Three African-American Residents at Beauvoir:

The Unusual Case of James Burney, Nathan Best, and Frank Childress

[This essay — revised for length — was taken from the article by Susannah J. Ural,

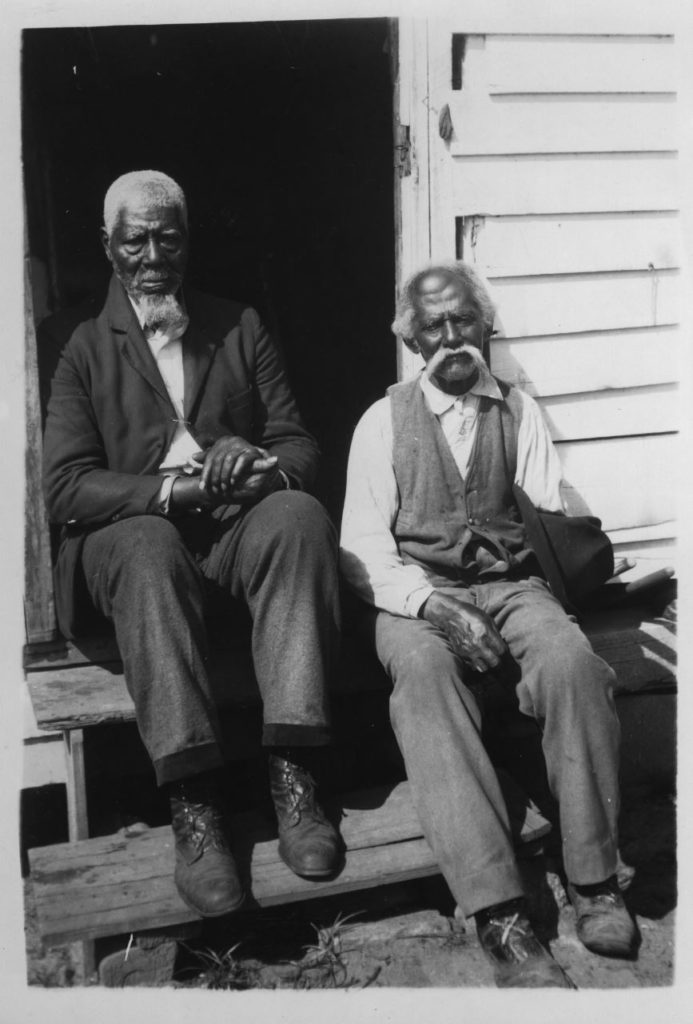

athan Best and Frank Childress, former Confederate body servants, Confederate pensioners, and residents of Beauvoir. Mississippi Gulf Coast Community College Dixie Press Collection

In the early 1930s, three aging, impoverished men entered the Jefferson Davis Soldiers’ Home in Biloxi, Mississippi. The facility, commonly known as Beauvoir, was Mississippi’s state home for destitute Confederate veterans and their wives or widows. Two of the men, Frank Childress and Nathan Best, bore clear signs of their wartime injuries. Childress suffered, he reported, from a “sore leg caused by a gunshot wound received during service in 1861.” Nathan Best’s empty sleeve spoke to his injury and amputation during the Petersburg Campaign. None of this made these men exceptional cases among Beauvoir residents except for one key factor. All three men — Childress, Best, and James Burney — had been enslaved Confederate body servants during the Civil War. This had made them eligible for a Mississippi Confederate pension funded by the state, and it also granted them access, or at the very least, consideration for access, to Beauvoir. They were also exceptional as the only African-American pensioners that the Beauvoir Veteran Project research team has been able to find living as residents (not employees) of a Confederate home.

