Secessionism swept over Mississippi like a fever after the election of Abraham Lincoln to the White House, and Neshoba County was no exception. Charles A. Nash’s father, Ira Sr., strongly opposed secession despite the fact that he was a born-and-bred Southerner and wealthy slaveholder. The elder Nash had been a prominent leader in the county during the antebellum years, and he served in the state legislature in 1846. When Mississippi called for a secession convention in 1860, Ira Sr. ran as a Unionist and was soundly defeated by a margin of 601 to 58 votes. Unable to stop the “irrepressible conflict,” he watched his sons donned Confederate gray in nearby town of Philadelphia, and marched off to fight for the Confederacy with the 5th Mississippi Volunteer Infantry Regiment.

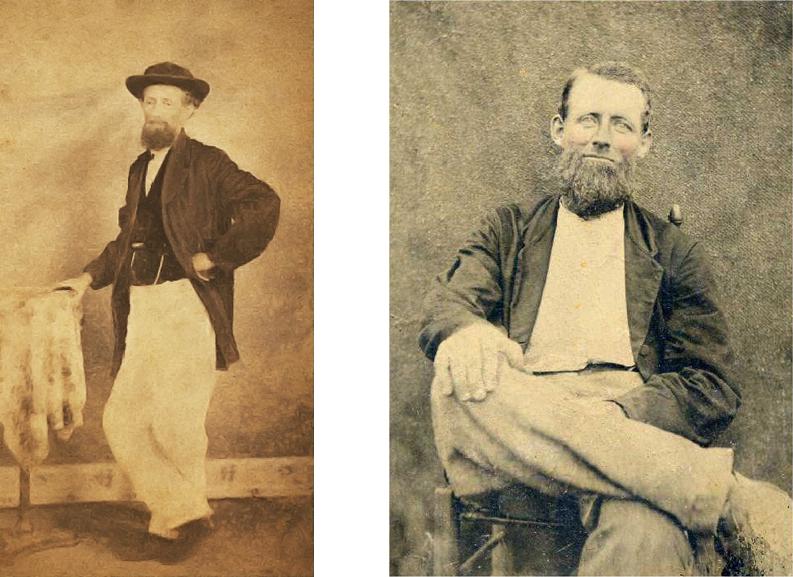

The youngest of Ira Nash, Sr.’s boys, Ira Jr., was 18, still unmarried, and living at home when he enlisted, but the older sons, John and Charles, 30 and 29 respectively, left behind young families when they joined the Confederate Army. This included Charles’s wife Eliza, who remained at home raising two young daughters and an infant son.

In February 1862, Union forces under Ulysses S. Grant captured the Fort Henry and Fort Donelson in Tennessee, which forced Confederate General Albert Sidney Johnston’s forces to retreat southward and leave the Tennessee and Cumberland rivers in Yankee hands. For decades, southern planters had relied on these great waterways to send their crops to distant markets and their loss left the heart of the Deep South exposed to economic peril and large-scale invasions from the north. To counter this threat, the 5th Mississippi was transferred home in early 1862 and assigned to General James Chalmers’s Brigade in Johnston’s newly organized Army of the Mississippi. Gathering near Corinth, Mississippi, the Nash boys joined some 55,000 men hoping to stop Federal forces from capturing the city’s important rail-head.

On April 3, 1862, General Johnston moved his army—including the 5th Mississippi— quietly across the border and into Tennessee, where he hoped to catch the Yankees in camp with their forces divided. Although he planned to attack Grant on April 4, Johnston lost two days due to torrential rains that turned roads to mud and soaked his men’s gunpowder. His subordinate, Confederate General P.G.T. Beauregard, feared the initiative was lost when men started firing their muskets to test their powder (and possibly revealing their position to the enemy), and worried about the Union army’s possible numerical superiority. Beauregard urged Johnston to abort the assault and withdraw back to Corinth, but Johnston refused and declared that “I would fight them if they were a million.”

Despite Beauregard’s concerns, the Confederates had the advantage when the battle of Shiloh began on the morning of April 6, 1862. Federal commander Ulysses S. Grant had hoped to avoid any engagement until reinforcements arrived that would guarantee him a numerical advantage. Convinced rebels were preparing for a siege back in Corinth and hoping to avoid any interaction with Confederate patrols that would spark a fight, Grant did not order his men to build defensive entrenchments or deploy pickets to protect his camps. At about 5 a.m. a Union patrol encountered and engaged a force of Confederates in the woods south of Grant’s position, but no alarms were raised. A few hours later, as Union soldiers were preparing breakfast, startled deer burst forth from the wood line with the bulk of the Confederate infantry in hot pursuit. By 9 a.m. rebels were assaulting Union regiments all along the length of Grant’s line.

