Jasper County, Mississippi was organized in 1833 and named after a Revolutionary War hero from South Carolina. Comprised of lands acquired from the Choctaws with the signing of the Treaty of Mount Dexter, the county was settled by families from throughout the South, including H. H. and Martha Anderson. It was there, in the small town of Heidelberg, that their son Volney Anderson was born on April 24, 1848.

The Anderson family owned no slaves, nor did they retain a large plantation or invest heavily in cotton production. Instead, they eked out a living practicing what historian Gavin Wright called “safety-first” farming. A poor yeoman-class family, the Andersons were primarily concerned with protecting their property. Land was the key to their sense of independence and social standing. Consequently, they avoided economic risks and speculating in commodity markets. Unlike the planters of cotton country, the Andersons focused on growing enough food to survive the year and only planted staple crops like cotton or tobacco if they had extra acreage and time. What cash they received in return for their staples on the market was used to buy luxuries and supplies they could not grow themselves.

When the Civil War began, Volney was only thirteen years old. His father attempted to enlist in the 27th Mississippi Infantry Regiment during the winter of 1861, but he was quickly discharged for unknown reasons. Volney enlisted with the 24th Mississippi Infantry under the command of General Edward C. Walthall on his sixteenth birthday, April 24, 1864. When he arrived in near Dalton, Georgia, young Private Anderson was greeted by a body of men hardened by years of difficult service on the battlefields of Perryville, Vicksburg, Murfreesboro, Chickamauga, Lookout Mountain. If Volney Anderson was hoping to prove his mettle in combat, he would soon have his chance.

Breaking camp on May 7, 1864, Anderson and 27th Mississippi marched to an entrenched position defending a hard angle on the left flank of John Bell Hood’s Corps at Resaca, Georgia. A week later, they repulsed two Federal charges and sustained heavy casualties. General Hood reported after the battle, “Walthall’s Brigade suffered severely from an enfilade fire of the enemy’s artillery, himself and men displaying conspicuous valor throughout under very adverse circumstances.”

Volney Anderson’s brigade had less than 500 men in the spring of 1864, and the next few months would be extremely costly of the men. The brigade lost fifty-one men at the Battle of Resaca on May 14; sixteen men at the Battle of New Hope Church on May 17; seventy-eight men at the Battled of Ezra Church on July 28; and forty-two men at the Battle of Jonesboro on August 30-31. According to family history, Anderson was grazed just above his ear by a bullet and survived the disastrous defense of Atlanta physically unscathed.

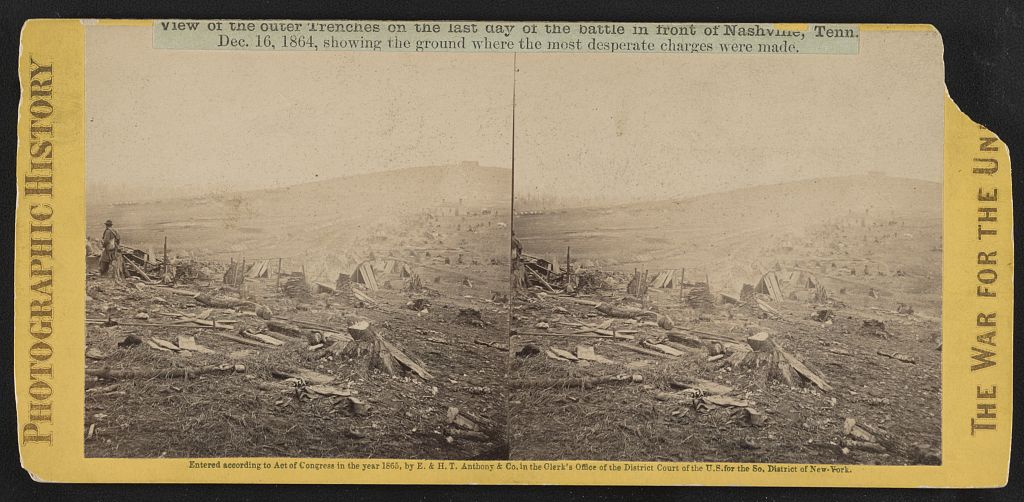

In October 1864, Anderson marched northwards with Hood’s Army and attacked the Union force under Major General John Schofield in Franklin, Tennessee. Hood ordered his men to advance across two miles of open ground (twice as much distance as traversed during Pickett’s Charge at Gettysburg) and attack an entrenched line of Union soldiers. The rebels managed to punch through the first line of Federal defenses, but bogged down when Northern reinforcements arrived. The 27th Mississippi (marching as part of General Stephen D. Lee’s corps) reinforced Hood’s wavering left flank, but the Confederate Army was driven back after sustaining almost 7,000 casualties. Volney Anderson’s brigade lost 76 men killed and 140 wounded. After another costly defeat at the Battle of Nashville, he and what was left of Hood’s Army retreated across the Tennessee River and into Mississippi.