Their admission was the result of an unusual pension policy that began in Mississippi in the late 1880s. When state legislators created the Mississippi’s Confederate pension policy in 1888, it provided modest financial support to Confederate veterans and their widows who had not remarried, as well as “the servants of the officers, soldiers and sailors of the late Confederate States of America, who enlisted from the State of Mississippi.”[1] It was not until the 1920s that five other states passed variations of this policy, joining Mississippi in providing pensions for formerly enslaved Confederate military “servants” or, in other states, laborers. Beyond being early, Mississippi’s policy was unique because legislators decided to pay African-American and white pensioners at the same rate. When Mississippi’s 1890 Constitution omitted reference to pensions for “servants,” state legislators took the time to clarify in 1896 that formerly enslaved men who had served Confederate soldiers could still receive state support. Legislators then took an even more unusual step in the Jim Crow South by insisting that veterans, widows, and “servants” would “share and share alike” from the state’s pension fund.[2]

They did this because in the eyes of white elites, many of whom were former slave owners, it allowed them to aid formerly enslaved men who had served the Confederate military effort in ways that whites saw as acceptable — as camp servants rather than as armed combatants.[3] Indeed, if Mississippi failed to do this, they fed the North’s narrative of the war. As one Mississippi editor explained, if Mississippi ignored such service, it “would mean that while negroes who rendered any military service for the Yankees are handsomely pensioned, those who served their masters in war adopted an evil policy and should be condemned.” Pensions for Confederate “servants” helped sustain the image of “loyal slaves” and similar aspects the Lost Cause memory of the war. [4] This argument swayed leading Mississippians until 1922, when a new generation rejected the idea of equal pensions regardless of race.[5] But this state endorsement was sufficient to warrant Frank Childress, James Burney, and Nathan Best the opportunity to apply for and gain admission as residents of Beauvoir.

In August 1930, a Harrison County pension board reviewed James Burney’s claim that he had served as Confederate President Jefferson Davis’s “

