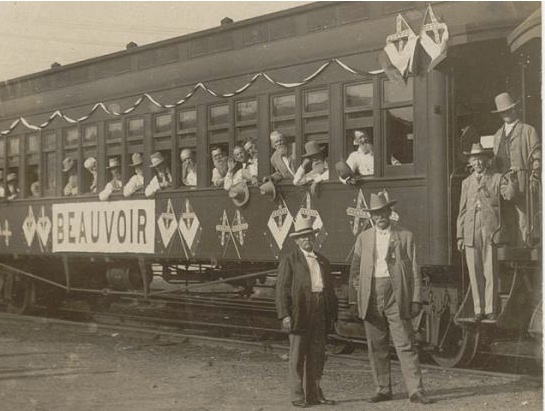

In 1953, Nancy Hawkins Sellers entered the Jefferson Davis Soldier Home in Biloxi, Mississippi, known more famously as “Beauvoir.” It was created to care for impoverished Confederate veterans, as well as their wives and widows, who had been approved for military pensions. Oddly enough, Nancy Sellers had no direct memory of the American Civil War. Born in 1867, she was the eldest of seven children raised in the Florida panhandle where her father and grandfather worked as laborers with no noted property or personal wealth when the war began. In the 1880s, though, Nancy met John Andrew Sellers, whose prewar life was the exact opposite of hers.

Raised on a farm in Jones County, Mississippi, John Andrew Sellers was about 26 years old when the war began with an estate valued at $1000 and estimated his personal wealth estimated at $15,000, likely tied to the eight slaves he or his father (also named John) owned. The elder John Sellers’s estate was even larger, valued at $15,000 with a personal wealth close to that of his son’s. Sellers joined the “Rosin Heels” in August 1861 “for the war” and mustered into Confederate service as a private in Company B, 27thMississippi Volunteer Infantry Regiment. Captured at Lookout Mountain in November 1863, Sellers was sent to the Union prisoner of war camp at Rock Island, Illinois. He remained in captivity for the next year and a half until he was paroled in the spring of 1865.

The Sellers’ postwar world differed drastically from the life they had known. In 1870, John Andrew Sellers was farming again, but his estate had dwindled to $220 with a personal wealth of $660. His father had been similarly reduced and noted nearly the same wealth to the census taker, and things do not appear to have improved by 1880, which found John and his first wife, Mary Easterling, still farming in Jones County with nine children and one on the way. Mary died in 1881 and John remarried five years later to Lydia Bynum, but she died a year later in June 1887. A year after that was when John, then 54, married Nancy Hawkins, just 20 years old.

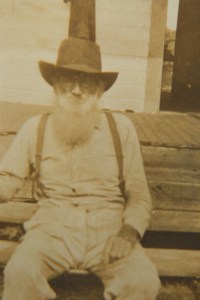

John and Nancy Hawkins Sellers had eight children of their own amid the poverty that continued to plague them. When he finally applied for a Confederate pension in 1917, Sellers listed himself as a farmer with the same wealth he had claimed almost fifty years earlier. Ironically, he never lived at Beauvoir. Sellers died in 1922 in Forrest County, Mississippi, where he and Nancy lived with five of their children. But his Confederate pension made it possible for Nancy to enter the home, though she waited until 1953. It could be that her grandchildren — she was living with three of them, listed as the head of household, in 1940 in Hattiesburg, Mississippi — could no longer care for her, but the exact cause for the move is unknown. And her stay was brief. In early 1953, Nancy Sellers entered the Beauvoir home, but she received an honorable discharge at the end of May that year, and died that August back home with her family in Hattiesburg.

The post-Civil War South is remembered for its social, political, and economic chaos and the rise of the Ku Klux Klan. It is studied as an age of great possibility as enslaved peoples embraced their hard-won freedom, and it is popularly remembered for Tara-like plantations crumbling amid broken fortunes and dark futures.

Rarely mentioned, though, are those Southerners like John and Nancy Sellers who lacked the postwar security to preserve and publish their wartime writings, assuming these veterans and their families were sufficiently literate to have written during the war. In John Andrew Sellers’s case, he was certainly literate. But that is not true of many of the Beauvoir residents. And even in Sellers’s case, we have found no record of wartime letters or other papers to help us learn more about this family.

With the majority of our Civil War soldier studies based on wartime and postwar correspondence and publications, we have a gaping hole in our knowledge when it comes to those impoverished Southerners who entered Confederate homes from Richmond to Austin in the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries. Due to the limited record keeping at places like Beauvoir and modern privacy laws that hinder historians’ ability to access what papers do exist, we know very little about veterans’ lives within the homes. Existing studies of institutions like Beauvoir indicate that those who lived there were known as inmates, not residents, and they often complained of the controlling habits of their administrators and governing boards. Homes served as monuments to the Lost Cause where residents became caricatures of “old times … not forgotten.” Indeed, historians of the Civil War veteran experience have argued persuasively that our understanding of these men and their families have been shaped more by what the public — then and in subsequent generations — chose to preserve, share, and remember than any true sense of who these men and women where and what their postwar lives were like.

In the fall of 2014, my colleague, Deanne Nuwer, and I launched “The Beauvoir Veteran Project” (BVP) at the University of Southern Mississippi. The BVP seeks to cut through the mists of memory to understand the lives and experiences of the veterans, wives and widows who found themselves at the Jefferson Davis Soldier Home — Beauvoir in Biloxi, Mississippi, between 1903 and 1957. Of course, the challenges in studying impoverished and largely illiterate people remain; we have found no new sources. But modern digitization efforts make it easier than ever to learn about the men and women who spent their latter-most years at Beauvoir. We have had particular success with the census records of 1850, 1860, and 1870, as well as the slave schedules, which allow us to map the trajectory of veterans’ socio-economic lives before and after the war. Compiled service and pension records offer insights into their experiences in uniform thanks to notes on wounds, imprisonment, hospitalization, desertion, promotions and demotions, as well as their economic status late in life. Finally, nineteenth-century newspapers reveal how these men and women were seem by their communities. All of these recently digitized records allow us to paint a far more detailed and accurate image of the men and women who have remained largely in the shadows of the Civil War era.

Utilizing the same methods that led to the creation of my statistical sample of the over 7000 men who served in the Texas Brigade, Deanne and I created a sample of the approximately 1850 men and women who lived at Beauvoir in the first half of the twentieth century. We’ll be launching the BVP website next month, where visitors can read about some of the findings that our undergraduate and graduate researchers have been working on since August. You can also check us out online to learn about Beauvoir residents who still need to be researched and how volunteers can contribute to the BVP. We’ll announce the Beauvoir Veteran Project via my personal page on Facebook, as well as on the Dale Center’s Facebook page, so please stay tuned to learn more.

* Special thanks for their key role in our research on Beauvoir are due to Jane and Charles Sullivan, PRCC, as well as USM student JoAnna Gunnufsen for her research on the Sellers.

X-post from the Dale Center for War & Society’s blog “Reflections on War & Society” by Dr. Susannah Ural.

Susannah Ural, Ph.D., is Co-Director of the Dale Center for the Study of War & Society at Southern Miss and is the author of Don’t Hurry Me Down to Hades: The Civil War in the Words of Those Who Lived It (Osprey, 2013) and The Harp and the Eagle: Irish-American Volunteers and the Union Army, 1861-1865 (NYU Press, 2006). Her current project, Hood’s Boys: The Soldiers and Families of Hood’s Texas Brigade, will be published in 2015 by LSU Press.