After establishing winter quarters near Tupelo, Anderson and his brigade were granted furloughs until they were ordered to regroup in Meridian on February 14, 1865. Once assembled, Anderson and the remaining 282 men in his brigade made for the Carolinas, where the surrendered with General Joseph Johnston’s army on April 26—two days after Volney Anderson’s seventeenth birthday.

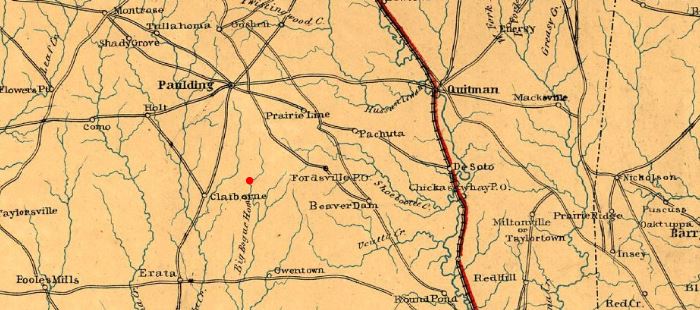

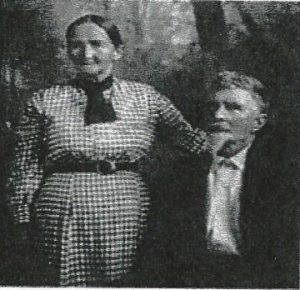

Private Anderson returned to his family’s farm in Heidelberg after the war. On September 3, 1873, he married Nancy McCraney. She was raised in the nearby town of Claiborne by her oldest sister and her husband (Flora and John B. McFarland) after her parents died. Volney and Nancy Anderson had ten children during their 66 year marriage.

In 1881, the Andersons relocated to a burgeoning Pine Belt lumber and railroad hub. Their new town was incorporated and named Hattiesburg, Mississippi the following year. The Andersons were also founding members of First Presbyterian Church. They also sold the timber they grew in plots in nearby Petal and Oak Grove and eventually and became one of the most prominent families in town.

Volney Anderson stopped working sometime after 1910 due to his age. He applied for a Confederate soldier’s pension in 1916 and lived on his farm until he was admitted to the Jefferson Davis Soldiers’ Home in Biloxi on August 9, 1923 (Nancy Anderson was admitted the following October).

They seemed to have enjoyed their time at Beauvoir. Anderson descendants recall Volney enjoying telling guests about his time in the army, and that he once sounded off with a rebel yell when President Franklin D. Roosevelt visited the home in the 1930s. Anderson also told a local paper about a slave who accompanied his company during the war and washed the soldiers’ clothes until an officer “stole” the man. When his grandchildren asked him if he had ever killed a man, Volney stated “I don’t know. But I know that men fell where I was shooting.”

His daughter Bertha, recalls a story her father told about the time he and some men separated from their unit and ran out of food. After traveling a bit and avoiding Union patrols, the starving men came across a farm and stole a goose they found there. Worried that a fire would alert Union patrols of their location, Anderson and his friends snuck into the woods and ate the creature nearly raw. The men inevitably became ill, and Bertha said her father never let his family keep geese on their farm.

The Andersons lived together at Beauvoir until Volney’s death on December 15, 1938 and the age of 91. The funeral was held at First Presbyterian Church in Gulfport, where the pastor read Alfred Lloyd Tennyson’s poem “Crossing of the Bar.” Nancy Anderson died at the home in 1945. Although one of their grandchildren had died in a Japanese prisoner of war camp in the Philippines, the Andersons were survive by ten children, 52 grandchildren, and 42 great-grandchildren. Both Nancy and Volney Anderson are buried at Beauvoir.

Lead author: Allan Branstiter, Southern Miss history doctoral candidate. Research also conducted by Rachael Pace, Southern Miss history student.