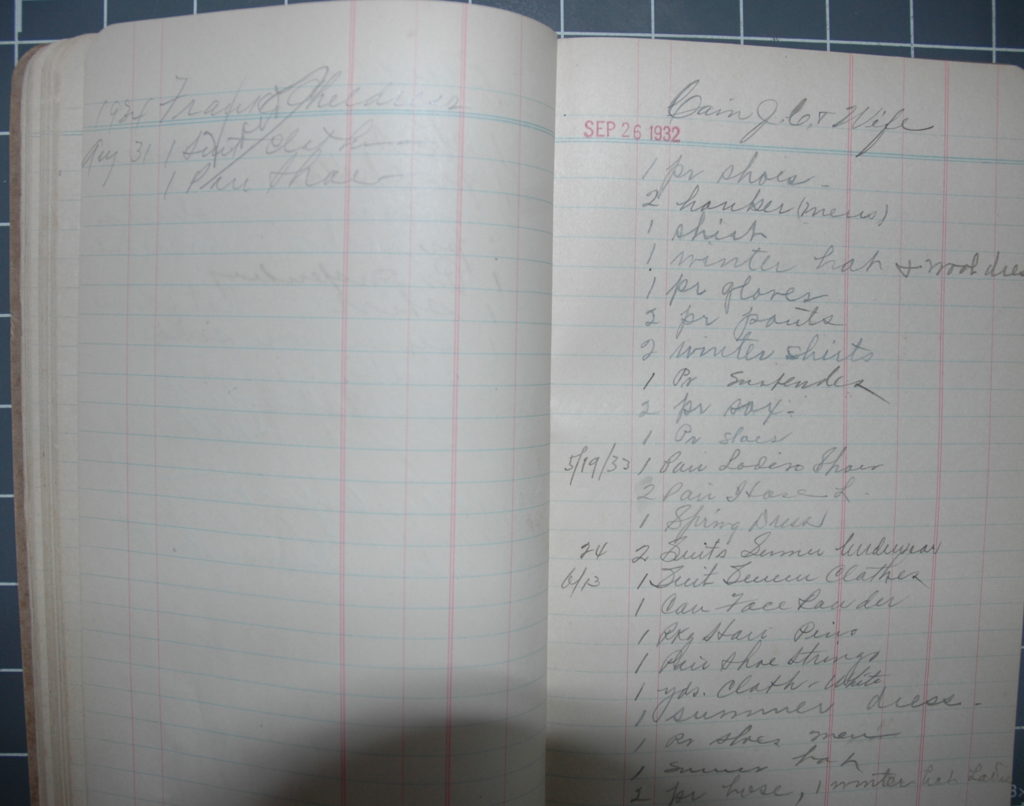

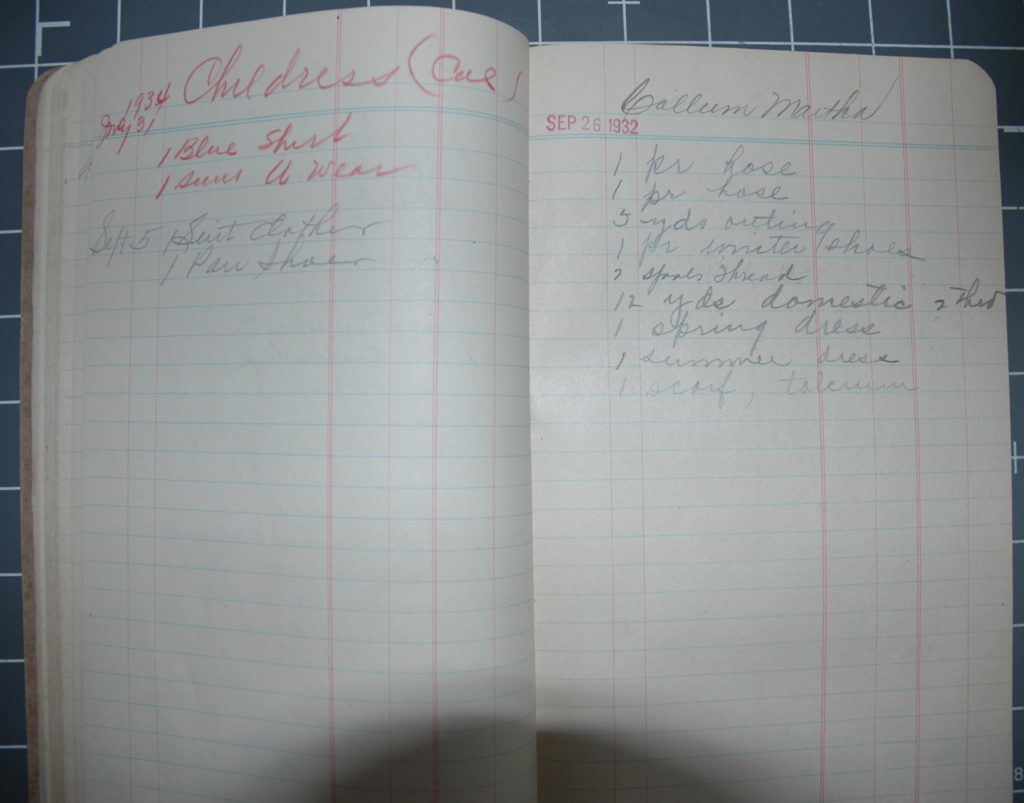

In August 1932, Frank Childress applied for a Confederate pension in Tunica County, Mississippi, where he explained that he had been a body servant to Colonel Mark Childress and suffered an 1861 gunshot wound to his leg. [insert image of Frank Childress pension app] The board approved his application in September 1932, but, like Burney, those funds, reduced on the grounds of race, were not sufficient to sustain Childress. He applied for residency at Beauvoir and arrived at the Jefferson Davis Soldiers’ Home in July 1934. A lack of sources prevents our knowing why Childress moved when he did, but he likely was motivated for the same reasons as many of the residents: at

Much more is known about the third African-American resident of Beauvoir, Nathan Best. [9] He entered the home with James Burney in August 1932, and later lived with Frank Childress. Childress and Best received the same $2 allowance as other residents, but their clothing allotment was less than that of white residents and their cabin was segregated from the cottage-like dormitories that housed white veterans, wives, and widows. Best explained, in the words of a 1930s Works Progress Administrative (WPA) interviewer, how he lived on this meager support: “I

Frank Childress clothing allotment. Beauvoir Ledger “Items Given to Inmates, 1932-1934” Housed at Jefferson Davis Presidential Library, Biloxi, Mississippi.

