With the signing of the Treaty of Pontotoc and the cessation of all Chickasaw lands east of the Mississippi River in 1832, thousands of white settlers from the eastern slave states rushed into the fertile prairie belt of northern Mississippi. Among the first families to settle what came to be known as Pontotoc County were Thomas and Caroline Dandridge of Henry County, Virginia. Powhatan Bolling Dandridge was the youngest of their six children and their only son. When he was born in 1839 they named him after Chief Powhatan, their ancestor and the famed father of Pocahontas.

When Thomas Dandridge died in 1842, he had saved enough money to leave each one of his children $440 in land (about $11,116 in 2016). He also left the control of the plantation and eight slaves to his widow, who continued to manage the estate while seeing to her children’s’ education. By 1860, the Dandridge’s land and twenty-four slaves were valued at $32,000 (about $867,715 in 2016).

Powhatan Bolling Dandridge attended the University of Mississippi during the late 1850s before moving on to the Medical College of South Carolina in Charleston (now the Medical University of South Carolina). In 1860, he wrote a thesis investigating malarial fever, earned his MD, and returned to Mississippi to live with his mother and practice medicine.

In 1862, Dr. Dandridge was appointed as the surgeon of the 3rd Mississippi Cavalry, a state militia unit originally organized to serve as minute men. Throughout the winter of 1862 and summer of 1863, the regiment operated locally to counter Union raiding across the Tennessee border. From mid-to-late June 1863, the 3rd Mississippi Cavalry supported the Confederate effort to defend Vicksburg, though they were not captured when the city fell to Union control in July. In August, General James R. Chalmers ordered the regiment to locate and arrest Confederate deserters and conscripts in the state.

After Chalmers was forced to abandon his headquarters in Grenada, Mississippi, the 3rd Mississippi Cavalry and Dr. Dandridge regrouped in Abbeville and attempted to raid William T. Sherman’s supply line in Collierville, Tennessee in October 1863. Although they were able to capture or destroy a significant amount of Union supplies south of Memphis (including General William Tecumseh Sherman’s horse, Dolly), the rebels were ultimately forced to withdraw back to Mississippi. On February 22, 1864, the 3rd Mississippi Cavalry participated in General Nathan Bedford Forrest’s defeat of General Sooy Smith’s expedition at the Battle of Okolana.

On January 6, 1864, General Chalmers (who usually disdained militia units) praised the professionalism and fighting ability of the 3rd Mississippi Cavalry and urged the Confederate Government to enlist the regiment into regular service, which they did. Dr. Dandridge was not among the men who wanted to be folded into the Confederacy’s regular army, however, and he transferred to the 7th Mississippi Cavalry (also known as the 1st Partisan Rangers) instead of accompanying the 3rd Mississippi Cavalry to Georgia in July 1864. Dandridge remained with the 7th Mississippi Cavalry until the end of the war and surrendered at Selma, Alabama on May 4, 1865.

Dandridge began courting Sylvia Lyon, the daughter of a very wealthy planter from Chickasaw County, when he returned home from the war. The pair married in 1866 and had a daughter, Virginia Louise Dandridge, on May 18, 1867. Like many of Mississippi’s former slaveholders, the Dandridges lost an immense amount of wealth after the Civil War. Dr. Dandridge owned real estate in Ellistown, Mississippi valued at just $20 in 1870. He did, however, own $2,000 in personal property, most likely materials associated with his medical practice.

In 1880, Dr. Dandridge had moved his medical practice to nearby Union County, Mississippi. Four years later his daughter married a local farmer named George Lacy Hall and gave birth to a son in 1893. She continued to live in the area until her death in 1939.

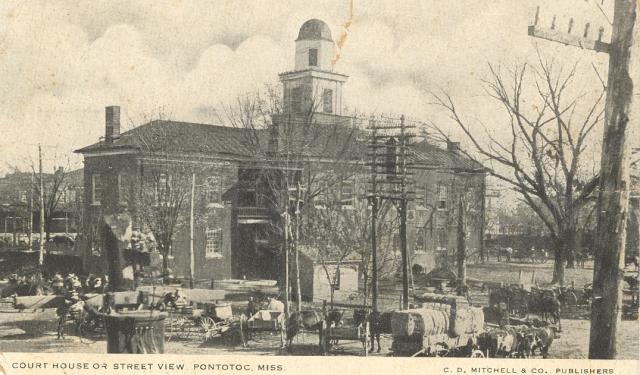

Like many veterans before the widespread use of pensions and social security, Dr. Dandridge struggled to make ends meet as he grew older and less capable of earning an income. His wife, Silvia Dandridge, died sometime after 1880 and by 1900, Dr. Dandridge was reduced to renting a room in the town of Pontotoc.

In 1913, he was granted a small soldier’s pension from the state. By this point Dandridge had moved to Randolph, Mississippi, where he rented a room from his son-in-law. The aging doctor applied for a pension increase two years later when he lost the use of his hands due to rheumatism he claimed to have acquired during the Civil War. In 1916, the Pontotoc County Pension Board granted Dandridge an annual pension of $125 for an irreducible hernia, but the next year the Mississippi State Pension Board reduced it to $75 per annum because it was not related to a wound suffered in combat.

Widowed, impoverished, and incapable of working as a physician, Dandridge was admitted as a resident of the Jefferson Davis Soldiers’ Home at Beauvoir. He lived there among his fellow veterans, their wives, and their widows until the end of his life. Powhatan Bolling Dandridge died at the home on February 13, 1919, and is buried in the Beauvoir Confederate Cemetery.

Lead author: Allan Branstiter, Southern Miss history doctoral candidate. Lead researcher: Robert Farrell, Southern Miss history MA student. Research also conducted by Southern Miss student Danielle Taylor.