When Stephen Cocke Moore was born in 1836 in Monroe County, Mississippi, the nearby town of Aberdeen was little more than an unincorporated settlement on the banks of the Tombigbee River. His parents, Lucien and Rebecca of Tennessee, were among the first white pioneers to settle the area during the land rush that followed the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek in 1830. The area would change dramatically over the course of Stephen’s early life, as the intertwining of capitalism and slavery carved out small cotton kingdoms for some and immense losses for others.

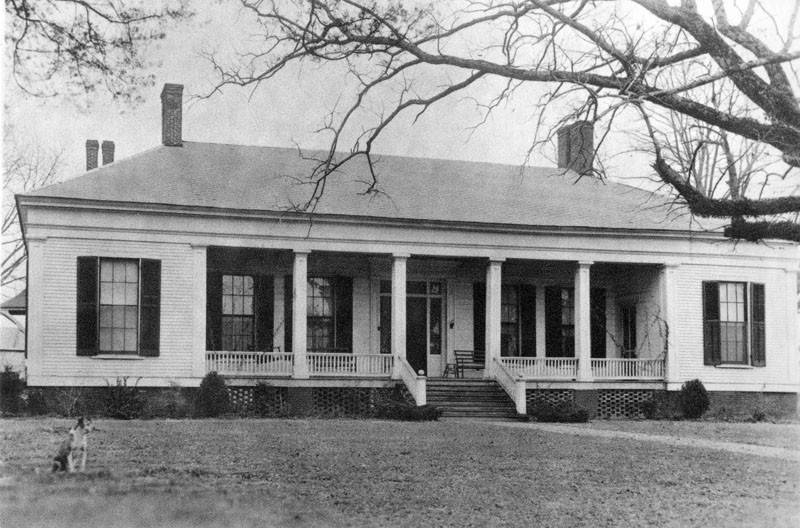

Stephen’s family navigated the boom-and-bust cycle of the cotton economy better than most, and his family’s wealth increased from $1,000 to $78,000 between during the 1850s. The Moore’s decorated their home with European furniture imported purchased from shops in Aberdeen’s extravagant Commerce Street and “Silk Stocking Avenue” (Franklin Street), like their wealthy neighbors who lived in the mansion and plantations that dotted Monroe County. While his older brother James had taken up cotton cultivation like their father, Stephen became an attorney in Aberdeen. Like many of Mississippi’s patricians, the Moore’s comfortable lives were built on the back of the forty-seven African-American men, women, and children they held in bondage.

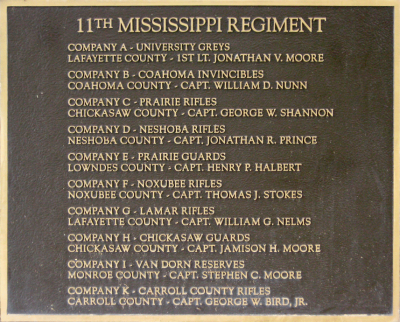

Considering their place among the cotton empire’s slaveholding elite, it should not come as a surprise to learn that the all three of the Moore brothers volunteered to fight on behalf of the Confederacy less than two weeks after the fall of Fort Sumter. James (26), Stephen (23), and Lucien Jr. (21) enlisted together as privates in Company I of the 11th Mississippi Volunteer Infantry Regiment on April 27, 1861. Like most of the men of their regiment—notably the University of Mississippi students who comprised much of Company A (“University Grays”) and Company G (“Lamar Rifles”)—the Moore brothers were much more affluent and better educated than the average Confederate soldier.

The men of 11th Mississippi were quickly transferred north and mustered into service in Lynchburg, Virginia, as part of General Joseph E. Johnston’s Army of the Shenandoah. The regiment was sent by train from Winchester, Virginia, to reinforce General P. G. T. Beauregard’s command during the First Battle of Manassas on July 21, 1861, but arrived too late to see combat. James Moore returned home to Monroe County shortly afterwards and enlisted in the 43rd Mississippi Infantry, while Stephen and Lucien Jr. remained with the 11th Mississippi and spent a miserable winter encamped near Dumfries, Virginia.