North Carolina-born Best was about sixteen years old when the Civil War began. He spent his youth enslaved in Snow Hill, North Carolina on the large Greene County plantation of Henry Best.[12] In 1863, Nathan Best went to war with his owner’s younger brother, Rufus Best. While carrying messages during the siege of Petersburg, Nathan Best’s horse fell and Best broke his arm so badly that it needed to be amputated. After the war Best returned to North Carolina where he worked as a farm laborer and married a freedwoman named Hester. He was an engaged voter and active in his community, but this enfranchisement ended abruptly when white North Carolinians “Redeemed” their state and the Klan threatened black North Carolinians who attempted to vote. The years after the war were good, he insisted, until then.[13]

Nathan Best worked in Greene County until 1880, when he and Hester and their three children moved to Wilson County, North Carolina, and then south to Georgia where Best worked in the turpentine industry, as he and his father had before the war. Hester died sometime before 1910, and Best married a woman named Nancy. By then the couple, and perhaps Best’s children, were living in Ocean Springs, Mississippi, a coastal town not far from Beauvoir, where Best made a living plowing small plots of land around town. Although neither could read or write, Nathan and Nancy Best owned their own home and clarified to the census enumerator in 1910 and again 1920 that they owned it mortgage free.[14] By the early 1930s an aging Nathan Best, now in his nineties and a widower — Nancy died in the 1920s — could not earn a sufficient living to sustain himself on a meager monthly pension.[15] He was admitted to Beauvoir and entered the home with James Burney on August 7, 1932.

Nathan Best and Frank Childress were featured in two newspaper and magazine accounts that emphasized their role as Confederate pensioners and residents, and they participated in ceremonies when prominent Americans — like Franklin Delano Roosevelt — visited Beauvoir. Writers highlighted Childress’s capture by Union forces and his admission that he later fought for the Union, but only because, the report claimed, he was forced to do so. A 1936 Mississippi Guide article included what was purported to be a direct quote from Childress himself: “

In a 1930s WPA interview conducted at Beauvoir, Nathan Best gave no indication of such dreams. When he talked about his life as a slave, he characterized his original owner, Henry Best and later his son, Bob, as “good” owners, but Best also described being hanged, whipped, and abused by an overseer on multiple occasions. If Best dreamed of anything in the future, it was leaving Beauvoir. While he liked things “pretty well here,” Best said he “would like it better ifn dey’d jes’ give me ‘nough pension, so I could live at home.”[17] It appears that Best got his wish in March 1939. He received an honorable discharge from Beauvoir and moved to his daughter’s home in Biloxi, and his Confederate pension benefits were reinstated one month later. Best died there in January 1940.[18]

Little

is known about the experiences of African-American residents of Confederate

homes. One scholar has argued that more black pensioners were admitted to

Southern homes as Confederate veterans died and the homes’ white populations

declined. It is not clear, however, that this practice extended beyond

Beauvoir.[19] In

1924, Kentucky’s Confederate home hired William Pete, a formerly enslaved Confederate

body servant, rather than admit him as a resident. The board felt compelled to

do something for Pete, who had been enslaved to Confederate General Joseph

Wheeler, but they refused to admit him as a resident.[20]

Mississippi chose another approach. Nathan Best, James Burney, and Frank Childress

were admitted to Beauvoir and received the same resident allowance, but they

received less clothing and lived in segregated quarters. Even in monthly

payment records and in the Jefferson Davis Soldiers’ Home Register, their names

appear at the back of the old bound volume.[21]

The public wrapped the men in the legend of the Lost Cause and blended their

wartime and postwar experiences into the myth of the happy slave. But James

Burney, Frank Childress, and Nathan Best — despite Klan violence, Jim Crow

bigotry, and reductions in their pensions — used a complicated Confederate

memory to secure shelter at Beauvoir when they had nowhere else to turn. Once there, they challenged residents’ and

visitors’ Confederate memories until Childress and Best’s families could help

them regain their independence with assistance from a Confederate pension.