Albert Sidney Johnston’s battle plan was simple. He assigned each of his corps commanders a sector, with Leonidas Polk on the Confederate left and William J. Hardee on the right, Braxton Bragg in the center, and John Breckinridge in reserve. By strengthening his right flank with Breckinridge’s reserve corps, Johnston hoped to cut off the Yankee’s escape route and supply line on the Tennessee River. It was there, on the extreme right of the Confederate Army, where Chalmers’s brigade was located, including the 5th Mississippi and John and Ira Nash. Charles (as chance would have it) was not with his brothers at Shiloh, having returned home on leave a few weeks earlier to help his father with the family church. Moving forward across deep ravines, dense undergrowth, and muddy streams, Chalmer’s men (supported by artillery) attacked a startled Union brigade under the command of Colonel David Stuart at 7:30 a.m.

Stuart’s men held their position behind the lip of a steep ravine for over an hour until Chalmers’s men successfully punched a hole in the Union line. Under immense pressure from the rebel charge, Federals withdrew to a hill about 150 yards to their rear. Chalmers continued to advance, encountering four companies of Zouave skirmishers. They “secretly advanced close to our left,” Chalmers reported, and “fired upon the Fifty-second Tennessee regiment, which broke and fled in most shameful confusion.” Elements of the 52nd quickly regrouped and joined the ranks of the 5th Mississippi.

By the time Stuart got his brigade set in their new positions, he realized that his 800 men were now cut off from the rest of the army. On high ground protected by a fence and a stream, Stuart was determined to hold his position. Chalmers’s men deployed skirmishers and began to advance through an orchard in, according to their commander, “almost perfect order and splendid style.” Federals waited until Confederates came within about 40 yards of their line before unleashing a hellish volley that tore through the rebel line. It was in this engagement, at about 9:00 a.m., that Union gunfire struck Sgt. Ira Nash, Jr. in the forehead, killing him instantly. Nearby another bullet struck John Nash in the thigh. Chalmers reported that his men then surged forward and “after a hard fight drove the enemy from his concealment, though we suffered heavily in killed and wounded.” He later commended the 5th Mississippi and their commander, Colonel A. E. Fant, stating that “all the Mississippians, both officers and men, with a few exceptions . . . behaved well.”

The Battle of Shiloh devastated the Nash family. Ira, Jr., had been killed and John was in a hospital trying to survive a flesh wound that refused to heal. Later in July, their Unionist father appeared at the probate court in Philadelphia to collect the pay and bounties the Confederate government owed his dead son. In time, John would return home with a limp while Charles remained with the 5th Mississippi only until September 1862. Soon thereafter, Charles and Eliza welcomed a new son into the world and named him Ira Marion Nash II after their slain brother. While Charles later claimed that he was discharged due to a physical disability, his brother’s sacrifice may have also helped his commanders justify his discharge. It is also entirely possible that Charles had been sent home prior to Shiloh because of a physical disability.

