lindsey Peterson, Southern Miss history doctoral student.

]]>When Thomas Dandridge died in 1842, he had saved enough money to leave each one of his children $440 in land (about $11,116 in 2016). He also left the control of the plantation and eight slaves to his widow, who continued to manage the estate while seeing to her children’s’ education. By 1860, the Dandridge’s land and twenty-four slaves were valued at $32,000 (about $867,715 in 2016).

Powhatan Bolling Dandridge attended the University of Mississippi during the late 1850s before moving on to the Medical College of South Carolina in Charleston (now the Medical University of South Carolina). In 1860, he wrote a thesis investigating malarial fever, earned his MD, and returned to Mississippi to live with his mother and practice medicine.

In 1862, Dr. Dandridge was appointed as the surgeon of the 3rd Mississippi Cavalry, a state militia unit originally organized to serve as minute men. Throughout the winter of 1862 and summer of 1863, the regiment operated locally to counter Union raiding across the Tennessee border. From mid-to-late June 1863, the 3rd Mississippi Cavalry supported the Confederate effort to defend Vicksburg, though they were not captured when the city fell to Union control in July. In August, General James R. Chalmers ordered the regiment to locate and arrest Confederate deserters and conscripts in the state.

After Chalmers was forced to abandon his headquarters in Grenada, Mississippi, the 3rd Mississippi Cavalry and Dr. Dandridge regrouped in Abbeville and attempted to raid William T. Sherman’s supply line in Collierville, Tennessee in October 1863. Although they were able to capture or destroy a significant amount of Union supplies south of Memphis (including General William Tecumseh Sherman’s horse, Dolly), the rebels were ultimately forced to withdraw back to Mississippi. On February 22, 1864, the 3rd Mississippi Cavalry participated in General Nathan Bedford Forrest’s defeat of General Sooy Smith’s expedition at the Battle of Okolana.

On January 6, 1864, General Chalmers (who usually disdained militia units) praised the professionalism and fighting ability of the 3rd Mississippi Cavalry and urged the Confederate Government to enlist the regiment into regular service, which they did. Dr. Dandridge was not among the men who wanted to be folded into the Confederacy’s regular army, however, and he transferred to the 7th Mississippi Cavalry (also known as the 1st Partisan Rangers) instead of accompanying the 3rd Mississippi Cavalry to Georgia in July 1864. Dandridge remained with the 7th Mississippi Cavalry until the end of the war and surrendered at Selma, Alabama on May 4, 1865.

Dandridge began courting Sylvia Lyon, the daughter of a very wealthy planter from Chickasaw County, when he returned home from the war. The pair married in 1866 and had a daughter, Virginia Louise Dandridge, on May 18, 1867. Like many of Mississippi’s former slaveholders, the Dandridges lost an immense amount of wealth after the Civil War. Dr. Dandridge owned real estate in Ellistown, Mississippi valued at just $20 in 1870. He did, however, own $2,000 in personal property, most likely materials associated with his medical practice.

In 1880, Dr. Dandridge had moved his medical practice to nearby Union County, Mississippi. Four years later his daughter married a local farmer named George Lacy Hall and gave birth to a son in 1893. She continued to live in the area until her death in 1939.

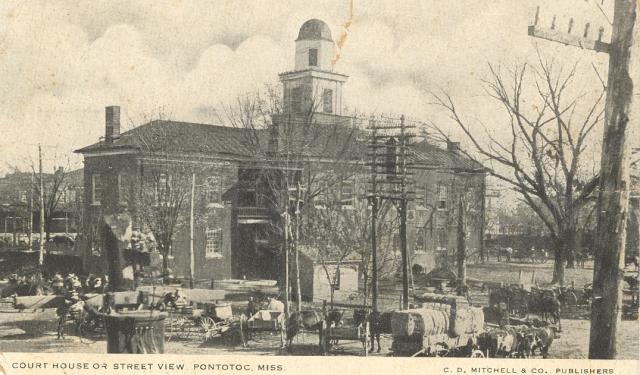

Like many veterans before the widespread use of pensions and social security, Dr. Dandridge struggled to make ends meet as he grew older and less capable of earning an income. His wife, Silvia Dandridge, died sometime after 1880 and by 1900, Dr. Dandridge was reduced to renting a room in the town of Pontotoc.

In 1913, he was granted a small soldier’s pension from the state. By this point Dandridge had moved to Randolph, Mississippi, where he rented a room from his son-in-law. The aging doctor applied for a pension increase two years later when he lost the use of his hands due to rheumatism he claimed to have acquired during the Civil War. In 1916, the Pontotoc County Pension Board granted Dandridge an annual pension of $125 for an irreducible hernia, but the next year the Mississippi State Pension Board reduced it to $75 per annum because it was not related to a wound suffered in combat.

Widowed, impoverished, and incapable of working as a physician, Dandridge was admitted as a resident of the Jefferson Davis Soldiers’ Home at Beauvoir. He lived there among his fellow veterans, their wives, and their widows until the end of his life. Powhatan Bolling Dandridge died at the home on February 13, 1919, and is buried in the Beauvoir Confederate Cemetery.

Lead author: Allan Branstiter, Southern Miss history doctoral candidate. Lead researcher: Robert Farrell, Southern Miss history MA student. Research also conducted by Southern Miss student Danielle Taylor.

]]>