Notes

[1] Journal of The Senate of the State of Mississippi at a Regular Session Thereof, Convened in the City of Jackson, January 3, 1888. (Jackson, MS: R. H. Henry, 1888), 333.

[2] Laws of the State of Mississippi Passed at Regular Session of the Mississippi Legislature Held in the City of Jackson, Commencing January 7, 1896, and Ending March 24, 1896 (Jackson, MS: Clarion-Ledger Company, 1896), 65; See also Foster, “‘To Mississippi, Alone,’” 34-37; Hollandsworth, Jr., “Looking For Bob,” 305; Dale Kretz, “Pensions and Protest: Former Slaves and the Reconstructed American State,” The Journal of the Civil War Era, 7: 3 (September 2017), 425-445.

[3] Mississippi only awarded pensions to formerly enslaved Confederate body servants. While some applicants referenced carrying dispatches or being wounded in pension applications, the state did not recognize them as combat soldiers. For a detailed analysis of this pension policy, see Hollandsworth “Looking For Bob.” For more on the Black Confederates debate, see Kevin Levin, “Myth of Black Confederates Won’t Go Away,” The Post and Courier (Charleston, South Carolina), October 11, 2017; Levin, “What Black Confederates Really Did During the Civil War” The Atlantic, February 21, 2012.

[4] The Lexington Progress Advertiser quoted in Jackson Daily News (Jackson, Mississippi), February 12, 1904; see a similar argument in Yazoo Herald (Yazoo, Mississippi), February 21, 1908.

[5] House Bill 382, Laws of the State of Mississippi Passed at Regular Session of the Mississippi Legislature Held in the City of Jackson, Commencing January 3, 1922, and Ending April 8, 1922 (Jackson, MS: Clarion-Ledger Company, 1896), 213-215. See examples of protest against this change see Natchez Democrat (Natchez, Mississippi), February 10, 1922 and February 14, 1922.

[6] Hollandsworth, “Looking for Bob,” 310-312.

[7] James Burney Pension Application, September 1, 1930 states that Burney worked for President Davis during the war as a body guard from April 4, 1863 through 1865. There is a letter supporting this claim from Sam Burney, for whom James Burney worked after the war. Burney’s August 1930 pension application makes the same claim. Beauvoir Veteran Project researchers investigated each resident in the sample to verify any reference to military service in the home register or in pension applications. To date no documenting evidence has been found in the Jefferson Davis papers or through inquiries to the National Civil War Museum to confirm or reject Burney’s testimony that he served as Jefferson Davis’s body guard. James Burney Pension Application, Harrison County, Mississippi. Mississippi Office of the State Auditor, Series 1201: Confederate Pension Applications, 1889-1932, Mississippi Department of Archives and History, Jackson, Mississippi; JDSH Register, 360.

[8] Frank Childress Pension Application, Tunica County, Mississippi. Mississippi Office of the State Auditor, Series 1201: Confederate Pension Applications, 1889-1932, Mississippi Department of Archives and History, Jackson, Mississippi; JDSH Register, 360. It is unknown if Childress returned to the care of family or was able to support himself. His daughter, Leloa Smith of Clarksdale, Mississippi, is listed as family in the Beauvoir Register, but the only notation about his departure is that Childress received an honorable discharge on December 28, 1936.

[9] Nathan Best’s name sometimes appears as Nathan Bess. “Bess” appears on one of his pension applications (March 1939), in the Biloxi City Directory in 1931, in the Beauvoir home register, in Beauvoir payroll records, and on the death certificate issued by the state of Mississippi. “Best” appears in his July 1930 pension application, in Harrison County Chancery Court records, in newspaper articles, in a WPA interview, and in correspondence from Beauvoir. I am using “Best” because the use of “Bess” in the home may have started with a misunderstanding or error during Best’s admission which throughout his time at the home and because this is the version of his surname recognized by a descendant and by historians. Special thanks to Jane Shambra, Charles Sullivan, and Deanne Stephens for helping me to unravel this mystery.