Less than a hundred miles north of the Moore plantation, Confederates under Generals Albert Sidney Johnston and Beauregard launched an attack against General Ulysses S. Grant’s army in the woods around Pittsburg Landing, Tennessee. Over the course of the next forty-eight hours over 23,000 soldiers were killed, wounded, captured, or went missing during the Battle of Shiloh. The bloodiest battle on American soil up to that point, Shiloh’s carnage shocked the divided nation and disproved predictions that secession would be a short and bloodless revolution. Like most Confederate regiments, the 11th Mississippi reenlisted for the duration of the war and held elections for officers after the Battle of Shiloh. In May 1862 the men of the regiment elected a new commander (the popular Colonel Philip Liddell), while Company I chose Stephen Moore to serve as a 1st Lieutenant.

It would not be long before Lt. Moore and his men would have their first real taste of combat. Less than month after Moore was commissioned, the 11th Mississippi was actively engaged in battle during the Peninsula Campaign. At the Battle of Seven Pines on May 31, 1862, the regiment’s 504 men charged an advancing line of Federal infantry during a poorly organized attempt to protect the Confederate Army’s left flank. Raked by musket and cannon fire, the regiment lost twenty killed and one hundred wounded. Among the day’s casualties was Lucien, Jr., who lost an arm and was evacuated to Chimborazo Hospital in Richmond.

After Seven Pines the army’s new commander, General Robert E. Lee, reassigned them to General “Stonewall” Jackson’s force in the Shenandoah Valley as part of a diversionary movement. Once the regiment arrived in the valley, they promptly turned around and marched secretly back to Lee’s position and attacked the Union General George B. McClellan’s right flank during the Battle of Gaines’s Mill.

Just after noon on June 27, 1862, General Lee launched a frontal attack against an elevated Union line protected behind entrenchments, trees, creeks, and swampy ground near Gaines’s Mill. Confederate losses mounted after repeated attacks faltered in the face of withering fire from the Yankee lines. General A. P. Hill’s division lost over a quarter of its men, and Lee himself joined in on the attack and urged his men to advance. Meanwhile, Jackson’s column (including Moore and his comrades) was delayed by poor directions and sniper fire as it slowly worked its way to the front. They arrived late in the day, weary after a day’s march, and prepared for another attack.

The four hundred men of the 11th Mississippi was part of Evander M. Law’s brigade when General Lee launched a massive attack along the entirety of the Union line at 7 o’clock that evening. Working in tandem with Hood’s Texas Brigade on its left, Law’s Brigade moved quickly and broke through the Union center. Exhausted and low on ammunition, the Union soldiers withdrew across the Chickahominy River and burned the bridges behind them. The 11th Mississippi suffered over 150 casualties—a loss of almost forty percent of its total strength—and did not see major action again for the rest of the campaign.

After General McClellan’s Army of the Potomac withdrew to Washington, DC, Lee sent Stonewall Jackson’s force north to intercept General John Pope’s Army of Virginia as it moved south against Richmond. Jackson deftly maneuvered his way behind the Union army and took a defensive position behind near Manassas on August 27, 1862. For his part, Pope believed he had caught the rebel army divided and launched an attack against Jackson on August 28. Often remembered for his offensive prowess, Jackson skillfully held back Pope’s forces for two days while Longstreet’s wing conducted a forced march to relieve his beleaguered soldiers.

Longstreet and the 11th Mississippi arrived on the field late during the second day of the Battle of Second Manassas and launched an attack against the Federal army’s flank the following day. Longstreet’s ability to control his corps was hindered as his men moved quickly over difficult terrain. As command and control broke down, the attack’s success would rely greatly upon the command initiative of brigade and regimental commanders as they proceeded forward. This was the case with the 11th Mississippi, which became separated from the rest of its brigade while it advanced across two miles of rugged woods, creeks, and ridges. Despite these challenges, the men of the 11th stayed together and performed well under the command of Colonel Liddell and officers like Lt. Moore. Longstreet’s assault ultimately stalled at dusk, but it was enough to convince Pope to withdraw his army from the field.