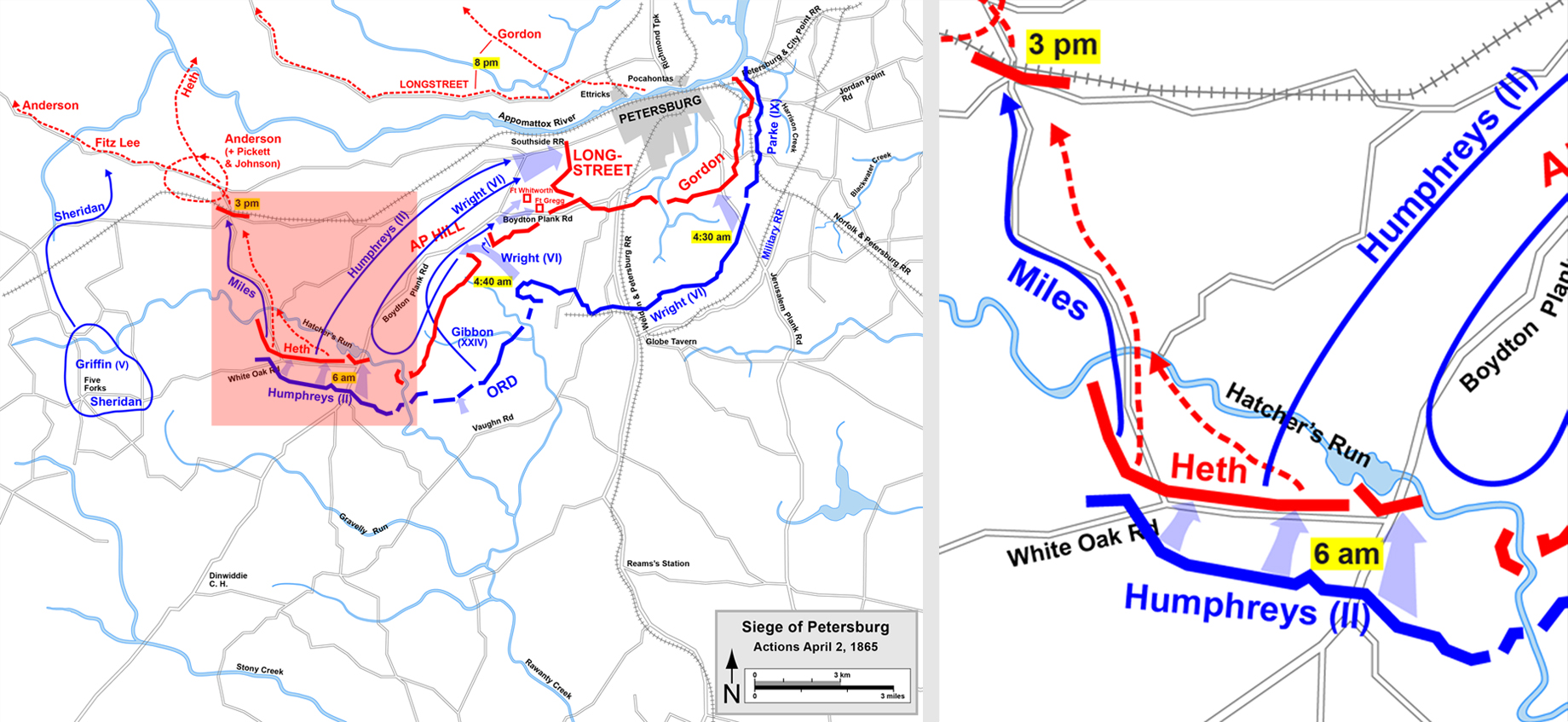

Charles Nash’s Civil War did not end in 1862. On November 21, 1864, he returned to military service by joining Co. D of the 11th Mississippi in General Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia. The 11th Mississippi was a hard-fighting combat unit that had participated in most of the major battles of the Eastern Theatre. By the spring of 1865, this once hale group of young men—drawn from lecture halls of the University of Mississippi and the cotton aristocracy—had been reduced to only 64 men commanded by Lt. Colonel George Shannon. When Charles Nash arrived in Virginia just before the Confederacy’s final spring, his new unit occupied the trenches southwest of Petersburg, Virginia, as part of General Henry Heth’s division.

On April 2, 1865, General Grant launched a large-scale attack against the rebel earthworks. Although the 11th Mississippi held their position, the thin line around them fractured under immense pressure from the Federal attack. General Heth ordered his men to retreat north, but the 11th was trapped by Hatcher’s Run, a wide stream swollen by recent rains, making it impossible to ford. A few of the men attempted to swim across and escape under a hail of rifle fire, but most of them surrendered. By nightfall, Richmond was abandoned and in the hands of Union soldiers, while what remained of the Confederate army retreated towards Appomattox Court House. In poor health after years of hard campaigning and months of siege combat, General Lee’s army laid down their arms on April 9, 1865. Having surrendered at Hatcher’s Run, the 11th remained in a prisoner of war camp in Point Lookout, Maryland, until they took the Oath of Allegiance to the Union en masse on June 29, 1865. Only then could they return to Mississippi.

After the collapse of the Confederacy, Charles Nash found work as a carpenter. While he would never match the wealth of his father, Charles seems to have found consistent employment building rail cars for the region’s expanding network of railroads. Every census between 1870 and 1910 shows Eliza and Charles living in a new place: Clarke County in 1870, Lafayette County in 1880, Washington County in 1890, with Ira II’s family in Colbert County Alabama in 1900, and finally at the Jefferson Davis Soldier Home at Beauvoir in 1910. No matter where he went, Charles relied on his skill as a carpenter to provide for his family, and he continued in this line of work into his late 60s.

After half a century together, Eliza passed away and Charles began to apply for a veteran’s pension in 1907. His mind and vision were clouded by the years, and he had difficulty recalling the details of his Civil War service. Embarrassed by his inability to answer the state’s questions, he scribbled an apology at bottom of his application: “I have forgotten some of the answers, my mind is not good, I can’t remember.” Regardless, the state had enough to verify that he had served honorably and was financially destitute. Charles Nash became a resident of Beauvoir three days before Christmas in 1909.

He seems to have enjoyed his life at the home, and Charles Nash was an active participant in the community’s social life. He participated in veterans’ reunions and donated $35 to a “Memorial to Women of the Confederacy” in Gulfport—an impressive sum considering the small amount of money he received as a pension. Charles Nash lived the rest of his life out on the shores of the Gulf of Mexico with his fellow comrades-at-arms. On August 11, 1913, just around supper, he passed away at the age of 83 years old, leaving “two sons and two daughters and many grandchildren to mourn his loss.” He was buried the next day in Beauvoir’s cemetery.

Special thanks to Mr. Len E. Reinker, a direct descendant of John J. N. Nash, for providing the BVP with information on the Nash family of Neshoba County. Please visit his website. Thanks, too, to BVP team members for their research on Charles Nash and family. Lead author: Allan Branstiter, Southern Miss history doctoral candidate. Lead researcher: Southern Miss History major Armendia Hulsey. Research also conducted by Southern Miss History major Hannah Smith.