[10] Laws of the State of Mississippi Appropriations, General Legislation, and Resolutions Passed at the Regular Session of the Mississippi Legislature … 1932 (Meridian, Mississippi: Interstate Printers, Inc, 1932), 53-54; Laws of the State of Mississippi Appropriations, General Legislation, and Resolutions Passed at the Regular Session of the Mississippi Legislature … 1934 (Jackson, Mississippi: Tucker Printing House, 1934), 17.

[11] “Interview with Frank Childress and Nathan Best,” Folder: Interviews, War Related, Box 10700, Series 447, RG 60: Work Projects Administration, Mississippi Department of Archives and History, Jackson, Mississippi. Very few Beauvoir records exist for the 1930s – Board Meeting Minutes or Biennial Reports would have likely touched on any changes to allowances, but those records from the 1930s have not been found. A ledger listing what each resident was provided between 1930 and 1934 has been located, and verifies that Frank Childress and Nathan Best were provided notably fewer items than white residents. See untitled ledger listing items provided to residents, 1930-1934, Jefferson Davis Presidential Library, Biloxi, Mississippi.

[12] Henry Best died in 1860. His widow, Mariah Best’s, combined real and personal estate in 1860 was $100,000. See 1860 U.S. Federal Census, Tysons Marsh, Greene, North Carolina; Roll: M653_899; Page: 321; Family History Library Film: 803899; 1860 U.S. Federal Census – Slave Schedules. Digitized online, Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2010. Original source: United States of America, Bureau of the Census. Eighth Census of the United States, 1860. Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, 1860. M653, 1,438 rolls.

[13] See Nathan Best in 1870 U.S. Federal Census, Snow Hill, Greene, North Carolina; Roll: M593_1140; Page: 497AB; Family History Library Film: 552639. Rufus Best lists his combined personal and real wealth at $15,000 in the 1870 U.S. Federal Census, Olds, Greene, North Carolina; Roll: M593_1140; Page: 470B; Family History Library Film: 552639. Mariah Best has not been found in the 1870 Census, but by 1880 she was still listed as the head of her household. 1880 U.S. Federal Census, Snow Hill, Greene, North Carolina; Roll: 965; Family History Film: 1254965; Page: 67B; Enumeration District: 065; “Interview with Frank Childress and Nathan Best,” Folder: Interviews, War Related, Box 10700, Series 447, RG 60: Work Projects Administration, Mississippi Department of Archives and History, Jackson, Mississippi.

[14] 1910 U.S. Federal Census, Beat 4, Jackson County, Mississippi; Roll: T624_744; Page: 3A; Enumeration District: 0064; FHL microfilm: 1374757; 1920 U.S. Federal Census, Beat 5, Jackson County, Mississippi; Roll: T625_879; Page: 2B; Enumeration District: 70.

[15] Best’s age listed in the register when he entered the home in 1932 is 90. His death certificate indicates, however, that he was born in 1849, which would have made him 83. JDSH Register, 360. “Residents-Black Inmates” folder, Beauvoir, Soldiers Home Reports, Jefferson Davis Presidential Library, Biloxi, Mississippi.

[16] “Two Colored Veterans at Beauvoir One of Whom Served North as Well,” The Mississippi Guide, November 13, 1936. Transcription in Folder 12, Box 1, “Beauvoir,” Stevens Collection, McCain Archives, University of Southern Mississippi, Hattiesburg, Mississippi.

[17] Nathan Best interview, The Guide, November 13, 1936, Box 128J, Folder: “Racial Groups,” WPA Collection, Mississippi Department of Archives and History.

[18] Nathan Best, Confederate Pension, Form No. 5, Servant, Harrison County, Mississippi. Mississippi Office of the State Auditor, Series 1201: Confederate Pension Applications, 1889-1932, MDAH; Biloxi Daily Herald, January 18, 1940.

[19] Rosenburg, Living Monuments, 136.

[20] Williams, My Confederate Home,242.

[21] JDSH Register, 360.