After the Battle of Second Manassas, General Lee marched his victorious army across the Potomac into Maryland as the Union armies regrouped under General McClellan in Washington. When McClellan intercepted papers indicating that Lee’s army would be temporarily divided while Jackson moved to seize Harper’s Ferry, he moved aggressively against Lee’s men near Sharpsburg, Maryland. During the night of September 16, 1862, the Federal army shelled the rebel line and mortally wounded Colonel Liddell. As the sun rose on what would become the bloodiest day on American soil, the 11th Mississippi would be without its beloved commander.

At about 5:30 a.m. on September 17, 1862, General Joseph Hooker’s Union corps attacked Stonewall Jackson’s men in a cornfield north of Sharpsburg. After a viciously fought stalemate that devolved into fierce hand-to-hand combat, the 11th Mississippi (now part of Hood’s Division) was ordered to counterattack through the West Woods near the Dunkard Church. Once in the cornfield, they engaged Union forces under General John Gibbon, which included the famously tenacious Iron Brigade. After losing half of their men as well as their battle flag, the 11th Mississippi retreated from the battlefield. When asked where his division was, Hood replied “Dead on the field.” Somehow, Lt. Moore emerged unscathed.

Constant campaigning and high combat losses took a heavy toll on the men of the 11th Mississippi. In November 1862, they were sent to Richmond and reorganized as part of a new brigade commanded by Jefferson Davis’s nephew, Joseph R. Davis. Major Francis M. Green of Oxford, Mississippi, was also appointed the regiment’s new commander and spent the winter of 1862-1863 recruiting new soldiers to fill out his unit.

The 11th Mississippi joined General Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia during the Gettysburg campaign, crossing the Potomac once again on June 25, 1863. Now promoted to Captain, Stephen Moore commanded Company I on July 3 when his regiment joined Pickett and Pettigrew’s assault on Cemetery Ridge during the Battle of Gettysburg. The 11th Mississippi briefly penetrated the Union line, but was repulsed after incurring 336 casualties (or eighty-seven percent of their men). Only forty of the regiment’s men emerged from the battle unscathed, while every soldier of Company A was wounded or killed. Captain Moore was wounded in the knee by an artillery shell during the attack, and eventually made his way back to Mississippi to recuperate.

Moore officially tendered his resignation as an officer in the 11th Mississippi on February 13, 1864. It is difficult to uncover Moore’s activities during the final year of the Civil War. A few days after he left the Army, Moore was apparently captured by Union soldiers back home in Aberdeen. However, on May 9, 1864, a letter states that rumors that the wounded captain was “resigned & disabled” were untrue, and that he was actively raising a new company of soldiers for the Confederate Army. While Moore’s service records ends in May 1864, he later testified that he surrendered in 1865 to the U.S. Army in Scooba, Mississippi—a fact that would place him among the few state militia soldiers remaining in rebellion during the final days of the Civil War.

Despite his wound, Moore remained active during Reconstruction. After returning to his parents’ home, he busied himself with managing the plantation alongside his mother. In October 1865, he attempted to raise a local militia company with Lucien J. Morgan (which is odd because records indicate the latter had been killed at Gettysburg). Despite the emancipation of their former slaves, the Moores remained as one of the wealthiest families in Monroe County according to the 1870 Federal Census.

Stephen never married. By 1880, he was 44 years old, apparently unemployed, and living with his brother James’s family. The 1900 Census lists him as a property lien clerk boarding with George and Zelda Bean of Okolona, Mississippi. When he eventually applied for a Confederate military pension, he was living on veteran’s land in Vicksburg and had no surviving relatives besides James’s daughters—Mary Green, Carrie Gillespie, and Margaret Fulton. Stephen Moore was awarded a pension on September 8, 1902, and moved to Beauvoir on December 2, 1905. He was remembered in his obituary as a man whose “brilliant mind and extensive reading . . . fund of natural wit, and wealth of anecdote and reminiscence, made him a rare companion.”

Lead author: Allan Branstiter, Southern Miss history doctoral candidate. Lead researcher: Southern Miss History major Armendia Hulsey. Research also conducted by Southern Miss student Kayla Sims.