C.M. and Charity Coker settled near Summit in Pike County, Mississippi sometime in the 1810s. All eight of their children were born and raised on their modest family farm, including their youngest son Shadrick. Over the course of his seventy-eight years, Shade (as he was called by friends and family) watched Pike County transform from an antebellum backwoods to a New South manufacturing center.

Three of the Coker men served in the Confederate Army during the Civil War. Elder brothers Aleazer and John, enlisted with the 7th Mississippi Infantry in September, 1861. Shade Coker—then seventeen years old—enlisted with Garland’s Battalion of militia cavalry on August 8, 1862, possibly seeking militia service in the hope that this would let him remain home to help with family. Although he enlisted for a three-year term, Shade only remained with his militia unit until April 30, 1863. It is unclear why he left, but it is possible that his brothers may have had something to do with his decision.

On September 14, 1862, Aleazer and John participated in General James R. Chalmers’s poorly planned assault on Union fortifications outside Munfordville, Kentucky. John was struck by a blast of grapeshot and both brothers were captured when Chalmer’s withdrew. They were sent briefly to the Union prison in Cairo, Illinois, before they were exchanged and sent back to the rebel army. Instead, John Coker returned to Pike County without permission. His brother Aleazer returned to the 7th Mississippi Infantry and served with distinction at the Battle of Stone’s River, where his bravery won him a place on the Confederate Roll of Honor—however, he also deserted from the army and returned home by late 1862 or early 1863.

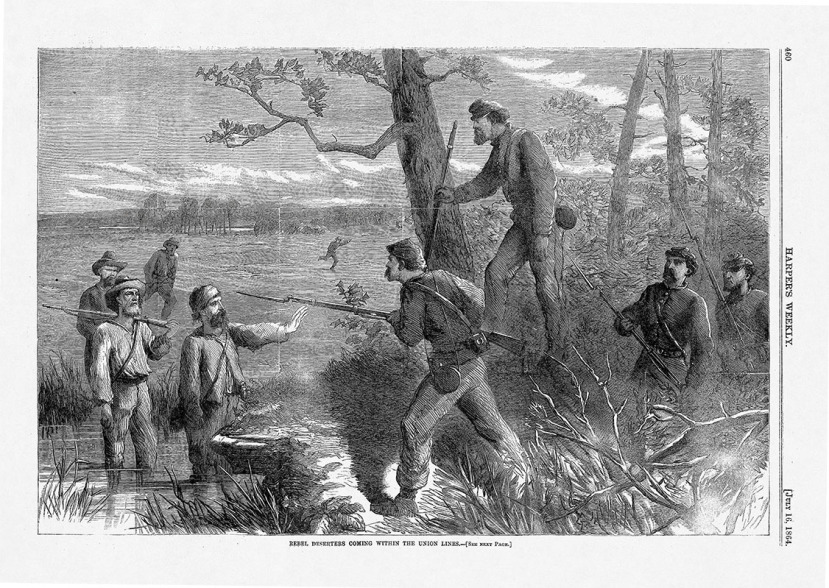

All three of the Coker brothers had abandoned Confederate military service by the time Ulysses S. Grant’s Union army invaded Mississippi during the spring of 1863. Discontent with the Confederate government was growing on the Mississippi home front and hundreds of deserters took to the hills, woods, and swamps. John Coker’s wound was probably reason enough for conscription agents to leave him alone, but Confederate authorities issued a warrant for Aleazer’s arrest during the winter of 1863-1864. Only Shade Coker returned to the army when he served as a teamster from August 1 to September 30, 1864 with the 38th Mississippi Cavalry.

After the war ended, the Coker brothers remained close to home. Sometime before 1870, Shade married a widow name Mary Malinda Collins (née Price) and became a tenant farmer near Brookhaven, Mississippi, where they raised her children and had children of their own. The Cokers would not stay in Brookhaven long, as Shade began looking for opportunities in the burgeoning industrial sector in nearby Wesson.

When the Cokers moved to Wesson it was home to the Mississippi Manufacturing Company (renamed Mississippi Mills in 1873) and a rapidly expanding factory town. The textile mill was built in 1866 by James Madison Wesson and sold to William Oliver and John T. Hardy after it went bankrupt in 1871. After the mill burned down two years later, Hardy convinced Edmund Richardson, one of the richest men in Mississippi, to become a partner and finance the construction of a more modern facility. Richardson soon bought out Hardy and—with Oliver acting as general manager—built four large mill complexes in Wesson between 1873 and 1894.

Life in Wesson was dominated by Mississippi Mills. A strict prohibitionist, James Madison Wesson made sure that the southern border of dry Copiah County jutted far enough south to include his factory. Fueled by the jobs provided by the mill, Wesson’s population skyrocketed from 464 residents in 1870 to 3,168 residents by 1890. Electric lights were installed in the factory in 1882, allowing textile production to continue into the evening. By the 1890s, the mill employed 1,200 workers who produced 4 million yards of cotton goods, 2 million yards of wool, and 320,000 pounds of yarn and twine annually.

Among the people employed at Mississippi Mills in 1880 were Shade Coker and three of his children, Augusta (23), Eugene (18), and Zeno (12). On February 28, 1897, his wife Malinda died and was buried in her parent’s family plot in Bogue Chitto, Louisiana. A year later, Shade Coker married his second wife, Bettie (who was thirty years his junior), and began renting a home apart from his children. In 1900, Shade Coker was still working at the mill, while his children lived in the home owned by his eldest step-daughter, Augusta.

According to the 1910 Census, Shade and Bettie Coker purchased a farm in Brookhaven while his children remained in Wesson. In 1906, Mississippi Mills was forced into receivership having never recovered fully from the death of Edmund Richardson and the Panic of 1893. As a result, only one of the Coker children (Sallie, 39) still worked at the mill, while Augusta took care of the household work and Willie (at 37, the youngest of Shade and Malinda Coker’s children ) sold gum on the street.

Shade and Bettie Coker were fixtures in the social life of their community at the turn of the twentieth century. In 1909, Bettie judged a baby show at the Lincoln County Fair, while Shade became an active figure in local veterans affairs. The Cokers appear to have lost a significant amount of their savings in 1914 when the Commercial Bank and Trust of Brookhaven failed, but they retained control of their dairy farm until at least 1920.

In 1923, Shade and Bettie sold their forty-acre dairy farm and moved into the Jefferson Davis Soldiers’ Home. After a brief stay at Beauvoir, they removed for unknown reasons to Sheffield, Alabama, where Shade died of pneumonia soon thereafter on April 16, 1924. Only 45 year old, Bettie relocated to Hot Springs, Arkansas and finally New Orleans, where she passed away on May 23, 1938. The Brookhaven Country Club now stands on the land once occupied by the Shade Coker farm.

Lead author: Allan Branstiter, Southern Miss history doctoral candidate. Lead researcher: Robert Farrell, Southern Miss MA history student.